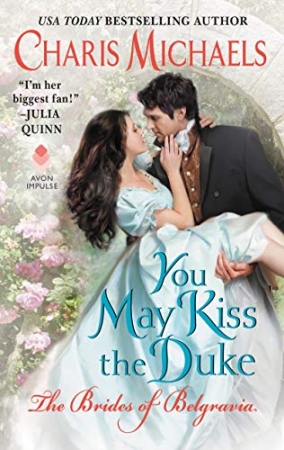

USA Today Bestselling Romance Author

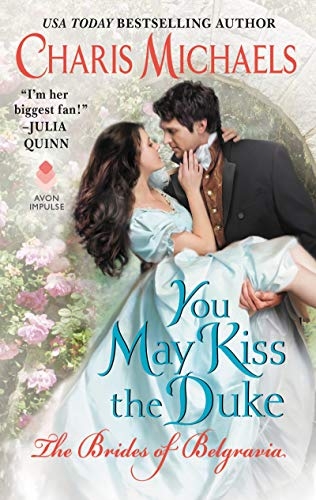

You May Kiss the Duke

Book 3 of the Brides of Belgravia Series

A MARRIAGE OF CONVENIENCE

Against her better judgement, spirited beauty Sabine Noble agrees to speedily marry a stranger who can remove her from the home of an abusive uncle. The union allows her to relocate to London and start a new life writing travel guides and enjoying the city on her own terms.

A DOWRY WITH NO EXPECTATIONS

Sea Captain Jon Stoker has no desire to be a husband, but Sabine’s offer of a commitment-free marriage and a hefty dowry is hard to refuse. After he delivers Sabine from her violent uncle, the deal allows Stoker to say good-bye and sail away.

A CHANCE RESCUE

When Stoker’s travels put him in harm’s way, neither dowry nor freedom can save him. His unconscious body is returned to England, and a chance discovery by his estranged wife rescues him from the morgue. Sabine is uncertain of her responsibilities to the unconscious husband she barely knows, but she begins the reluctant job of nursing him back to health.

A RECOVERY OF THE HEART

In the private confines of Sabine’s bedroom, the estranged husband and wife reckon with the attraction that has been there all along and the new, hot-sparking desire. And when Stoker has recovered and Sabine takes revenge on her dangerous uncle, they realize that attraction and desire have evolved into love.

Connected Books

You May Kiss the Duke

Book 3 of the Brides of Belgravia Series

The full series reading order is as follows:

- Book 1: Any Groom Will Do

- Book 2: All Dressed in White

- Book 3: You May Kiss the Duke

Enjoy an Excerpt

You May Kiss the Duke

Buy your copy →

Read or write reviews on Goodreads →

. . . . . .

Prologue

October 1830

Pixham, Surrey

Before

Sabine Noble agreed to marry because of a cupboard.

It was a cedar cupboard, built into the wall of the green salon, formerly used to store table linens and silver. Now the linens were draped over furniture, and the silver had been long sold. The cupboard sat empty, a three-foot-by-three-foot space, secured from the outside with a wooden peg.

The cupboard represented a new level of humiliation for Sabine. She couldn’t explain the cupboard away with a lie about a fall from her horse or an accident on the stairs; and dark, tight spaces elicited a particular sort of hysteria.

Perhaps it was understandable that Sabine was not herself when she was finally, unexpectedly, released from the cupboard after forty-five terrible minutes of dark, airless indignity. Perhaps the cupboard—or rather freedom from the cupboard—was the perfect storm of relief and opportunity and panicked going-along.

Perhaps she wouldn’t have agreed to the marriage if her uncle hadn’t locked her in the cupboard on the first day Jon Stoker came to call, but he did lock her in, and this is the story of what came after.

Jon Stoker agreed to marry because saving women had become a rather burdensome lifelong habit, and Sabine Noble was meant to be his last hurrah.

Stoker had turned up to Park Lodge that day, uninvited and unknown to Sabine or her uncle, due to an advertisement that Sabine and her friends had posted in London. The advert offered the girls’ dowries in exchange for marriages of convenience. The girls hoped to gain access to London after speedy marriages to sailors who would be rarely, if ever, at home.

Stoker wanted no part of it, despite the unexplained enthusiasm of his business partners. He’d called that day for no other reason than to tell her that he’d been volunteered out of turn; marriage was not in his future, thank you, but no.

