USA Today Bestselling Romance Author

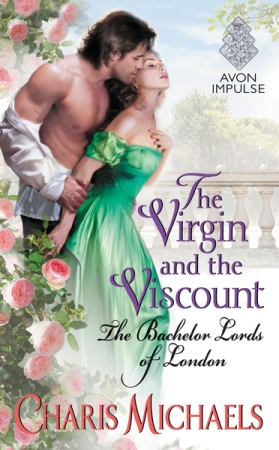

The Virgin and the Viscount

Book 2 of the Bachelor Lords of London Series

THE VIRGIN

Lady Elisabeth Hamilton-Baythes has a painful secret. At fifteen, she was abducted by highwaymen and sold to a brothel. But two days later, she was rescued by a young lord, a man she’s never forgotten. Now, she’s devoted herself to save other innocents from a similar fate.

THE VISCOUNT

Bryson Courtland, Viscount Rainsleigh never breaks the rules. Well, once, but that was a long time ago. He’s finally escaped his unhappy past to become one of the wealthiest nobleman in Britain. The last thing he needs to complete his ideal life? A perfectly proper wife.

THE UNRAVELING

When Bryson meets Elisabeth, he sees only a flawless candidate for his future wife. But a distant memory calls to him every time he’s with her. Elisabeth knows she’s not the wife Bryson needs, and he is the only person who has the power to reveal her secret. But neither of them can resist the devastating pull of attraction and as the truth comes to life, they must discover that an improper love is the truest of all.

Connected Books

The Virgin and the Viscount

Book 2 of the Bachelor Lords of London Series

The full series reading order is as follows:

- Book 1: The Earl Next Door

- Book 2: The Virgin and the Viscount

- Book 3: One for the Rogue

Author's Notes

The Virgin and the Viscount

Buy your copy →

What’s the Deal with All the Virgins?

I once had a note from an editor in the margin of a manuscript: “Can we ease up on the virgin worship? It’s like he has a virgin fetish?”

I had to laugh—first because what other profession invokes this kind of note, but also because if anyone has a virgin fetish, I guess it’s me. Virgins are my strong preference as a reader and writer. We are dealing in fantasy here, and it’s simply part of mine. I acknowledge fully that not everyone shares this fantasy. Certainly, virginal heroines are not as thick on the ground as they were when I read Judith McNaught’s Almost Heaven, my first romance, back in 1989. In today’s contemporary romance, I’d venture to say that virgins are almost nonexistent.

However, when my editor rejected the working title for Elisabeth and Bryson’s book, I offered up The Virgin and the Viscount as an alternative and she leapt at it. V&V remains my best seller to date. So perhaps there are still a few of us virgin enthusiasts out there. Love them or hate them, I have a few theories about the big deal with all the virgins.

An innocent heroine paired with an experienced hero ups the level of sexiness. True statement, in my opinion. Mind you, the power dynamic here is very fragile and must be handled with care. Both lovers have power in this scenario.

Also, a virgin’s first time offers so very much interesting fodder to fill out a love scene. Every romance author approaches love scenes differently, but for me, I don’t really graphically describe sex if it does not advance the story and/or up the stakes. In other words, the interlude must be remarkable and worth spelling out for me to write it. Beginners certainly give me something to write about.

Also, virgins are historically accurate.

Also, we were all (or still may be) virgins, so we can relate.

Also—well, maybe this is more like “primarily” for me—if you know me in real life, you know that I’m an old-fashioned person by nature, and virgins are simply my preferred jam.

That said, virginal heroines should not be defined by their sexual experience (or lack there of) outside the bedroom. A Charis Michaels virgin will never be childlike or naïve, she will not require protection or hand-holding or instruction, she is not meek or marginalized or taken for granted or under the thumb of a man. Inside the bedroom (or carriage or stable, etc.), this heroine has sex with only one man—the hero—and he values it.

While I’m at it, I’ll just toss in a second part of my preferred fantasy, and that is the hero and virginal heroine are married when they make love. They might be strangers, they might not even be fully in love (yet), but they are married. This feels safe and secure to me.

As I said: outdated and not-progressive, but I like what I like and I write what I write.

But First, A Disclaimer

The very first inkling of an idea for V&V was the notion that, on his wedding night, a hero discovers a scar on the heroine’s shoulder that suggests she has misrepresented herself. That is, a hero finds out too late that his new wife is not a virgin; that she appears one thing but turns out to be another in a way that feels duplicitous and like a betrayal.

Despite this, I wanted him to be so very attracted to her, he could resist making love to her.

When they have their wedding night, he discovers that she is a virgin after all. Recovering from this (for them both) is the conflict of the book.

It’s an old-school, old-fashioned romance scenario that is actually so grandmotherly, I feel like it needs a disclaimer. So here we go—disclaimed: I am aware that a hero’s preoccupation with a heroine’s virginity is stale and backward-looking and unpopular. I hope I have made it…if not progressive, at least supported by a “why.”

But back to the scenario. So, how do you create heroine who seems like a virgin…but then seems not to be a virgin…but then really is? I mean, without gynecological exams?

I opened the book with the flashback of the hero and heroine trapped against their will in the brothel. And then I made one of them mute. This gave the hero and heroine a shared history, albeit a history with a lot of holes and questions. The next thing we know, they are crawling out a window (which was my second inkling of an idea for this book).

And Also: Fiction from Life

Just a few of the elements from The Virgin and the Viscount that came from IRL….

In the British Museum scene, Rainsleigh tells the story of trying to enroll in boarding school without his parents. He rides to Eaton alone with meager supplies and tries to sign up. Tragically, he is turned away because his crude education has left him barely able to read or write. This flashback is loosely based on my own family story of a relative in the 1920s who left his uncle’s farm to enroll in college, only to be informed by faculty that he would need to attend high school first. Like Rainsleigh, he returned home, studied on his own, and returned in a few years to succeed.

And, the viscount’s family estate, Rossmore Court, is named after the apartment building in which my husband and I lived as newlyweds in London.

Book Extras

The Virgin and the Viscount

Enjoy an Excerpt

The Virgin and the Viscount

Buy your copy →

Read or write reviews on Goodreads →

. . . . . .

Prologue

On April 12, 1809, Franklin “Frankie” Courtland, sixth Viscount Rainsleigh, tripped on a root in the bottom of a riverbed and drowned. He was drunk at the time, picnicking with friends on the banks of the River Wylye. According to an account later given to the magistrate, his lordship simply fell over, bumped into a fallen log, and sank.

It was there he remained—“enjoying the cool,” or so his friends believed—until he became too heavy, too slippery, and, alas, too dead to revive. But they did dislodge him, and after that, they claimed he floated to the surface, bobbed several times, and then gently glided downstream. He was later found just before sunset, face down and bloated (in life, as also in death), beached on a pebble shoal near Codford.

At the time the elder Courtland was sinking to the bottom of the river, his son and heir, Bryson, was hunched over a desk in the offices of his fledgling shipping company, waiting for the very moment his father would die. It had been an exceedingly long, progressively humiliating wait. Years long—nay, decades.

Luckily for Bryson, for his ships and his future, he was capable of doing more things at once than waiting, and while his father drank and debauched his way through all respectability and life, Bryson worked.

It was unthinkable for a young heir and nobleman to “work,” but Bryson was given little choice, considering the impoverished state of the Rainsleigh viscountcy. He was scarcely eleven years of age when he made his first foray into labor, and not so many years after, into private enterprise. His life in work had not ceased since. On the rare occasion that he didn’t work, he studied.

With his meager earnings (he began by punting boats on the very river in which his father later drowned), he made meager investments. These investments reaped small gains—first in shares in the punting station; later in property along the water; later still in other industry up and down the river.

Bryson lived modestly, worked ceaselessly, and spared only enough to pay his way through Cambridge, bring up his brother, and see him educated him as well. Every guinea earned was reinvested. He repeated the process again and again, a little less meagerly each time ’round.

