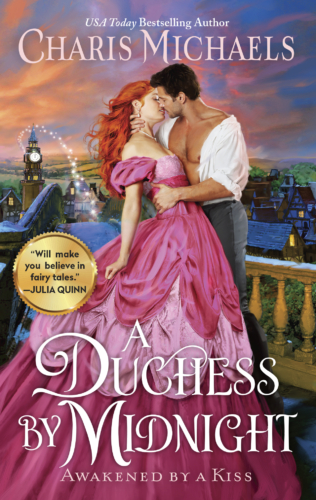

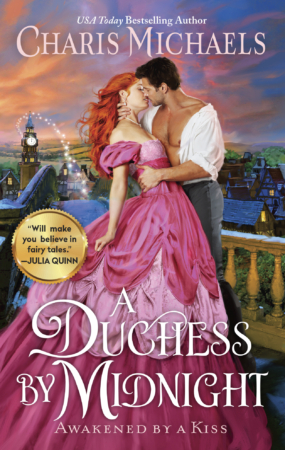

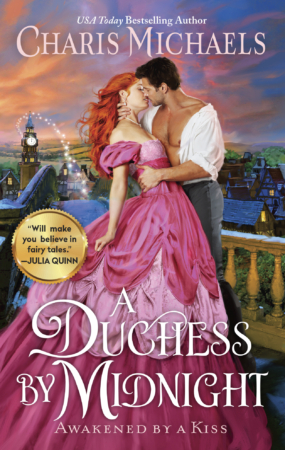

USA Today Bestselling Romance Author

A Duchess by Midnight

Book 3 of the Awakened by a Kiss Series

A Former Ugly Duckling…

Miss Drewsmina “Drew” Trelayne is a former awkward child and one-time wicked stepsister. Raised by a bitter, overbearing mother, Drew is all grown up and has made peace with her orange hair and bean-pole height. Her transformation has inspired her to open a finishing school that emphasizes inner beauty, capability, and confidence. But launching a school costs money so Drew begins with private clients who pay well and don’t ask questions.

A Reclusive Duke…

Ian Clayback, the Duke of Lachlan, lives alone on his Dorset estate, forced by scandal into a smuggler’s life. When his estranged sister arrives with her two daughters, he feels obligated to give the girls a proper Season. Venturing back to society could clear his name and provide his vagabond nieces with a better life. Who better to help than the striking Miss Trelayne?

A Midnight Kiss…

Affording Drew’s services isn’t a problem for Lachlan, but his growing desire for her is. As his nieces warm to her gentle charm, he is overwhelmed by her unique beauty and open manner. When they’re caught in a scandalous embrace, nothing short of marriage will save all of them from further scandal.

Can a marriage made in haste be love’s saving grace?

Connected Books

A Duchess by Midnight

Book 3 of the Awakened by a Kiss Series

The full series reading order is as follows:

- Book 1: A Duchess A Day

- Book 2: When You Wish Upon a Duke

- Book 3: A Duchess by Midnight

Enjoy an Excerpt

A Duchess by Midnight

Buy your copy →

Read or write reviews on Goodreads →

Jump to: Chapter Two

. . . . . .

Chapter One

Drewsmina Trelayne’s Rule of Style and Comportment #17: Never be carried away by one-sided conversations. Friends may not articulate boredom or shock, but prolonged silences speak for themselves. Babbling is for fountains or infants, not ladies.

Drewsmina Trelayne’s Rule of Style and Comportment #31: Live animals make terrible gifts.

Kew Palace

Richmond Upon Thames

October 1818

The antechamber to the Throne Room at Kew Palace was crowded that day, and Drewsmina Trelayne took stock.

To her right, a stern-faced woman in starched wool and a black cape. She stood close to the door and clutched a bulging satchel. A charity crusader, Drew guessed.

To her left, a military man in dress uniform and his fidgety aide-de-camp.

Near the window stood three nuns with a huddle of boys, likely orphans, or a choir, or an orphan choir.

Milling somewhere in the middle were two men of academic bent; one bearing a spinning piece of scientific equipment and the other a taxidermized specimen of a mouse.

There was also the elderly couple with the birdcage; and a rouged woman (opera singer or similar?), her maid, and two small dogs.

Finally, in the shadowy corner slouched a lone man. Tall, face averted, motionless, possibly asleep.

And then there was Drew herself, front and center, an enterprising young Woman of Business, on the cusp of both Enterprise and Business.

Inventorying the other callers had taken all of five minutes. Drew was bored but also anxious. It was not her first time to the palace.