He was met on the doorstep by an impervious old man who tried immediately to send him away. Stoker heard shouts of distress from inside, banging, muffled cries for help, and he forgot the advertisement and stepped around the sputtering old man to follow the sounds.

For ten minutes Stoker prowled the ground floor, his ear cocked to the cries, while the man threatened eviction and the sheriff. Stoker ignored him and located the source of the noise in a back parlor. A cupboard, its hinges rattling with blows from inside. He removed the lock and whipped the doors open and Sabine Noble tumbled out, gasping for air.

Jon Stoker’s life was forever changed.

Sabine recovered with the speed of a woman prepared for the next terrible blow. She darted behind a chair, gasped for breath, and shook her hair from her eyes. When she looked up, she saw a stranger shoving her uncle into the very cupboard from which she had just been released.

“Duck,” the stranger ordered Sir Dryden, his hand pressing the older man’s head. “Duck,” he said, louder. Sir Dryden ducked, the door was slammed shut, and the stranger turned calmly. Sabine gripped the back of the chair.

“I’m Jon Stoker,” the stranger said.

Sabine nodded cautiously, too breathless and hoarse to speak. She touched a hand to her swollen eye. She tasted blood on her lip. He watched with solemn patience, no wincing, no reaching out, no bellowing for a maid. He waited.

“Mr. Stoker,” she finally repeated, but she thought, Who?

When realization dawned, it was as swift and painful as Sir Dryden’s backhand.

No, she thought, disbelieving. Her hands slid from the chair and she took two steps back.

No.

Not that Jon Stoker. Not—

Jon Stoker was the name of the man who had answered the advertisement posted by her friends. The advertisement for a husband.

Jon Stoker, her friend Willow had told her, had been the applicant most suited for Sabine.

Jon Stoker could only be here for one purpose—a proposal. To her. Today. On this of all days. As her face swelled and her lip bled. As her uncle began to slowly knock a bony knuckle against the inside of the cupboard door.

Surely not.

Sabine closed her eyes, willing herself to disappear. She willed Jon Stoker to disappear. She willed Sir Dryden to hell and beyond.

Stoker cleared his throat. “This man”—he pointed to the locked cupboard—“is a problem. Obviously.”

This man—

Sabine did not answer, and she wouldn’t answer. She wouldn’t look at him, or make excuses, or thank him, despite the fact that he deserved her gratitude. And she certainly would not marry him. The advertisement had been her friends’ mad scheme. Sabine had gone along because she’d never thought it would come to anything.

She turned and began to weave through the furniture to the parlor door.

“Is there somewhere we can go?” he called after her. “To speak?”

Sabine picked up speed. She darted through the door, bustling down the corridor.

Bustling? No, she was fleeing and Sabine never fled. Her face burned with fresh shame. Was it not enough to suffer the humiliation of being beaten by a tyrant uncle and released from captivity in her own home? Must she also be chased?

“I’d like to speak with you,” Jon Stoker called, striding behind her. “About the advert.”

Sabine missed a step but kept moving.

The advert, the advert. Sabine swore in her head.

Her friend Willow had proposed the advertisement on a day like today, when Sabine harbored a broken rib and her future with Sir Dryden had seemed like certain death. Sabine had acquiesced, and now someone named Jon Stoker was here, witnessing one of the greatest humiliations of her life, and unbelievably, she did not hate him. Yet.

“I am interested in the advertised . . . arrangement?” Jon Stoker said from behind her. It came out like a question. “The offer is still on, I presume?”

Sabine stopped short and grabbed the wall to keep from pitching forward.

She glanced over her shoulder at the tall, dark man. She thought, He must be as desperate as I am.

Jon Stoker asked, “You are captive to this man? He is your father?”

If ever there was a statement to draw her out, it was this. “Absolutely not,” she said. “Sir Dryden is my uncle.”

“Where is your father?”

“Dead. Six months. Sir Dryden is his elder brother. His less accomplished, avaricious, cruel, and petty elder brother.”

“Your father’s will stipulated that control should go to this brother?”

“There was no proper will. My father died unexpectedly. His heart seized up, they say.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Yes. We are all very sorry.”

“How many family members remain here?”

“My mother, myself, a handful of devoted servants who refuse to leave us. However, Sir Dryden’s rages are reserved only for me.”

“For how long?”