By the time the viscount’s self-destructive lifestyle wrought his river- and drink-soaked end, Bryson had managed to accrue a small fortune, launch a company that built and sailed ships, and construct an elaborate plan for what he would do when his father finally cocked up his toes and died.

When at last that day came, Bryson had but one complaint: it took fifty-two hours for the constable to find him. He was a viscount for two days before anyone, including himself, even knew it.

But two days was a trifle compared to a lifetime of waiting. And on the day he learned of his inheritance—nay, the very hour—he launched his long-awaited plan.

By three o’clock on the fourth day, he’d razed the rotting, reeking east wing of the family estate in Wiltshire to the ground.

Within the week, he’d extracted his mother from the west wing and shipped her and a contingent of discreet caregivers to a villa in Spain.

Within the month, he’d sold every stick of furniture, every remaining fork and dish, every sweat-soaked toga and opium-tinged gown. He burned the drapes, burned the rugs, burned the tapestries. He delivered the half-starved horses and the fighting dogs to an agricultural college and pensioned off the remaining staff.

By the six-week mark, he’d unloaded the London townhome—sold at auction to the highest bidder—and with it, the broken-down carriage, his father’s dusty arsenal, what was left of the wine stores, and all the lurid art.

It was a whirlwind evacuation—a gutting, really—and no one among polite society had ever witnessed a son or heir take such absolute control and haul away so much family or property quite so fast.

But no one among polite society was acquainted with Bryson Anders Courtland, the new Viscount Rainsleigh.

And no one understood that it was not so much an ending as it was an entirely fresh start. Once the tearing down ceased, the rebuilding could begin. New viscountcy, new money, new respect, new life.

It was an enterprise into which Bryson threw himself like no other. Unlike all others, however, he could do only so much, one man, alone. For this, he would require another. A partner. Someone with whom he could work together toward a common goal. A collaborator who emulated his precise, immaculate manner. A matriarch, discreet and pure. A paragon of correctness. A viscountess. A proper, perfect wife.

Chapter One

No. 22 Henrietta Place

Mayfair, London

May 1811

“Will that be all, my lord?” Cecil Dunhip peered over the edge of his thick portfolio and raised his brows.

Bryson Courtland, Viscount Rainsleigh, pushed back against the soft leather of his chair and breathed a heavy, agitated sigh. “Teatime, already, Dunhip? It’s only half past one.”

The secretary’s swollen cheeks shot crimson, and he shook his head, his three chins keeping frantic time. “Begging your pardon, my lord. Of course, by that I did not mean to imply that I required—”

“Easy, Dunhip.” Rainsleigh tossed his pen to the blotter. “You’ll have your tea. But I do have one thing more.” He took up his agenda and glared at the hastily scrawled last line.

Wife, read the note.

Solve

Marry by year’s end.

The viscount looked away. “I’ll need to go about the business of getting a wife.”

Dunhip blinked and inclined his head. He raised his pen high above the parchment, ever ready. “The business of getting a . . .”

Rainsleigh folded the agenda into the shape of a bird and sailed it into the fire. “This townhouse is complete. I’m in London now year-round. It was always the next thing.” He paused. “I’m not a randy bachelor, and I won’t be seen as such. The natural next step is to find a mate, carry on as husband and wife, fill the nursery, et cetera, et cetera. Besides this charity prize, I have no reason to put it off. I need to acquire a proper viscountess and start a family.”

Dunhip stared across the desk, his mouth slightly ajar. Rainsleigh raised one eyebrow. He hadn’t wasted time or energy on female distraction these last diligent years, but he was hardly a monk. Surely the man would not make him say it again.

“Very good, my lord,” agreed Dunhip, idling only a fraction more. His face was impassive as he began to scribble. What notes the man took down, the viscount couldn’t guess. Rainsleigh’s own strategy for wife procurement was vague and theoretical at best, and Dunhip was a confirmed bachelor who lived with his mother. What could he possibly add?

Still, they had to begin somewhere. To his credit, Dunhip shed all hint of challenge and began to pepper the viscount with questions.

Would his lordship prefer a lady from here in London, or should the whole of Britain be considered? What ages appealed to his lordship? With regard to the look of the girl, should the candidates appear olive-skinned and raven-haired, or pale and fair? Should their figures be reedy or robust? And what of the demeanor of the candidates? Bookish or social? Serious or gay?

Straightforward, sensible questions, these. Rainsleigh knew Dunhip would approach the whole thing methodically. He was just about to venture thoughtful answers when his library door swung open and crashed against the wall.

“I always announce myself,” called a voice from beyond the door. “There’s a good man. Trust me, his lordship prefers it.”

Dunhip slapped his portfolio shut and spun toward the sound. Rainsleigh closed his eyes. Finally, he thought, drawing a grateful breath. Thank God.

“Ah, there you are!” said the voice, now attached to a man. Tall, lanky, untucked. Clothes wrinkled, boots caked in mud. A three-day growth of beard.

“Beau.” Rainsleigh leaned back in his chair, crossing his arms over his chest.

His brother whipped off his hat and spun it into a chair. “Before God. Before man. Before—oh, what the hell, Dunhip, we’ll include you with the men.”

Beau Courtland strode into the room, looking around the spacious library with a low whistle. “Wasn’t sure I had the correct street; then I saw the castle. Three-times larger than every other house in the vicinity—and I knew.”

“My lord! Apologies!” Rainsleigh’s butler, Sewell, scrambled through the door behind his brother. “This fellow would not permit me to announce him. I did not realize you were—”

“Expecting him? How could I”—Rainsleigh sighed—“when I believed him to be in India? Don’t bother, Sewell. This fellow is my brother, Beauregard Court—”

“Damn it, Bryson, for God’s sake, mind the name,” Beau interrupted. “Do me this one, small favor.” He turned to the gawking butler and held out his hand. “Beau Courtland. How do you do?” Sewell stared in uncomfortable confusion.

Bryson watched him. “Do you have baggage?”

“I’m not taking a room, if that’s what you mean.”

“You look like a sailor and smell like a still. I hope you’ll stay long enough for a wash and shave and procure a clean set of clothes.” He nodded to the secretary. “That will be all for this morning, Dunhip.”

“Dunhip, old man,” said Beau, slapping both hands on the man’s shoulders, shoving him back into his chair, “still taking down every golden utterance my brother says? Who knew your chubby fingers could write so fast? Kindly remind my brother that I look like a sailor because I am a sailor.”

Bryson narrowed his eyes. “You have no title whatsoever—none of which I am aware.” His brother did not bother to correct him, and Rainsleigh tried again. “What are you doing here?”

“India became too warm for my taste.” Beau circled an empty chair and then sprawled into it.

“Too occupied to send word?”

“I could ask the same thing of you.”

Rainsleigh sighed. “What word? I’m not a shiftless resident of the world at large. I am here, as I always am, as you clearly knew, considering you’re slouched in my library.”

“No, you’re not always in London,” countered his brother. “You’re usually in Wiltshire…in that ancient pile of freezing rock, counting sheep and money with Dunhip, here. I disembarked three days ago, if you must know, but I only learned you were in town today. Read it in the bloody papers.”

Bryson eyed him, weighing his options. He couldn’t have asked for a more opportune inroad to a conversation that was long overdue. But experience had taught him to tread lightly. His brother had been known to bolt if he said too much—if he expected too much.

“I’ve moved to London to be closer to the shipyard,” Bryson told him. “We’ll launch a new ship next year. But perhaps that’s what you read. It’s a venture in which I hope you will take no small amount of interest.”

“Hmmm,” said his brother, who managed to look bored and restless at the same time. He closed his eyes.

“And”—Rainsleigh paused—“I’m in London to find a wife.”

Beau opened one eye. “I beg your pardon?”

“Yes, you heard. I intend to pay you to use whatever you may have gleaned in the Royal Navy to captain my new ship.”

“Not the bloody boat,” said Beau, sitting up in his chair. “The bit about a wife. Surely you’re joking? How the devil will a wife fit into your ambition to make more money, build more boats, and prove to the world that you’re not Father?”