Drew’s stepsister, Cynde, was married to Prince Adolphus, son of King George III. Although Adolphus was the king’s seventh son and tenth in line for the throne, he was a prince nonetheless. As such, he and Cynde made their home in Kew Palace. Typically, when Drew called on her stepsister, she was received in Cynde’s opulent private chambers.

The Throne Room, in contrast, was where the royal couple granted audiences to supplicants, charities, and petitioners, and Drew was here because today was not a social call. Today was business, the day Drew would be introduced to the new client who would change her life.

If said client turned up.

And if he could be persuaded.

If everything went exactly, perfectly according to the plan.

This plan, which until today existed only in theory, had been thrust into reality when Drew received a hasty note from Cynde last night.

Throne Room tomorrow, Drew. Can you please come? Arrive early and bide your time in the antechamber with the other callers (apologies—but the wait will be worth it, I hope!).

An old friend of Adolphus’s is meant to call. He’s in desperate need of help with twin girls in advance of their first Season. He’s called the Duke of Lachlan, very rich, but rather bumpkin-y or reclusive or socially inept or some such . . . cannot say for certain. He’s Cornish? Almost Cornish? Something to do with Cornwall?

But did I mention: twins! That’s two girls on whom you may work your magic, so come prepared to charm and convince, etc., etc. Follow my lead, alright?

Hoping this is the opportunity for which we’ve waited.

The note had made Drew a little breathless, and she was generally in full control of her breathing. Drew had been biding her time, waiting for exactly this sort of introduction for the better part of a year. The note had made her so hopeful, she sought out her brother-in-law, the tedious Lord Madewood, to ask him what he might know of a “nearly Cornish Duke of Lachlan.”

Madewood had welcomed her inquiry with his usual creepy aplomb; inviting her to his dark library, sprawling on a settee to pontificate for a half hour. In the end, the theatrics had been worth it. She’d learned that there was, indeed, a Duke of Lachlan. The dukedom was in Dorchester, very near to the Dorset coast. Three years ago, the duke had been at the center of a scandal that consumed the country. He’d shown promise in the House of Lords before the scandal but had since retreated to the ducal estate and hadn’t been heard from since.

“But what of twin daughters?” Drew had probed. “Girls he might wish to bring to London and launch into society?”

“Daughters?” Madewood had repeated speculatively. “I cannot say. His family was not discussed in the papers. Marrying off daughters would be very ambitious, indeed. No young woman, and especially no debutante, would benefit from association with such a recent controversy. I don’t care if her father is a duke.”

“Did the scandal involve some . . . indecency?” Drew ventured.

“Indecency? No,” assured Madewood, “it’s nothing like that. He was involved in a Luddite riot. Got a man killed and injured several others—a youth, I believe? That is, his mismanagement of unruly tenants…led to a riot…that killed a man…and injured the youth. Lachlan rabble-roused alongside his tenants, going so far as to join their ranks as if he was one of them. After whipping them into a fevered pitch, he played the turncoat and gave them up to the guard in Portsmouth.”

Drew considered this, weighing the risk of attaching herself to a family with a direct link to Luddite rioters. The so-called Luddites were skilled craftsmen—weavers or stockingers or lace makers and the like—angry that new textile mills were putting them out of work. Lives were lost, men were hanged.

Still, rabble-rousing and “mismanagement” didn’t sound so very bad, did it? Hardly ideal but it wasn’t as if the duke was a marauder, or a letch, or a highwayman. This was a situation with which Drew could do some real good—for the daughters, if nothing else. She had to begin somewhere.

“But perhaps enough time has passed,” suggested Drew hopefully, “and gossip about the riot will have died down? It was three years ago, did you say?”

“Yes, ’15. But, it was fuel to the fire for so many subsequent uprisings. It has not been forgotten, I assure you. Ask anyone about the Honiton Uprising and you’ll get an earful. There was outrage on every side. The villagers were furious that their landlord warned the garrison; and the regiment in Portsmouth was angry that a duke had aligned himself with peasants. Poor leadership, that’s what it was. He pitted the two sides against each other out of sport. Or he was out of his depth. Either way, he was too inexperienced and too arrogant.”

“Yes,” said Drew absently. She was thinking again of his daughters. What challenges would they face if their father was considered a rabble-rouser, turncoat, and instigator of civil unrest?

I can help them, she thought.

I can be of very great help to the lot of them.

Drewsmina Trelayne was in the business of—or rather, she would embark upon the business of—coaching young debutantes through their coming-out Season in London society. Her specialty was—or rather, would be—outsiders. Outcasts. So-called ugly ducklings. Girls who hovered on the margins of society life.

In short, exactly the type of girl that Drew herself had one time been.