Now Sabine paused. She was not in the habit of answering personal questions from strange men. As a rule, she did not answer personal questions from anyone or speak to strange men at all. But Jon Stoker was so incredibly matter-of-fact, so level. She could not have tolerated hysteria or bluster. Sabine thrived on calm, and Jon Stoker appeared the very soul of calmness.

And, best of all, he didn’t ask why.

Why did he lock you in the cupboard?

What did you do to invite a blackened eye or a bloody lip?

He did not ask.

The answer was, she’d refused to serve Dryden’s cream tea. He’d proclaimed that a proper lady should serve the master of her house, and she’d said, Pour your own bloody tea. And off they went. To blows. To the cupboard.

“My father died in February,” Sabine said. “Dryden installed himself after the funeral. He and I have been at odds since then.”

“At odds?” Stoker choked.

Sabine touched her swelling eye. “We do not get on.”

He allowed this incredible understatement to resound between them. Finally, he said, “Is this the worst of it?”

“There was a broken rib, I believe. Or two.” Sabine hadn’t realized the relief of actually telling someone. Especially someone she did not know and who would leave here in five minutes. She’d hid the worst of the abuse from her mother and her friends. She was so very ashamed—and what could they do? The helplessness was as terrible as the pain.

Yet, here she stood, telling this man.

“But his attacks,” asked Stoker, “do not extend to—?” He stopped, ran a hand on his neck, and began again. “That is, he does not . . . ?” Another pause. His flat tone had taken on a stratum of something harder, something decidedly less calm.

She shook her head. No. Thank God. Not that.

Stoker nodded and looked away. He took a deep breath. “You cannot remain here,” he said.

Sabine could not know it, but Jon Stoker had rescued hundreds of girls over the years—not because he’d married them, but because he’d beaten down doors or stabbed oppressive men or stolen them way under the cover of night.

Some said he’d been born a hero; others said he fought in memory of his desperate mother. Stoker said he was in the wrong place at the right time. All too often.

Regardless of the reason, regardless of their prisons, he always said these same words. You cannot remain here. It was routine.

Sabine raised her chin. “I am in the process of cataloging my father’s legacy. He was a cartographer of some merit, and he was scheduled to publish a collective of maps when he died. There are surveys and drawings and text—much of it out of order, all of it unfinished. There are apprentices living here at Park Lodge to curate the work, but I had taken the lead since his death. And my mother is not well. We are lucky to have a devoted caregiver, but her health is tenuous at best.”

“And how effective are you at these endeavors when you are under the dominion of this man?” Stoker asked.

Sabine looked down at her hand. A bruise shined from her smallest finger, a remnant of the week prior, when Sir Dryden had come upon her at the drafting table and pressed a paperweight into her hand.

“The truth is,” she said, “I cause my mother fresh grief the longer I remain. She cannot bear to see me hurt.”

“This is why you advertised your dowry?”

Sabine looked at him. There were reasons, and then there were fantasies made up by well-meaning friends. The advert had been a fantastical, made-up thing.

“My friends engineered the advert,” she said. “I have no wish to marry.”

“I have no wish to marry,” countered Stoker.

It was not what she expected him to say. He’d been asking for ten minutes if the advertised proposal was still on. He stood five feet away, feet planted. Leaving seemed the furthest thing from his mind. He studied her as if she knew the solution to a problem that could change both of their lives.

For the first time, she allowed herself to look at this man, to really look at him. He was large, of course. Sir Dryden had not fought him because Jon Stoker was large and her uncle was a coward. He wasn’t simply tall, however. Stoker was broad-shouldered, with a substantial chest, flat middle, and long, thick legs. He had the physique of a farmer, someone who lifted heavy things, who plowed and chopped. His face was tan and weathered. He was older than she was but not so very old, ten years beyond her own twenty-three years, perhaps? He had black hair, rather like a pirate.

A farmer pirate?

Later Sabine would scold herself for standing before him, wounded and embarrassed, and inventing the label farmer pirate. Vigilante stonemason and blacksmith warrior also came to mind. Had she hit her head in the cupboard?

Stoker broke the silence. “What is your reason?”

“I beg your pardon?” Only a lunatic could follow this conversation.

“Your reason for not wanting to marry?”

“Oh. That. Well, I’ve realized in the past six months that I’ve no wish to live under the dominion of any man. Not ever. And I am very occupied with my father’s legacy, as I’ve said. I haven’t the time to tend to a husband. Or the desire.”