Bryson sighed. “I see your impression of my life equals the pointlessness and lack of regard with which I view yours.”

“One thing I don’t do is judge. If you want to make money and prove to the world that you’re a bloody saint, that is your prerogative. It’s my prerogative to heckle you from the aisle. But a wife? Truly? When have you ever spared time for a female?”

“Clever. As always. I suppose you won’t mind if I marry and turn out a handful of heirs? You’d likely never inherit if I have a son.”

“The chief reason,” Beau said with a sigh, reclining again, “that I will be the first to congratulate the lucky miss, whoever she may be. Godspeed, Bryse. Honestly. Marry immediately and conceive a copious number of sons. The farther I am from the title, the better. God knows you’ll be popular on the marriage mart. All your lovely money. The shiny new polish you’ve put on the title.” He made a low whistling noise.

“Yes, well, that remains to be seen,” Bryson said. “However, I won’t be subjecting myself to the so-called ‘marriage mart.’ Dunhip?” He turned to his his secretary“You might as well take this down, as you’re still here.”

“No marriage mart?” Beau said, marveling. “This is a shock. I thought you were incapable of straying from convention. You know this is how the authentic aristocrats do it.”

Bryson pushed back from his desk. “I loathe that statement, and you know it. Our title is one of the oldest in England. We are authentic. Which is why I’ll go about finding a wife any way I please.”

“Oh my God,” Beau said, “you’re afraid they won’t let you in. After all this time and all your money, you think they’ll withhold their precious, blue-blooded daughters from your tainted fingers. You’re not Father, Bryson. If you want a debutante, you should have one.”

“It’s not the rejection, although I’ve never seen you endeavor to be received anywhere but the corner public house.” He stood. “The shipping venture is my first priority, and I haven’t the time to flit about from drawing room to theatre box, passing brief moments with adolescents about whom I ultimately know very little. Proficiency at idle chatter is no proof of character. When you consider the whole business practically, as I have—as I will—you’ll see it is not a debutante that I want.” He walked to the alcove window that overlooked the garden.

Beau drawled, “No debutante, then. Do as you like. Why I would expect anything less? You’ll forgive me if I cannot get the scene out of my head: You, standing in the corner of a ballroom at five o’clock in the afternoon, sipping tepid punch and discussing needlework, while a crowd of eager seventeen-year-olds and the mercenaries they call chaperones bat their eyelashes at you. You cannot possibly think of spoiling that for me.”

“Yes, but I’m not looking for a seventeen-year-old, eyelash-batting wife. A respected family will be important, of course. It is imperative for my future children that my wife be quality.”

“Dunhip, I’d underline that twice, mate,” Beau said. “Quality.”

Bryson ignored him. “But the other hallmarks of, er, gently bred maidenhood hold no interest for me. I don’t care about form or figure, or even beauty, for that matter. I don’t care about wit or clever banter. Obviously, I’ve no need for a dowry. All I want is someone who is morally upright to a fault. Who is pure. Who can be a proper hostess, bear me healthy sons, and remain faithful to me and to our family.” He looked back at his brother.

“You’re looking for the opposite of Mother.”

“Yes,” he said grimly, uncomfortable with Beau’s bald-faced honesty. “I am looking for the opposite of Mother.”

Beau nodded. He rolled from his chair. Through the window, a finch lit on the stone fountain in the garden, and they watched it in silence.

When Bryson went on, his voice was low. “I know you would prefer that I speak less frankly. To be always in jest, like you. But it can never be said enough: no aspect of our years at Rossmore Court need ever be repeated, Beau. Not a single miserable moment, save that we rely upon each other.”

Beau turned to him. “I hope by that you don’t mean that I, too, will be expected to marry a plain, penniless, pious wife who holds no attraction for me.”

Bryson laughed. His brother was shiftless and randy, and he drank far too much, but he was amusing. He slapped him on the back and caught his shoulder, hanging on. “No, brother,” he said. “Leave that to me. Leave that to me.”

. . . . . .

Wiltshire, England

Fifteen years prior…

“Leave it to you, should I?”

Frankie Courtland, Viscount Rainsleigh, held his son painfully by the left arm and dragged him down the hall. On Bryson’s right, his cousin Kenneth pinched his shoulder with a thumb and forefinger and kneed him in the kidney. Bryson was nineteen, tall, and strong from punting boats on the river. As victims went, he wasn’t an easy boy to drag from a house or stuff into a carriage. So they came for him in the dead of night and set upon him when he was fast asleep.

“Let me go,” he ground out, scrambling to find his feet. “I will not go.”

Laughter, wheezing, profanity. They hauled him down the main stairwell of Rossmore Court and through the great hall. The front door stood open, and they chucked him onto the stoop.

His father stalked him. “You will go.” His voice had gone breezy and light, but Bryson knew what to expect, and he braced himself. The backhand was swift, opening his lip and speckling his vision with tiny flecks of white light. Bryson reeled, and they pounced again.

“As will your cousin Kenneth, your uncle, and myself,” Lord Rainsleigh went on. “Tonight, my pious boy, you’ll become a man.”

The starless night was disorienting, and they easily overtook him, fighting, one against three. A carriage stood ready in the drive, and they shoved him in and climbed in behind.

Bryson scrambled to the far bench. “You plan to forcibly carry me inside? Haul me around like last week’s wash? Against my will? While people watch?”

“Be agreeable for once in your life. It’ll be over before you know it, and then you’ll be fighting to get back in the wench’s arms instead of conspiring to stay out.”

“Ah,” Bryson scoffed, “this is for my own good, is it?”

“See for yourself.”

“As if you ever had the smallest interest in anyone’s good but your own, particularly mine. You can go to hell.”

“Oh, I intend to,” said his father. “But first I will go to this brothel, as will your cousin and your uncle. As will you. We’re all going. So you can cease your sanctimonious babble and prissy crying about my miserable turn as your father. It spoils everyone’s fun, not to mention that it makes me drowsy.” He leaned his head back on the seat. “How tiresome your pious sneering has grown… all summer long… carrying on like lord of the manor… as if you’re better than the rest of us.”

“This is because I am better than you,” Bryson said. “But that’s what bothers you, isn’t it? This has nothing to do with how I conduct my life. I’m keeping the lot of you out of debtor’s prison; meanwhile, the world knows you’re a degenerate wastrel of man, an addict, and you don’t deserve to be viscount.”

Lord Rainsleigh chuckled. “Call me names if it cheers you, Bryson. But let us not forget that I am not the nineteen-year-old virgin in the carriage.”

“What could you possibly care about that?” Bryson worked to make his voice sound light.

“Why, it taints the otherwise virile reputation of the Rainsleigh crest, of course.” His father laughed. “You don’t want to make a name for yourself as a sodomite, do you?”

“Eloquently put, as always,” Bryson ground out, speaking over their laughter. “I have school at the end of the week. St. James is the opposite direction.”

“Oh, we’re not going to London!” This from his cousin Kenneth, on an eager laugh. Bryson’s father silenced him with a swift elbow to the rib.

Bryson looked out the window. “If we’re not going to St. James, then where are you taking me?”

“Kenneth cannot contain his excitement”—the viscount glared at the fat relation—“because he has located an establishment in Southwark where we all may indulge in delights that suit our particular needs. Scouted it out himself last night. Do not fret, Bryson; there will be an experienced wench there, well suited to your nervous, novice bumblings.”

Bryson let the curtain drop. “Southwark? The river slum? You’re joking.”

His father raised his eyebrows cryptically, flashing a cruel grin.

Bryson pressed. “If you must go whoring, why not go to Town? To somewhere civilized and comfortable? With clean sheets and a decent meal, for God’s sake?”

“St. James has grown . . . tiresome,” his father said, turning to look out the window.

Of course, Bryson thought, coming to understand. “Your reputation precedes you. They’ve shut you out. That’s it, isn’t it?” He laughed. “Excellent work, my lord. Excellent. You’re a peer of the realm who can’t even fornicate in bloody St. James. Good God, Father, is there no person or establishment that you will not offend?”