She would specialize in snipe-prone, screechy girls; silly, giggling girls; or silent girls forgotten in the back of the room.

She would coach slouchy girls to stand up and quiet girls to speak up and chatty girls to pause and silly girls to listen. She would polish brashness and embolden shyness.

She would take on girls with scandal-shamed fathers who needed to rise above gossip and enjoy an untarnished debut.

She would do for her clients exactly what heartbreak and resilience had forced Drew to do for herself.

And she would charge a fee for the service, which would finally allow her to leave her miserable situation as a spinster sister in the home of Anastasia and the tedious Lord Madewood.

But first she required this client.

“Not very quick-like with the visitors, are they?” asked the old woman who stood beside Drew in the airless antechamber outside the Throne Room. She and her companion held a birdcage between them. The weight of the cage, not to mention the twelve or so Dartford warblers flapping about inside it, was heavy and unwieldy.

Drew had avoided the couple (in as much as anyone could be avoided in the tiny room) because it pained her to see any animal caged, especially birds, especially Dartford warblers. She’d developed a fondness for bird-watching these last five years, and she was familiar with the beautiful, reclusive warblers. They were partial to the dense, scrubby heathland in Surrey and not at all given to captivity.

Doubtless, the couple meant well. If Drew had to guess, they’d brought the birds as a gift. Later, when Drew and Cynde were alone, she could urge her stepsister to release them.

“We’ve been waiting an hour at least,” said the man holding the other side of the cage. His wife nodded indignantly.

“Well, that cannot be,” remarked the stern-looking charity woman. “Subjects are meant to call to the palace gate no sooner than a quarter to eleven. And it is currently a quarter past eleven. So you could not have been waiting an hour. If you’ll recall, I arrived to the palace gates before you lot. So. When Their Royal Highnesses Prince Adolphus and Princess Cynde admit the next caller, that caller is certain to be me.”

“If we’re splitting hairs on the matter,” declared one of the scientists, “I arrived before all of you.” He stroked his stuffed mouse.

“Surely you are mistaken, sir,” said the charity woman. “I was undeniably the first to arrive, not to mention my appointment has been scheduled with the prince’s secretary for weeks.”

“I am not mistaken,” the scientist replied, digging in his satchel for some proof.

Drew sighed and cast a glance around the small, dim room. Had the duke arrived? She saw no young women who might be the twins, so she assumed the girls would not be present. But the duke himself was meant to be a caller, just like her. Presumably he would be in the company of a wife. But surely a duke and duchess would not be subjected to the antechamber with orphans and birds in a cage?

She looked again. Perhaps he would be the officer? Although the military man looked very old, indeed. The twins in question would have to be granddaughters, if not great-granddaughters.

Or could Lachlan be one of the scientists? Also likely no.

Her gaze fell on the still, silent man slouching in the shadows. Theoretically, he could be a duke and theoretically he could be the correct age; but he could also be an undertaker who was ninety. Everything about him invited Drew to redirect her gaze…but curiosity caused her to glance back.

He stood so far from the lamps, she could make out little more than a voluminous overcoat, a face obscured by the brim of his hat, and tall boots. He shouldered against the wall, arms crossed, the posture of someone who was present in body but whose consciousness was far away.

Not that any of these details mattered, because he appeared too informal to be a friend of the prince’s. And again: dukes did not convene in antechambers with the masses. Lachlan would arrive by another door; he would not queue, nor would he slouch. The slouching, in particular, unnerved her, and Drew had enough reasons in her life to be unnerved. She had no wish to invite more.

“May I look at your birds?”

One of the boys had broken ranks from the nuns and stood peering inside the birdcage at the terrorized Dartford warblers.

“Not now, yeah?” whispered the owner of the birdcage.

In the same instant, her companion enthused, “Of course you can.”

“Are they sparrows?” asked the boy, suddenly accompanied by a second boy, then a third. Soon a semicircle of boys had formed around the birdcage.

“Keep back, if you please,” said the woman, trying to wrench the birdcage away. “These Dartford warblers are a gift to Prince Adolphus and Princess Cynde. They make a terrible mess when agitated, and I cleaned the cage this morning.”

“We won’t agitate them, madam,” assured the first boy, stepping closer. The others followed.

“There’s no harm in letting them look,” the man scolded gently. To the boys he said, “Admirers of birds, are you?”

Behind them, the charity woman had continued to grumble. “You’ll see. When the footman admits us, you will see. Guests are not shown in willy-nilly. This is a palace, after all.”

“And who asked you? That’s what I’d like to know,” said the old woman, distracted now from the birds.

“But would one of the birds sit on my finger?” asked the first boy. “If I stick it in?”