He nodded, and she asked him the same question. “What is your reason?”

He paused, studying her, almost as if he weighed the benefits of answering.

Sabine crossed her arms over her chest. Oh, you will answer. It’s only fair.

He cleared his throat. “Marriage involves another person, doesn’t it? The combination of two lives? I’m certain that my life is not suitable for anyone but myself. I would not inflict it on an unsuspecting woman.”

This made her laugh. “How dashingly cryptic, but hardly an answer. Why not inflict this life?”

Another long stare. “Very well,” he said. “To begin, I was born in a brothel.”

Now he crossed his arms over his chest. His expression said, That should shut you up.

“And I,” countered Sabine, “just emerged from a locked cupboard. My father is dead. My mother is going blind. My uncle is a sadistic tyrant from whom I cannot seem to escape. This is not a conversation for the faint of heart.”

He rolled his shoulders. “Right. Well, I was born a bastard, to a mother who could scarcely care for herself. I was brought up in the streets. I have seen more devastation than you can imagine. I have since acquired some means, and by some miracle I have been educated. I have an import business with two partners. I own a ship. I have sailed the world. But matrimony is not like money or knowledge or travel, is it? You don’t simply earn marriage and use it to your advantage. Marriage will convene all of my terrible history on another person.”

“And what if the other person does not wish to convene her life with yours? What if she wishes marriage in only a legal sense?”

He looked confused. “Every woman wants to convene.”

“I don’t.”

He cocked his chin.

“Can you not see my face?” she went on. “Do you recall the locked box from where you, only moments ago, released me? I shall never, ever, put myself in a position of obligation or subjugation to a man again. Marriage is a union of trust, and trust, for me, is gone. But I would do it for the freedom of the thing—that is, I would possibly do it. As a way out. If the circumstances were correct.”

If she was to pinpoint a moment in the conversation when she went from resisting this madcap scheme to actively campaigning for it, it was now.

The words I have no wish to marry had allowed her to reconsider.

Jon Stoker said, “But a traditional marriage to a kind man could deliver you from your situation.”

“My uncle appeared kind before he backhanded me within days of my father’s funeral. Would marriage to a loving girl vanquish all of your demons?”

“I don’t have de—”

“I don’t want to know, actually,” she said, holding out her hand. “Forgive me, but I believe we might have reached some common ground. I want no part of a traditional union with any man. I could not be more serious about not wanting it. However, I would consider an alternative.”

“And so the advert was meant to . . . ?”

“The advert was an aspirational daydream engineered by my friends. I never expected it to elicit someone like you.” She looked him boldly up and down.

“And you know what I’m like, do you?”

“I know you released me from the cupboard without ceremony. I know you have been measured and steady in a very strange moment. I know you need my £15,000 dowry—you would not have answered the advert if you did not.”

“These are but a fraction of the things to know about me.”

She continued as if she hadn’t heard. “And if you have no wish to marry, and I have no wish to marry, then we could, in theory, marry in name only and part ways. I will go to London with my friends and enjoy the freedom of a married woman. You may . . . go wherever you will go and do whatever you do. We shall live separate lives. Oh my God, this might actually work.” Sabine felt a little breathless. The terror and humiliation of her uncle’s dominion had been so oppressive, the possibility of some deliverance, any deliverance, felt like a gag had been removed from her mouth.

“You cannot remain here,” he repeated.

It was not a refusal and Sabine forged ahead. “Swear to me now,” she stipulated, “that you will never raise a hand in violence to me, not ever. That is, on the very rare occasion that we should see each other. And I do mean very rare. Once every five years.”

“I do not strike women,” he said.

“And swear to me that, if we marry, you will take my dowry and go, leave me in peace. That we shall carry on separate existences in separate parts of the world. That we will have no sway on the life that the other builds.”

Sabine’s heart had begun to pound like she was running a race. This conversation felt very much like a race. They had begun to walk, and then he walked faster, and then she walked faster, and then he had begun to run, so she began to run, and now they were both sprinting side by side, trying to keep up.

“I swear,” Jon Stoker said slowly, and Sabine thought, My God, what if this actually works?

. . . . . .

It had been a true statement; Stoker did not strike women. Also true, she could not remain here. But he’d lost track of whether he was trying to convince her of something, or she was trying to convince him.