“You’re only making it worse for yourself, boy.” His father yawned.

“No, my lord,” Bryson said. “You make it worse with every breath you draw.”

Chapter Two

Denby House

Grosvenor Square

May 1811

The breakfast room of Denby House in Grosvenor Square was canvassed with maps. Greater London. Mayfair. Chelsea. Seven Dials. The River Thames. They covered the dining table, smothered the centerpiece, and draped the chairs. A magnified rendering of Hyde Park lay unfurled on the floor.

In the corner of the table, leaning over the largest sheet, Lady Elisabeth Hamilton-Baythes studied the hive of crooked streets that crisscrossed the south bank just beyond London Bridge.

In and out. Over, then south. Down the alley . . . Using a tiny white spoon from the sugar dish, she traced routes. The fastest escape. The least likely to flood in case of rain. A second route to lose pursuers. Side streets in which to hide. A switchback. There was potential, but also the risk of becoming disoriented in the narrow, winding mews.

“Oh, darling! Must you?”

Elisabeth looked up. Aunt Lillian stood in the doorway, balancing a wobbly green pear on a plate.

“Hello,” Elisabeth said, blowing a wisp of hair from her face. “It’s awful, I know. I had hoped you’d taken breakfast in your rooms so as not to be subjected.” She tossed the spoon into the Thames.

Aunt Lillian affected a patient expression and drifted to the sideboard with the pear.

“The raiding team will do deep reconnaissance tonight,” Elisabeth said. “These couldn’t wait for the office. Ah, yes. Look. Here’s a spot for you . . .”—she pointed to the map at the end of the table—“in, er, on Hampstead.”

Lillian settled near the window. “The mess can be tolerated, but these maps force me to acknowledge the gravely dangerous nature of the work you do. I prefer to imagine you seated at a sunny desk, you know. Writing letters or tallying up contributions. On occasion, perhaps you impart the stray encouragement to a young girl. Instruct her on serving tea. Or arranging flowers in a vase. But this? Elisabeth? You promised.”

“Hmmm.” Elisabeth nodded, turning back to the maps. “Yes, but we only arrange flowers on Tuesdays, Aunt, and today is Friday.”

The countess sighed and took up the pear.

“But you needn’t worry,” said Elisabeth. “I’ve kept my promise. I only assist with the planning. I’m never in the street. Stoker would soon edge me out, you know, if I did not acquire this working knowledge on my own. I don’t know the river as he does, but I can learn.” She straightened and looked around. “Quite a lot of mess for your breakfast, I’m afraid. The most convenient place would have been the kitchens, but Cook wouldn’t allow it. She was already in the throes of culinary hysteria. Said you’re hosting a dinner?”

Lillian drew her eyebrows. “Yes, but you knew this. In honor of the new viscount, just moved to town. He’s a parliamentary connection of Lord Beecham. Lady Beecham and I will host together. Feign ignorance all you like, but I want you there, Elisabeth. No excuses, please.” She sliced the fruit and took a dainty bite. “ ’Tis but a meal and conversation. The only guests will be the viscount, Lord and Lady Beecham, and a few old friends. Some ladies not much younger than yourself—”

“Oh, no.” Elisabeth pointed at her aunt with a rolled map. “Young ladies? Young ladies only mean one thing: this viscount is a bachelor. Admit it. And you’re tossing me in on the vain hope that he won’t notice that I’m too old and too preoccupied with my work to be anyone’s wife.” She crossed her arms over her chest. “We’ve been over this, Aunt Lillian. It’s a poor strategy. And it makes everyone uncomfortable. Especially me.”

“Stop. You are young and beautiful and will outshine every girl there, despite your age. Be preoccupied if you like . . . although I’d term it more like ‘enthusiasm.’ Discuss your foundation with the guests, but wear a new dress when you do it. Allow Bea to style your hair. It won’t matter what shocking thing you say if you look your very best when you say it.”

Elisabeth shook her head and reached for another map. “Has it occurred to you, Aunt, that if I dressed as fashionably as you liked, I might supersede the beauty preeminence that so rightfully belongs to you in this house?”

“But this is what we want, of course. You are young and beautiful. You aren’t forced to eat raw fruit—better intended for the horses than the people—in order to remain slender and attractive.” She took another bite. “When I was a girl, I traveled to Paris to be outfitted in styles that were seasons away from the drawing rooms of London. Before I was parceled off to marry decrepit Lord Banning, Mama’s front door saw a continuous stream of gentleman callers.”

“Which was one of the reasons you were parceled off, or so I hear,” Elisabeth said absently, returning to her map. “I suppose this is what you want for me. A line of men wrapping around the house? So many men that you’re forced to marry me off simply to be rid of the bother?”

“Ah, but you must know that I want what you want, darling. My point is merely that you are only young once—”

“Ah, but perhaps I’ll be beautiful forever, like you, Aunt.”

“That is entirely beside the point. Do not distract me with compliments. No doubt you will be beautiful forever. But regardless, you will never be as beautiful as when you are young.” She took up the fruit again but then put it down. “And why shouldn’t you let me dress you? Why won’t you indulge your old aunt in being more of a true mother to you?”

“Oh, Aunt Lillian . . .” Elisabeth sighed. She crossed to the back of her aunt’s chair and draped her arms around her shoulders. “You have been an ideal mother to me, as you well know. You restored my life when I wanted to roll up into a little ball and float away. You made me a happy girl where a miserable girl could have been. This is far more valuable to me than fine clothes or hats or shoes or bags. You are the great unsettling beauty, Aunt, and you know it. The infamous Countess of Banning. I am the niece who has other plans.”

Elisabeth dipped to give her aunt a kiss on the cheek, and the door from the kitchens swung open. Quincy strode into the breakfast room bearing a silver tray of fragrant scones. “These,” boomed the gardener, “have just come from the oven, my lady. Made with our very own gooseberries from the garden.”

Elisabeth chuckled at her aunt’s exasperated sigh. Lillian turned away, but Quincy was not deterred. Elisabeth helped him clear away maps so he could edge out Lillian’s pear with the heaping tray. The countess squinted at it with open animosity.

“Pruning today, Quincy?” asked Elisabeth.

“Aye. Only the west garden remains.”

Of all the ornately decorated rooms in Denby House, Benjamin Quincy was most out of place in the frilly, pale-pink breakfast room. His well-worn leathers and salt-and-pepper beard were like an unfinished oak beam against the countess’s chintz. When the house was empty of outsiders, Quincy moved freely through every room, pink or otherwise, with a verbose, earthy jocularity that was distinctly, endearingly Suffolk woodsman. Despite Lillian’s exaggerated irritation, Elisabeth knew her aunt would have him no other way. The countess had been in love with her gardener since the summer her husband, the old earl, had died and left her a young widow, some twenty years ago.

“When I’ve finished,” Quincy went on, “every bed will be cut back for the summer. How do you like that?” He winked, collected three scones, and strode out the door with a loud whistle.

“He would fatten me up to the size of an ox,” vowed Lillian, making a show of pushing the tray away.

“Oh, surely one cannot hurt.” Elisabeth took up a scone and nibbled.

“I shall eat the whole tray if you will come to dinner tonight. Did I mention that it was for charity? Knowing this, I should think you would want to attend.”

“Hmmm,” Elisabeth mused. She began rolling the maps and sliding them into a basket. “You said it was for Lord Beecham’s parliamentary something-or-other.”

“Yes, yes, the viscount. Beecham arranged the meal because they are acquainted. But Lady Beecham and I intend to approach him about our committee for the hospital expansion. You’ve coerced me to join a cause, Elisabeth. The least you could do is support my effort to raise funds. They say he’s very rich . . .”

“Is that what they say?” She rolled another map.

“And now he’s just announced his plan to donate a sizable sum to three worthy charities in town. ’Tis a competition, in a way. The three winning charities will each receive a donation. And why shouldn’t one of them go to the hospital? We are determined to reach him before those vultures from the Widows and Orphans League.”