You will save her by marrying her, he thought.

She will die if you do not.

“This is madness,” she said, letting out a little laugh, and she turned away. Stoker felt something like panic rise in his throat.

“I will take your dowry and go,” he rushed to say. “You have my word.”

She turned back. “You require the dowry money so badly?”

This, he elected not to answer.

She continued, “Or has your misspent life treated you with such callousness, you have no aspirations to real happiness? You can simply marry anyone, no bearing on your future. It simply won’t matter.”

Stoker was not accustomed to women weighing his aspirations or his happiness. He also was not accustomed to lying. He was many regrettable things, but never dishonest. He opened his mouth to say, I don’t require the money, not in the way my partners do, but the look on her face caused him to close it. He paused.

Stoker and his partners were embarking on an import voyage to bring guano fertilizer to the farms of England. It was new and untried and potentially a windfall beyond their wildest imaginings, but they could benefit from some financing to raise a crew and provision. They’d considered the girls’ advertisement because their dowries would finance the first expedition and then some.

That is, his partners had considered the girls’ advertisements. His partner Joseph had fallen into something like love-at-first-sight with his potential bride. And Cassin really did need the money.

Stoker was not in love nor destitute. But what if he married as a way to end the exhausting business of saving people?

No more Stoker as hero, Stoker as savior, Stoker as someone else’s deliverance from . . . whatever.

The sacrifice of marrying Sabine Noble—of marrying anyone at all—would be so great, he could retire.

After her, he could walk away.

It was helpful that the marriage described by Sabine was meant to be completely detached, with oceans between their lives, and wholesale unaccountability. It was really no marriage at all, except by name.

Stoker took a deep breath. He looked her over once again, and she raised up to her full height. She hiked her chin. He felt something twitch and sink inside his chest, like sand dropping into a hole on the beach.

This was a woman who had choices, he thought. She could have her pick of men. The dowry she advertised was significant and her beauty was dark and rare and, if he was being honest, took his breath away. Coal-black hair, long lashes that shielded emerald eyes, perfect nose, perfect mouth—perfect everywhere. Even beaten by her uncle, even desperate, he could not look away.

“Mr. Stoker?” Sabine prompted. “Why would you marry a stranger, if you’ve sworn never to marry?”

“For the dowry money,” he heard himself say. He would blame it on the money but know it was one final act of altruism for a pretty girl in a bad situation.

“Right,” she said, her voice tentative but also official. “You will do it for the money, and I will do it to leave Sir Dryden. I suppose it’s all settled.” She took two steps back.

“Do you have to gain your uncle’s permission to leave home and marry? Does he control the dowry?”

She shook her head. “No. My father prepared the dowry years ago, thank God. Sir Dryden may remain locked in the cupboard until he rots, for all it would affect me.”

“Are you safe from him tonight? Eventually, a servant will release him.”

She shrugged. “I think we should do it as quickly as we can. I can go to my friend Willow’s aunt’s house in Belgravia. This has been Willow’s plan. Let me speak to my mother. She has a devoted lady’s maid who will see to her care when I go. She will miss me but be relieved that I am free of him.”

“Right,” Stoker said, working to keep his voice normal. “We shall do it as quickly as we can.”

. . . . . .

Chapter One

August 1834

London, England

Four years later

Some eight miles outside London, rising from the banks of the River Thames, Greenwich is a sprawling, leafy antidote to the crush of the city.

This former royal retreat is the first glimpse by which seaborne travelers view London, but landlocked visitors may explore it in person.

The royal palaces, now recommissioned for use by the Royal Navy, are open to the public and home to hundreds of maritime paintings. The so-called “Painted Hall” dazzles visitors with a floor-to-ceiling mural of ocean squalls, sea serpents, and nude sailors in repose.

Admission 1d. Royal Palaces closed Tuesdays and Sundays.

—from A Noble Guide to London by Sabine

Sabine Noble reread her last line and contemplated the prudence of “nude sailors in repose.”

Too provocative?

Potentially, but she’d counted no fewer than thirty-five naked seamen in the overwrought mural, far too many not to mention. Sabine’s travel guides had become best-sellers due in no small part to her plain speaking, not to mention her instinct for attractions that would stand out to rural visitors, in particular. Naked sailors fell well within this category.

Sabine left the phrase in and roughed out the sketch that would become the map that accompanied her description of Greenwich. The descriptions amused Sabine, but her true passion was the maps. Part illustration, part functional guide, Sabine filled each Noble Guide to London with eye-popping cartography. Not simply maps, but colorful works of art that told a story about each of London’s many boroughs and neighborhoods.

“I think we have it, Bridget,” Sabine said to the dog resting at her feet. “Measure twice, sketch until it leaps from the page.”

The dog, a patchy, one-eared mongrel with a perpetually bared incisor, scrambled to her feet and stabbed her nose to the air, searching for threat. Few things triggered the dog’s vigilance like the words I think we have it.

I think we have it meant the boring, civilized portion of their day was over, and the excitement would, at long last, commence. Little of interest happened while they surveyed serene parks and hushed museums, but what came after could be very exciting, indeed.

Packing away her drafting kit, Sabine turned her back on the stately order of Greenwich and squinted at the River Thames. Downstream, not a quarter mile away, bobbed the hulking, three-deck warship known as the Dreadnought. The boat had been decommissioned in 1831 and anchored in Greenwich to serve as England’s floating maritime hospital. The ship took in gravely ill English seamen who had made their way to home to recover (or die) on its bed-lined decks.

Sabine had been mindful not to mention the Dreadnought in the Noble Guide’s entry on Greenwich. Famous warship or not, a hospital was no draw for holiday seekers. Visitors to the Dreadnought came to call on the bedside of sick relations, not tour the sights.

Today, if she was lucky, Sabine and her dog would call on ten or eleven sick relations—or rather, she would feign some relationship to a dozen sick sailors on board.

“You must pretend to be very excited to see these men,” Sabine told Bridget, striding down the riverbank to the looming, ark-like figure of the Dreadnought. “I’ve made an actual script today, loose though it may be. And you are the star.”

Too much advanced planning, Sabine had learned, was a threat to flexibility, and flexibility was what allowed her to drift in and out of places that a lady would ordinarily never drift. She had become a rather accomplished snoop, which fit ever so nicely with her other identity as bestselling travel writer. She could pass a morning mapping a given area, making notes about statues and Norman churches, and then devote the afternoon to infiltrating a nearby dark alley or, in this case, a looming hospital ship. If she was detained or challenged, her alibi was the true story of her own life. She was the author of a popular travel guide, and she was in the area for research.

Sabine’s father, the famous explorer Nevil Bertrand Noble, had enjoyed the dual role of adventurer and cartographer, so travel writer and snoop felt quite natural to Sabine, if considerably less esteemed. But Sabine couldn’t care less about esteem. She wanted only two things: revenge against her uncle and to finally return home.

She’d arrived in London four years ago from her home in Surrey so very angry, reeling from what had become of her life. Her father had died and her uncle had moved into their family estate and turned on her. Touring the streets of the city had soothed her. She had walked and walked and walked, tears burning her eyes, thoughts racing, railing at the injustice of it all. But also making sketches, each one a little more detailed than the next, of the neighborhoods and boroughs she toured. Soon A Noble Guide to London was born.

Her father’s map engraver agreed to publish the first installment, and they had invoked Nevil’s reputation to promote the book. In no time at all, readers were clamoring for Sabine’s clever writing and beautiful maps. By the second installment, bookshops were doing a booming business. By the third, the engraver was begging her to feature every borough and attraction of London in new installments of her Noble Guide.

Sabine had complied, choosing parts of town that would be of most interest to tourists. For weeks, she had prowled London’s landmarks and hidden treasures, until one day, quite by chance, she crossed paths with one of her father’s former apprentices. The young man had been a favorite of the family, and he and Sabine took tea in a café to commiserate about their lives since the great explorer’s death.

Amid the pleasantries and remembrances, the young man bemoaned the fact that Sabine’s uncle had cut ties with all of her father’s students and turned them out of the student cottage at Park Lodge.

“But for what reason would Dryden dismiss you?” she had asked incredulously. “The engraver was paying your stipend, not Dryden. And when Papa’s final maps are published, the estate will enjoy the profits. Your work would be a windfall for my cursed uncle.”

The apprentice had shrugged. “Cannot say, madam, but he was quite emphatic about it. Between you and me, we students believe he has some alternate plan for the maps. He asked for every sketch, every note, every slip of parchment from our desks. He searched the cottage and our belongings, making sure we stole away with nothing. The same morning that servants carried every folio and map to your father’s old library, new locks were installed. I was in the middle of a measurement when they swept through, and they wouldn’t permit me to finish the line.”