“Never let it be said that the widows and orphans have an advantage. But this is a bit provoking, isn’t it? Forcing charities to compete? Why doesn’t this person simply select one charity and quietly donate the whole sum?”

“Publicity, I suppose. He’s been working for an age to rehabilitate the reputation of his title and family name. Wants to be viewed as the right sort. Generous. Noble.” She took another nibble of pear. “But perhaps you should toss your hat into the ring, Elisabeth. For your foundation? Win the charity prize for your girls. There now, you see? Another reason to attend.”

“If his goal is to generate publicity, the last cause this viscount will wish to support is mine. We never get the flashy donations. More of the same, really.” Elisabeth ran a charity that rescued girls from the streets of London and set them up in a better life. She looked at her aunt. “But you’ve invited the man to dinner in order to win his favor? Is this how the decision is to be made? He’ll give the prize to whoever makes the biggest fuss?”

“Oh, no. There’ll be an application process, and interview, a tour of the facilities. We’ll do all of this, naturally. But Lady Beecham felt we might sweeten the pot with a lovely dinner. Considering he’s new to town. It’s why we’ve invited the young ladies—yourself included.” She shot her niece a pointed look. “Rumor is, he’s come to London looking for a wife. We simply want to appear helpful and accommodating. It’s the least we could do.”

“The very least.” Elisabeth rolled another map. “Quite an effort for a charity gift. How much is the prize?”

Lillian dabbed her lips with a napkin. “Oh, ’tis a thousand pounds, each prize.”

Elisabeth’s head shot up. “You jest! A thousand pounds? No one gives away that amount of money unless he’s dead. Why, a charity could realize the goals of its wildest dreams with a donation of that size.”

Aunt Lillian nodded, “ ’Tis no jest. But I can’t believe you haven’t heard of this, darling. It was a headline in today’s Times. According to the article, the viscount has money to spare. He’s spent two years and God-knows-how-much restoring a mansion near Cavendish Square. In Henrietta Place, just down from old Lady Frinfrock. You remember Lady Frinfrock, from St. George’s? She’ll be here tonight as well, which is very rare. She’s not been seen out for an age. It would appear everyone wants a glimpse of the viscount.”

“Forgive me if I haven’t kept up on who spent what to live where, but a thousand pounds. Truly?”

“Oh, yes. And to three different groups. Three thousand pounds in all.” Lillian paused. “If it’s a splash he wants, he’ll get one with that sum.” She chuckled to herself. “Aren’t you curious about the prize or the philanthropist, Elisabeth? Even a little?”

“The prize? Possibly. The philanthropist? Not really.” She stooped to retrieve the maps from the floor.

“Even so,” said her aunt, “I should like you to make the effort. Wear a pretty dress. Wear a flower in your hair.”

Elisabeth tucked the maps beneath her arm and sailed to the door. “And ever the burden grows,” she said.

“What burden?” her aunt called after her. “ ’Tis but a meal—three hours at most.” Her voice raised to a shout. “You’ll do this one small favor to help me, won’t you, darling?”

“I don’t see how this is helping,” Elisabeth replied, already moving on.

. . . . . .

The Bronze Root Tavern

Southwark Docks on the River Thames

Fifteen years prior…

“I don’t see how this is helping,” Elisabeth whispered to Marie, scuttling down a cramped brothel hallway in the dark. “Please, Marie! This is not helping me.”

“Hush,” hissed Marie, whipping them around a corner and falling back against the wall, “and come on!”

“How is it helping me to run deeper into the building?” Elisabeth peered around the corner at the main stair, which grew farther away with every turn. “We’re going the wrong direction!”

“Lesser of two evils,” Marie whispered. “I’m rescuing you from the old man—the father. There’ll be no getting around the son.”

“But I don’t want either of them!”

Marie laughed. “You only think that because you don’t know what a rotter the father can be. Coming here especially for you, he is. Partial to soft-skinned innocents. Virgins, the sick bastard. For the son, they’ve asked for an experienced professional. Like me. If it really is his first time, he’ll be harmless—even for you. Far better than the father, believe me. The son won’t last ten seconds.” She laughed.

“But Marie.” Elisabeth fought for control. “We talked about an escape. Actual freedom. All the way outside. Not another room with another man!”

“Ha.” Marie chuckled, drawing a shaky hand to her brow. “What we want doesn’t matter now, does it? Means to an end, this is. Stop arguing, and do as I say. You will go to the boy—the son. Best I can do. Why don’t you tell him what’s happened?” she went on. “Tell him your parents have been shot, and you’ve been left here to rot. Let him hear that plummy accent of yours.” She shrugged. “Maybe he’ll be the one to get you all the way out.”

“But you can get me out,” Elisabeth insisted. “We can both go. Together. Out the front door. Or the back door. Out any door.”

Marie only laughed.

“You’re smarter than these men, Marie,” Elisabeth said. “The man in charge? He may be strong, but you are clever, and I am fast.”

Marie shook her head. “Forget about the doors. Forget about me. You’ve got one job tonight, and that’s to please the young lord. Whatever he wants, you do it. Do it with a smile on your pretty face. And when it’s all said and done, ask him for a little boost, patient and pretty, like. I’ll keep the father busy all night long. He’ll never know the difference.”

“There must be another way,” Elisabeth whispered, her voice cracking.

Marie shook her head. “Been here five years, since I was younger than you, and I’ve not seen it.” She studied Elisabeth with sad, shrewd eyes and yanked the remnants of Elisabeth’s ill-fitting shift back over her wounded shoulder. “We’ve had some bit of luck—with those men last night, sniffing around, getting a nice long look at you. Their little taste gave us fair warning, didn’t it? And when do we ever get that?”

Elisabeth nearly retched at the memory of the men who had arrived the previous night. She’d been dragged her from her bed and presented to them like a meal. At the urging of the eager proprietor, they had ogled her, pinched her—touched her. The feel of their hands on her body had made her actually pray for death.

“It cannot be so far to London,” Elisabeth had whispered to the wall. “My parents and I were only to Windsor Road when our carriage was attacked. The highwaymen rode only a few hours to reach this place.” Elisabeth could recite the circumstances of the last forty-eight hours, but she could not dwell on it. She’d set aside the sickening grief of her parents’ murders and her abduction, and her unspeakable first night in this place. She would not think of her future without her mother and father. She would not think of the searing burn on her shoulder. Instead, survival had become her entire world. It was survival or choking on her own fear and pain.

She implored Marie again. “If it’s even a day’s walk to town, I can make it on foot, truly I can.”

“Put it out of your mind,” Marie scolded. “This won’t be so bad. A lot easier than walking back to London in the wet, I’ll tell you that.”

“Marie,” Elisabeth’s voice broke. “I cannot be given to any of them.”

Marie went on as if she hadn’t heard. “The young men are quite shy, really. Timid-like. Easy to manage. How old are you? Sixteen? Seventeen?”

“Fifteen,” Elisabeth said. “Only just.”

“Oh. Well.” She thought this over. “Nothing we can do about that, is it? The old lord wanted a young one, didn’t he? But the boy will expect experience, remember. He will expect me.”

“This is not helping me,” Elisabeth repeated. She would say it again and again and again.

“It will be what you make it. Tell him who you are; tell him what happened to you and your parents. Show him the mark that Snill burned into your shoulder. It’ll heal, by the way. Leave a scar, but it will not pain you forever.”

“I don’t want to talk to him! I don’t want to see him at all. Marie, please. I cannot do this.” Elisabeth pulled the course, torn garment over the fiery wound on her shoulder.

“You can do it, and you will do it,” Marie said, taking her by the hand.

Voices, loud and slurred, intruded on the hushed tones of their conversation, and Marie held up a hand to quiet her. It was a group. Four men, maybe five. In the taproom below. One of them angry, others laughing. A piece of furniture splintered. Elisabeth squeezed her eyes shut.