“But it makes no sense to stop work that would eventually bring more money,” Sabine had said. “And Sir Dryden had no real interest in Papa’s work.”

The student had shrugged. “Before we left, I saw that Sir Dryden had guests to the library, a crowd of men in three carriages. He herded them inside and slammed the door.”

“What manner of guests?” Sabine had asked.

Another shrug. “Older gentlemen. No one I’d seen before. No one from the world of cartography or engraving, I’ll tell you that.”

Sabine had left the encounter reeling. She’d raged at the sky and complained to her friends and walked the streets of London for half a day. Ultimately, she’d written to her lone, reliable source at Park Lodge, the longtime lady’s maid of her mother, a woman called May. Sabine asked specifically about new guests to Park Lodge and the eviction of her father’s students. May had dashed off a quick and detailed reply—names, dates, snatches of conversation overheard from the dining room—and Sabine’s search for evidence against her uncle had begun.

Why were her father’s students dismissed? What would become of their work? Who were these men, visiting Sir Dryden? How often did they turn up? What endeavor had Sir Dryden embarked upon using her father’s unpublished maps?

Beginning with names provided by her mother’s maid, Sabine began to nose around London for details. She hadn’t known precisely how she would exact revenge against Sir Dryden, but a clearer picture fell into place, clue by clue, every day. One man worked in shipping. Another, munitions. A third man was a chemist. Sabine vowed not to rest until she could determine Dryden’s business and return to Surrey to stop him.

Now she tossed a piece of bacon to Bridget and stared up at the Dreadnought. Somewhere inside were a dozen scurvy-ridden sailors who could fill in the gaps of her latest discovery. One of Dryden’s known associates was, she had discovered, a London-based shipper. The man himself had proven impossible to interview and his sailors were, unfortunately, almost always at sea. But Sabine had learned that this particular crew had contracted scurvy and were, at the moment, laid up on the hospital ship. Pity about their health, Sabine had thought, but also perfectly situated to answer some pointed questions about their employer and his expeditions.

“We must be very charming and lovely, Bridget,” Sabine reminded her dog, dropping another piece of bacon.

Bridget regarded every morsel of food as if it were her last, and she attacked the treat.

“You are not even trying, I see.” She shaded her eyes, staring at the ship.

Sabine’s capacity to beguile was nearly as limited as her dog’s, but unlike Bridget, her face and body tended to take over where flirtation failed. Green eyes and sable hair had that effect on men, whether she wanted it or not.

But who would they beguile if no one was on deck? The Dreadnought, which she knew to be packed with ailing sailors, looked abandoned in the bright afternoon heat. Sabine’s overt sweetness, already in short supply, was rapidly draining away. She ruffled her dog’s ears and scanned the area again. In the distance she spied a lone uniformed crewman slouched against the trunk of a tree. His rank was undistinguishable, but he was young. He was savoring a smoke with an expression that Sabine would best describe as blankness. Perfect.

“Hello?” Sabine called, approaching the man with a shy wave.

He looked up, sliding his gaze from the top of her hat, down her face and body, and up again. “Hello yourself,” he said hopefully.

Bridget growled deep in her throat. Sabine slapped a handful of skirt over the dog’s snout.

“Are you,” she asked, “a member of staff on the hospital ship?”

“Not for five minutes, I’m not,” the man said. “Break.”

“Oh, a break, of course. Good for you. But are you . . . a doctor?”

“Right, that’s me. Doctor.” He laughed. “Deck steward, more like. Who wants to know?”

“Steward? Oh, lovely, perhaps you can help me. Can you tell me how the patients are housed on the ship? That is, are they arranged by condition, or name, or perhaps the severity of their ailment?”

“Searching for a sweetheart, are you?”

Sabine shook her head vigorously. “Oh no, I’m a married woman.” About this detail, Sabine never pretended.

Her wedding ring was concealed by her glove, but she raised her left hand by force of habit.

After the obvious escape from her uncle, the two most useful things about Sabine’s hasty marriage to Jon Stoker were the wedding ring and the words I’m a married woman.

“My husband is a sea captain, in fact, but he is out of the country at the moment.”

The third most useful thing about her hasty marriage to Jon Stoker was that he was always, always, out of the country. In fact, the last time she’d seen him had been more than a year ago, and even then, their exchange had been limited to a few pleasantries in the street. They did trade letters on occasion. Their correspondence had not been planned, but Stoker had business with an impoverished aristocrat trying to claim a familial relation. It was an old duke trying to finagle a piece of Stoker’s growing fortune. At Stoker’s request, Sabine sent clippings about the old man from London papers and had even done some snooping around town. She described what she learned in letters and posted them to whatever foreign port Stoker was due to drop anchor.

“Married?” the steward repeated resentfully.

“Quite, but I’m seeking several members of a ship’s crew. They’re meant to be patients on the Dreadnought. They . . . they’d all succumbed to scurvy when they were admitted, I believe.”

“Which crew? You’ll have a list of their names, I hope?”

Sabine was a miserable liar, but she could hardly reveal that she had no such list. She knew only the name of the last ship on which they sailed.

“Actually, the crew is attached to this dog . . . ” she said gainfully, gesturing to Bridget. “She was their unofficial mascot on a particularly harrowing voyage. She has been left in my care while they recover. Scurvy, as I’ve said. It would bolster them to see her.”

The steward squinted at the dog, who, with narrowed eyes and bared teeth, looked like no mascot. In truth, the dog looked a little scurvy-ridden herself.

“Mascot, you say?” he said.

“Indeed. Beloved and sorely missed, I should think.”

“How did you come to mind her?”

“My brother was among the crew.”

And now the lie grew. Sabine spoke more quickly, trying to prevent the story from taking a life of its own. “He died at sea, sadly. But the crew members who survived left the dog in my care. I promised to bring her to visit.” She swallowed and added, “As my brother would have wanted.”

Sabine snapped her fingers, and Bridget reluctantly lowered herself into a dejected squat, sitting in a crooked approximation of docility. Sabine smiled a sad, wistful smile and batted her eyelashes.

To further distract, she added, “But what is the nature of your work as steward? Do you care for all the patients?” She fidgeted with the button on her glove, flashing the pale skin of her wrist.

He nodded. “All. Except the dead ones, of course.”

“The dead?” Sabine looked up.

To date, the investigation of her uncle had not brought her in the path of any dead bodies, and for that she was grateful. She’d been unsettled enough by the prospect of today’s sickly sailors. Corpses would be quite out of the question.

The sailor looked philosophical. “Aye, dead bodies. Getting on a hospital ship is no guarantee that you’ll get off a healthy man, is it? We stack the dead bodies in the ship’s hold.”

“How . . . efficient,” murmured Sabine. This conversation had taken an unpleasant turn for the worse.

The man shrugged. “Can’t rightly bury them at sea if the boat is docked. The River Thames is not the sea, is it?”

“No,” Sabine managed. She had no interest in the topic of dead bodies or their disposal.

She redirected. “But might your expertise extend to helping me gain access to the ship? I should very much like to locate these men.” She smiled her most beguiling smile. Bridget growled and she nudged the dog with her foot.

Ten minutes later Sabine and her dog were being admitted to the tidy, weatherworn gangplank of the hospital ship and directed to Deck Three.

. . . . . .

Jon Stoker was in hell.

At long last.

His body . . . on fire. His skin . . . burned away, limb by limb. His throat stung. His very hair was in flames.

His eyes . . . seared. Wouldn’t open. Couldn’t see. Couldn’t breathe.

Suffocation.

Needed to cough, needed to swallow.

Starving.

Thirsty.

Sick, so bloody sick.

Pain everywhere. Cold and hot all at once.

Call out? No.

Sit up? No.

Turn? No.

Draw breath? No, no, no.

Try.

Again.

Sleep.

Wake up. Still in hell.

Misery. Cold, burning, suffocating misery.

Now, a dog.

Barking. Barking so bloody loud. Hounds of hell?

And shouting. Deafening shouting. A woman, shouting in his burning ear. She took him by his burning arm. She pulled.

Pain. He was going to retch. So much pain.

Ceaseless barking. She would pull off his arm and feed it to the dogs.

“Stoker?! Jon Stoker! Stoker!?!?”

Profanity.

“Jon Stoker?!”

He was in hell, he thought, and the devil was a woman.

And she knew his bloody name.

~ End of Excerpt ~

Order your copy of You May Kiss the Duke

→ As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. I also may use affiliate links elsewhere in my site.