“They’ve come,” whispered Marie. “ ’Tis time. We’ll stash you in my room, and I will go to where Snill left you to wait for the father. Exactly as I’ve said, little miss,” she continued, pulling Elisabeth along. “You must do everything exactly as I’ve said.”

Chapter Three

Denby House

Grosvenor Square

May 1811

It rained the night of the Countess’s dinner, a foggy, fitting damp. Rainsleigh welcomed it—what else could he expect for his first foray into the inner sanctum of London’s social elite? He’d toiled years for an invitation such as this, but he refused to sail into the evening thinking it would be easy. Old habits died hard. A lifetime of exclusion had prepared him. At the very least, it should rain.

Ah, but it was just a meal, and on a day when Parliament sat. This guaranteed that the dinner would not run long. Few people of distinction would attend. The best wine, he knew, would not be served. Considering the stack of work waiting for him at home and the rare appearance of his brother, Rainsleigh didn’t really even want to attend. What he’d really wanted had been the invitation. Simply to make the bloody list. The real triumph was access. Now that he had it, it meant inane chitchat with lofty strangers. He immediately wished attendance had been optional. Or not tonight.

But he had said that he would come. And he was mildly curious. And really, these sorts of engagements were necessary, he knew, if his ultimate goal was to be regarded as equal. A reclusive viscount would be known as a degenerate one, if no one ever saw him.

Rain meant carriage traffic, lurching and slow, and after ten minutes of waiting, Rainsleigh bade the coachman park behind the last vehicle so he could walk. Soames had outfitted him with hat and umbrella, overcoat and boots. He had not come so far that he could not get wet.

“My lord…” enthused the hostess, Lady Banning, five minutes later, smiling inside the warm confines of her sprawling entry hall. She reached out, two delicate gloved hands clasping his, and ushered him in. “What a pleasure it is to meet you at last. We’re so pleased that you’ve been able to join us on such short notice, especially when you must be terribly preoccupied with settling in.”

Rainsleigh bowed over her hands. “The pleasure is all mine, Lady Banning. It was a delight to receive your invitation. We’re practically neighbors now. You are between my new house and the park.”

“That park!” the countess complained, smiling still. “My niece spends half her time there, regardless of the weather. But you’ve met my niece, Lord Rainsleigh? Lady Elisabeth?”

Rainsleigh bristled. It was common knowledge that he’d been introduced to practically no one, especially young women. He put on a neutral face. “I don’t believe I’ve had the pleasure.”

“I don’t see her at the moment,” Lady Banning said, “but we’ll find her, and you must be introduced. She knows every corner of Hyde Park, especially the damp, boggy bits, judging from the condition of her boots. I’m sure she will be happy to educate you about where the trail has washed out or where the best shade can be found.”

“That would be most useful.”

He bowed again, making way for the dripping older couple behind him. The countess easily soothed them, all sympathy and smiles. Charming woman, he conceded. She’d shown him no veiled slight or indignity. Attractive, too, despite being twenty years his senior.

A footman led him down the wide hall to an adjacent salon. It was a small gathering. Mostly elderly couples and young women. There was a glaring lack of gentlemen and no one easily identifiable as his equal in rank or wealth. Possibly a statement about his inclusion, possibly harmless.

Two more young women strolled into view, which made five girls, all told. He rubbed his jaw. A footman passed with a tray of drinks, and he took a glass, counting in his head. Five young women, the widowed countess, and a clutch of elderly people, old enough to have met Christ. He took a drink. This dinner made no sense.

But now here was Lord Beecham, making for him at a slow waddle from a chair beside the fire.

“Rainsleigh!” the baron called, his politician’s smile wide on his ruddy face. “So good of you to come. Lady Banning and my wife have been determined to welcome you to town before the others.”

“Others?” Rainsleigh took another drink.

“But of course! Point of pride, really. Wanted to be first and to make an impression. You’ve seen the lovely debutantes? Convened the lot—oh, there must be four or five of them—in hopes of lighting the tinder of a brilliant match.”

Rainsleigh choked on his drink. “The young women are for me?”

“Oh, but do not think to keep secrets in this town, old boy. London hostesses can smell a marriage-minded gentleman as far as Middlesex. They’ll know it’s time to get shackled before you do.”

“How accommodating. I hadn’t—”

“But before you become distracted by the young ladies, I must bend your ear about my shipping levy . . .”

And he was off, lobbying on behalf of the maritime legislation he’d been touting to the shipping magnates for weeks. Rainsleigh nodded, only half listening, and allowed his eyes to wander. He surveyed the room.

Four or five young ladies for me? This had not occurred to him. He took another sip. But he had no idea what to do with four or five young ladies. Mincing through marriage prospects was to be Dunhip’s job. Rainsleigh intended to sweep in at the eleventh hour and consider the finalists, perhaps the top four. Or even two.

He narrowed his eyes, studying the girls. My God, but they were young. Barely out of the schoolroom. He was thirty-four years of age, head of his family, shipbuilder, landholder, viscount. Certainly maturity in his future bride was a priority. With maturity would come reserve, calm, discretion, self-control . . .

One of the girls looked up and caught him in a stare. She was tall. Frocked in yellow. Brown hair, strong nose. Rainsleigh considered her. She appeared elegant enough. He gave a curt nod. The girl smiled coquettishly and lowered her eyes without breaking the stare. She blinked. While he watched, she discreetly extended the tip of her tiny pink tongue and licked her upper lip. At him. For him.

Rainsleigh turned away.

No. Absolutely not. No boldness. First and foremost. Especially no provocative, flirtatious boldness. He’d spent his boyhood with a mother who batted eyelashes and licked lips before she even arose from bed. More often than not, a footman walked away in a better mood. It was a disgrace, one of many. He would not repeat the phenomenon with his own wife.

He drained the last of his glass and nodded along to Lord Beecham’s drone, raising his eyebrows in faux interest. He was just about to gesture for another drink when movement caught his attention. A flutter. A flash of blue. Out of sheer boredom, he turned to follow it, craning his head.

It was yet another young woman. In the opposite direction, separate from the party. She was alone, clipping down a staircase at the end of the great hall and holding a piece of unfolded parchment. As she descended, she read. Must be a relative or member of staff, he thought. Clearly, she wasn’t part of the countess’s party. She paid no mind to the raised voices or clinking crystal at the end of the hall, and she was dressed in a simple blue muslin day dress. Rainsleigh almost turned away. Almost, but not quite.

Casually, he looked again.

Perhaps it was that she did not descend the stairs so much as float over them. Purposefully but not stridently. Gracefully but with no flounce. She ignored the handrail and did not glance at the rapidly descending marble beneath her feet. The parchment in her hand obscured her face, but he could make out a serene profile, a small ear.

He looked harder. She appeared . . . Rainsleigh found himself unable to put words precisely how she appeared.

“Rainsleigh? Rainsleigh?”

Lord Beecham called to him from five feet away.

The viscount looked up. The baron stood on the threshold of the salon, sputtering and confused.

“Forgive me,” Rainsleigh said, stepping back to him. “Lord Beecham, do you know that girl, there? On the stairs?” The question was out before he realized. He pointed. “The young lady?”

“Eh?” Beecham craned around.

“No, not in the salon. There, in the hall. She’s just come down the stairs. It’s difficult to see for the parchment in her hand, but I believe she has—” He blinked. “Yes. Her hair is an odd sort of pale ginger.”

Beecham squinted down the hall. The young woman had stopped at a sideboard and was rustling in a drawer. She closed it, took up the paper again, and moved on, still not looking up. Now she walked in their direction but stopped at a closed door, halfway down. She reached for the doorknob and pulled it open, speaking to someone on the other side. She gestured. She nodded. She waved the paper in the air. She moved inside the door a step but not all the way.

Rainsleigh could not see her face. He swore and stepped to the side, angling for a better view.

“Oh, there,” said Beecham, drawing his brows together. “ ’Tis only Lady Elisabeth, the countess’s niece. My wife did not expect her to attend the party, and it appears she was right. Look how she’s dressed at this hour. But she does live here in Denby House. Been a ward of the countess for these many years.”

“Lady Elisabeth,” mumbled Rainsleigh, studying the tall, thin half profile visible behind the standing door. He looked at the baron. “Why is she not expected to attend?”

“Bit of an odd duck, I’m afraid. She’s lived with the countess since her parents were killed in a carriage raid, years ago. Tragic business, really, but she seems well enough. Although she is never really seen out socially, or so they say. Lady Banning never compelled her to make a proper debut, and she did not, as far as I know. Egad, Rainsleigh, with all the other girls here, you’d do well to stay away from that one. On the shelf, really.”

Rainsleigh studied the parts of her he could see beyond the standing open door. The slender point of her shoulders. Her elegant back. The gentle slope of her bottom beneath the soft blue skirt.

A footman walked past her, ferrying drinks on a tray. He offered her a glass, and she used the paper to gently wave him off. The servant proceeded toward Rainsleigh, but she must have called him back because he returned to her. She pivoted, telling him something.

And that’s when he saw her face.

For the second time that night, he could not look away.

Her eyes were light. Blue? Perhaps green. He was too far away to tell.

Her hair, he saw, was not strictly ginger but gold and blonde and pale red, all spun together.

Rainsleigh took an inadvertent step toward her. The footman with the drinks passed him now, and he took a glass, not taking his eyes away.

Without warning, she looked up, and their gazes locked. Her eyes grew huge. She sucked in a startled breath.

For a long, taut moment, they stared.

Beecham, reliably, broke the trance. “Egad, Rainsleigh, but you look as if you’ve seen a ghost. Are you acquainted with Lady Elisabeth?”

Rainsleigh shook his head: one slow, firm shake. He was not.

His mouth had gone strangely dry. His voice was a low rasp. “I’ve never met her before in my life.”

. . . . . .

Fifteen years prior…

Bryson awakened in the world’s smallest, most uncomfortable bed. He blinked at the ceiling, smoky and water-stained, and lifted his head to look at his feet.

Boots, he thought. Thank God. At least they’d left him in his clothes and boots.

His head throbbed. They’d drugged him—his father and his uncle and his cousin Kenneth. Or they’d knocked him out with a blow to the head. Or both. His vision blurred, sharpened, and then blurred again. When it came to the pranks of his father and cousin Kenneth, his priority had always been consciousness. Remain conscious. At all costs. Clearly, he’d failed again.

He swore and shoved up in the damp, unfamiliar bed, willing his eyes to focus. When the room stopped listing, he saw it was small and cold and spare. The adjacent door was closed tight, naturally. If previous abductions were any indication, it would also be locked.

He looked to the opposite wall, and—

Bloody hell. The room was small, cold, spare, and occupied.

Bryson rolled out of bed, blinking against his throbbing headache, and gaped at the silent figure huddled against the far wall.

A girl.

She stood beside a window, clutching a fireplace poker diagonally across her chest. Her hair hung unbound down her back. Her dress, or rather her shift, was marked with an ominous stain that seeped through the fabric at one shoulder. Blood.

He looked at her face. Her eyes were wide with terror.

“Hello,” he said carefully. He held out his hand in a reassuring gesture. “You’re all right.”

He took a step, and she gasped. She pressed herself more tightly against the wall.

“Door,” he told her, taking two steps. “I’m merely going to the door. Is it locked, do you know?”

She didn’t move, but he was careful not to turn his back on her and the poker. He reached for the knob.

“Locked,” he said, gripping the knob more tightly, rattling it left and right. It refused to give, and he added his other hand, his shoulder, his foot, kicking the base with his boot. He forgot about the girl and raged at the unmoving door, shouting profanity and threats.

No one came.

He spun back to the room. “The window,” he said, pointing beside the girl.

“It’s locked,” she said, her first words. He stopped. My God, but she was young. This had been obvious from across the room, but her voice sounded like that of a frightened child. Was she fifteen? Sixteen? He couldn’t guess.

“Careful,” he said, starting again for the window. The girl leapt back and skittered down the wall, wedging herself between a heavy wardrobe and the corner.

He held out a hand to calm her. “Be assured, miss, the sooner I can discover a route to the street, the sooner I will be out of your way.” He peered out the window and swore. They were at least three stories up.

“But you don’t mean to . . .” Her question trailed off.

“I don’t mean to stay the night,” he assured her, feeling around the window facing and clattering the lock. “I don’t mean to stay five minutes, if I can help it.”

She thought about this and then asked, “Can you take me with you?”

His hands stilled. “With me? Take you with me . . . to Cambridge?”

She shook her head. “Take me with you out of this room. Take me out of this building. Out of Southwark. To London?” She raised up a little, having said this. She watched him.

Her eyes, he thought, were a curious color. Aquamarine. So unexpected. He’d prepared himself to be matched with the fattest, most tired, most garish woman in the history of the occupation. Instead, he found himself staring into the aquamarine eyes of a girl who wanted exactly the same thing that he did.

“We’ll go together, then.” The words left his mouth before he’d realized he’d said them. “Why not? Since we’re a team now, could I trouble you for the loan of your poker?” He smiled.

She looked at the iron rod in her hands.

“Window’s painted shut,” he explained. “Many times over. We’ll be here all night if we bother with the lock. If no one came when I raged against the door, I’m doubtful they’ll come at the sound of breaking glass. Especially if you scream.”

“Scream?” she repeated.

“To cover the racket. If you stand by the door and affect something shrill and perhaps a bit desperate, that should do it. You’ll, er, know what’s a common enough sound for a . . . er . . .” He turned back to the window. “For this time of night.”

He saw her think about this. He thought of her shoulder, the fear in her eyes, the torn shift. Likely she’d done enough screaming for a lifetime.

“Or we can give it a go without the scream.” He stretched out his hand and nodded toward the poker. “I’ll let you decide.”

“I can scream,” she said. She knelt and placed the iron poker on the floor and slid it in his direction.

“Right,” he said, scooping it up. “Wait—let’s block the door with this wardrobe, shall we? When they do come, it will slow them down.”

She stood back as he muscled the heavy, uneven piece of furniture in front of the door.

When the wardrobe had been safely lodged against the door, he tapped the sharp end of the pointer three times against the glass, testing it. It would shatter easily with one thrust.

He nodded to her. “Go on, then,” he said.

The girl stood stock-still for three or four beats, and then she took a deep breath, braced herself on the wardrobe, and screamed.

Five minutes later, they hit the wet ground of the alley outside the window with a one, two, smack.

“Bloody hell,” Bryson grumbled, launching from the ground and swatting at his knees. “Not only are my boots scuffed but my trousers torn as well.”

The girl bounced up and scrambled against the wall.

“You all right?” He glanced at the tear in his trousers. “These breeches were new, and I needed them to last for at least a bloody year. Typical. My father does these things intentionally.”

He straightened and looked up and down the alley. “And now where are we? With torn breeches and only two days to get halfway across the country?” He looked at her. “Which way to the river? Do you know?”

She reached for the wall beside her and said nothing.

“The river?” he prompted. “The River Thames? Wide? Dirty? Lots of boats?”

She considered this.

“Separates this sodden slum from the outskirts of London?” he added. “Look, I know you can speak, so please. If you can impart anything about where we are, now is the time to share it. Surely it’s clear that I’m not going to harm you. I only landed on your, er, head when the drainpipe snapped. I lost my hold those last three yards. Sorry.” He grimaced. “You broke my fall. For which I’m grateful.” He flashed her a smile.

She looked away.

“Right.” He sighed. “Let’s try a new tack. What’s happened to your shoulder?”

She shuffled down the wall two more steps. “Stay back,” she whispered.

He nodded. “Right. Very well. I’m back. What’s happened? A cut? Oh, God is it a…” He forgot his promise to stay back and closed in on her. She cowered, flattening against the wall.

“Easy,” he said. “I only want a look.”

“Please,” she whispered brokenly, “do not touch…”

“Bloody hell, it is,” he said, marveling. “You’ve been branded. Is that it? A cattle brand burned into your shoulder?”

She turned her face away and leaned her forehead against the wall.

He peered over her, fighting the urge to pull away the blood-soaked shoulder of her shift. The wound was festering, angry, red and black.

“How far down your back does it stretch?” he whispered. He moved to take better advantage of the moonlight.

Her face crumpled against the wall. She let out a broken sob.

Bryson swore. “Look, we’ve got to get out of here.”

He left her to cross the alley and look around a corner. They would have miles to walk in the cloud-filled darkness before they reached reliable civilization.

“You mentioned London. Is this where you would you like to go? I’ve a schoolmate there who might be persuaded to give me a ride back to Cambridgeshire.”

Her head popped up from the wall. “London—yes, please. I’ll need only the direction to Mayfair. To Grosvenor Square.”

He craned around. “Mayfair? What business do you have in Mayfair?”

She shook her head.

“Right,” he said. He wouldn’t pry. “Mayfair. That is as good a place as any for me to start. We can hardly stay here.” He looked left and right. “The last thing I remember was my father’s carriage rolling over Blackfriars Bridge. If we are near Blackfriars, we can walk to Mayfair by morning. Assuming we can find the direction of the bloody Thames.”

“The river is to the left,” she said. She took a step from the wall.

“Ah, that was going to be my guess. Great minds think alike.”

“It was the smell.”

“Great noses, then.”

“If you please,” she said, louder now, “I cannot be found out. I cannot be taken back. I’ll die before I go back.”

“Then we really do think alike. Can you manage if we begin at a run?”

“Yes.”

“I meant with your wounded shoulder.”

“My legs are well.”

“Right.” At the mention of her legs, his eyes roamed, unbidden, down her body and up again. He cleared his throat and looked away. “Let’s put a little distance behind us, several blocks or so. Then it should be safe to stay parallel to the water but not in the full view of the bank.”

He shoved off in that direction at a trot, and she darted behind him. He’d planned to lope for a quarter hour and then allow her walk, but she kept an enviable pace, and he felt safe enough to slow down to a walk after just two blocks. They breathed in unison, deep, hard breaths. Bryson stole a look. He wondered again about her age.

Her face, furrowed now with fear and fatigue, was quite pretty—beautiful even. It was not often he saw a female with unbound hair. Not even a braid or a pin to keep it back from her face. Red-gold waves fell down her back like a cape. He fought the irrational urge to reach out and tuck it behind her ear.

He cleared his throat. “Do you have a name?” he asked.

She shook her head, a barely perceptible shake. She returned her focus to the road.

“Not the talkative sort, are you?” He nodded. “I understand. What a devil of a night this has been. Unfortunately, I am accustomed to these sorts of misadventures. I can frequently be found crawling out of windows or leaping from speeding carriages. It becomes old hat, I’m afraid.”

She looked at him, and he gestured toward a street to their left.

“My father,” he provided.

When she said nothing, he felt compelled to explain. “He has a bad habit of subjecting me to his diversions by force, which, unfortunately, seem to become more unpleasant, not to mention more illegal, by the year. The truth is, it amuses him to humiliate me.”

They turned down a long, curved thoroughfare with no torchlight, and he glanced at her again. One thing was certain, she’d never jeopardize their escape by making any sort of fuss. Even her footfalls were quiet on the gravel street. The hem of her shift barely rustled as she took two steps to his one.

“I’m called Bryson,” he said after a moment. “Bryson Courtland. One day, God willing, I shall be Viscount Rainsleigh. My father is the viscount now, unfortunately.”

Bloody hell but that was chatty. He told himself that he’d heard this about prostitutes. That you could say things to them that you wouldn’t ordinarily risk with someone you would see again.

“Likely you’ve never heard of him,” he continued darkly. “This is because my father makes no effort toward the title. Nor does he mind the property. His reputation precedes him, but only with enraged creditors, gamblers, addicts.” He looked at her and then asked, inspired, “Or perhaps you do know him?”

“I am not in acquaintance of your father, sir.”

Sir.

No one called him that, although, rightfully, they should. But there were very few servants left at Rossmore Court—servants had to be paid—and he kept to himself at school.

They heard a carriage in the distance, thank God. He needed a reason to stop talking. It was probably nothing, but he held up a hand to stay her. They ducked around a corner and collapsed against the side of a building. Making no sound, he spidered his fingers across the brick until he found her hand, and he covered it with his own. The conveyance rolled past without incident, and he said, “Harmless,” and waved her back to the walk.

“Will your father be cross that you left him behind?” she whispered.

“I don’t really care,” he said with a sigh. “My main concern is getting back to school. My holiday, such that it was, is over, and I must be to Cambridge by Monday. After tonight, I’d say that going home would be imprudent. But I will need my belongings. If I don’t send for them, my father will sell them. Eventually I will go back, because I look after my brother, God save him.”

A cat skittered in front of them and disappeared under a rise of steps. He watched her follow it with her eyes. “And what will you do? What business do you have in Mayfair?”

“I have an aunt there—in Grosvenor Square,” she said.

“I wish I had an aunt in Grosvenor Square.” He looked right and left and crossed the street, motioning for her to follow. “Will there be a doctor for your shoulder? In the care of your aunt?”

“Yes.”

“And, perhaps….Honest employ?”

They rounded a corner before she could reply, and there it was. Blackfriars Bridge. It lay across the inky water of the Thames like an outstretched arm.

“Is this it?” she asked.

“It is.” He squinted through the mist rising from the river at the bridge. “Hmmm. More traffic than I had hoped this time of night, but we needn’t worry. My father would never find it worth his trouble to come after me now.” He scanned the bridge. “These are farmers mostly, headed to market . . . setting up stalls for the morning crush. We’ll keep our heads down. Make quick work of it. We can easily be on the other side in a quarter hour.”

She nodded but held back, waiting for him to lead.

“Right,” he said, and he shoved off the ledge toward the bridge. She hurried after him and then surprised him by grabbing his hand. Her grip was warm and firm and . . . familiar, as if he’d been holding her hand all of his life. He was unaccustomed to being touched by anyone and certainly not by a girl, but it was surprisingly easy to clasp back, to gently lead her. He grew surer of their safety and direction with every step.

She let out a shaky sigh when they descended the steps on the opposite bank, and he said, “It won’t be far now,” but he didn’t let go of her hand. The sun was beginning to warm the horizon, and birds called from deep inside the leafy canopy of the street. They walked toward Westminster. He held her hand.

When they neared Green Park, he said, “It will be daylight soon. People will see us . . . servants making preparations for the day. Grosvenor Square is just a handful of blocks away. I wouldn’t want you to appear suspicious to the other staff who work with your aunt.” He cleared his throat. “That is, the focus should be on your wound and reunion and not who the devil I may be.”

She dropped his hand, just like that. He looked down at it his empty palm, fighting the urge to take a step closer.

“I should like to walk alone from here,” she said, staring across the park.

“I didn’t mean to dismiss you,” he said. Now he took the closer step. “I have every intention of seeing you the rest of the way. I’m simply trying to…” he trailed off, frustrated. He had no idea what he was trying to do.

“I know the way,” she said. “You have been more than kind. You needn’t trouble yourself. As you said, you must find your way back to school.”

“Yes,” he agreed, a reflex.

She backed away from him. “Thank you so much. Godspeed to you.”

And then she turned her back and jogged a diagonal path across the park.

“May I—” he called after her, but then he stopped.

He ran a few steps to be heard and started again. “I will inquire after your health on my next holiday. I should like to know that you’ve been looked after.”

“Please do not follow me,” she called over her shoulder.

“Of course,” he mumbled to himself, watching as she grew smaller and smaller in the distance. When a milk cart passed between her silhouette and his view, he lost sight of her altogether.

She was gone.

~ End of Excerpt ~

Order your copy of The Virgin and the Viscount

→ As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. I also may use affiliate links elsewhere in my site.