“He would bite it off,” assured the next boy.

The first boy ignored him and raised a pudgy finger to the cage, working it carefully between the bars. Above them, the owner of the birds quarreled with the charity crusader.

“Let me have a go,” demanded the second boy, and then a third. More fingers wiggled between the bars of the cage.

Looking back, Drew could identify this as the moment when everything went terribly, irrevocably wrong.

The cage wobbled. Thrashing, hysterical warblers flapped about, landing beaks and miniscule talons against the invading of fingers. The boys startled and yelped, jerking back their hands.

The collective jostling caused the door of the cage to unhinge and swing open. Within seconds, a dozen Dartford warblers, flying hell-bent for Surrey, launched from the cage and swarmed the antechamber.

Pandemonium filled the tiny room in a literal swarm. Birds, boys, yelping dogs; feathers rained down.

The owners of the birdcage leapt into action, trying to recover the birds with windmilling hands and flapping apron. Nuns crouched beneath their coifs and reached blindly for orphans. The boys scattered, leaping and swiping for the birds, hooting in delight. The opera singer embarked on a rolling scale of breathy screams. The other waiting callers ducked, shrank away, or swatted at the birds.

“Everyone, please,” Drew heard herself call, “keep calm. If we are still and quiet, the birds will settle.”

Calmness, it was clear, was as far away as Surrey. As Drew watched in horror, the terrified birds careened to the ceiling, swooped low, and collided with walls. The impact of each collision stunned them into disoriented flapping. One boy managed to capture a bird, and it lay gasping for air in his palm. The military officer swatted at a low-flying warbler with his newspaper, sending the little bird spiraling through the air like a leaf.

Drew’s eyes swam with angry tears. The birds hadn’t asked to be caged, nor carted to a palace antechamber, nor terrorized. The room was too small for them to flee and too spare for them to hide.

“Stop,” Drew tried again. “If we simply remain calm, the birds will not be so panicked. They can be—”

No one listened. Drew gaped about the room, helpless and angry. Now even the slouching man was joining the fray. He shoved from the wall and stalked through the chaos to the double doors that led to the corridor.

“Why not,” he was asking under his breath, “just open the bloody door…” he reached for the knob, “…and release the bloody beasts—”

“No, wait!” Drew gasped, lunging.

Drew caught his large, gloved hand just as it pulled the doorknob.

He looked up, and suddenly she could see his eyes. A chilling, piercing blue, the focal point of an exceedingly handsome face.

He was not, she now saw, ninety years old.

Nor was he an undertaker. Unless he was the most perfectly formed undertaker in the history of dead people.

He stared at her from beneath the brim of his hat in direct challenge. Yes? his expression asked.

Drew recovered and squeezed his hand to stay him. “No, please,” she said in a rush. Their faces were close, as close as two people sharing the same doorknob.

In that moment a Dartford warbler made a disoriented dive perilously close to her face. Drew yelped and jumped closer still.

“I’ll open the door,” the man explained slowly, plainly, as if speaking to a mad woman, “and the birds will fly through it.”

“No.” Drew shook her head violently.

An orphan boy bumped into her hip and she was shoved almost into his chest.

“No,” she repeated, righting herself. “If you please. If the warblers escape into the palace, they’ll become separated, they’ll fly mindlessly into far corners and never find their way out. They’ll die of starvation or be killed by staff. We’ll never recover them.”

“These…” he speculated, “are your birds?”

“No,” she said desperately, trying to make him understand. “Dartford warblers are not prone to domestication. The compassionate thing to do is to release them—but into the wild. Not into a palace.”

“And what do you propose?” Now an orphan crashed into him and clung. He used his free hand to lift the boy by his collar and set him back on course for the chaos in the room.

“If we can stop the panic and simply keep calm, the birds will settle. Then we might collect them one by one into the cage and release them properly. But we must all…” she looked with frustration at the room of revolving birds, shouting people, rampaging boys, and barking dogs, “…settle.”

“Right,” he said, following her gaze at the room. “Only mildly ambitious.”

Drew let out a distressed laugh. She couldn’t help herself. He was handsome, and he was funny. And she was holding his hand.

Drew’s heart beat very hard and heavy in her chest. It felt like an egg that contained something very new and wild trying to hatch out.

“Please, sir,” she said, swallowing, “I should like to try.”

Drew stared at him, shocked that he didn’t argue. He looked back with wintery eyes, and the egg of Drew’s heart thumped again. Finally, he gestured to the room with a go-on-then nod.

Drew blinked, snatched her hand away, and turned back to the room. It was a din of wild birds and shouting people and braying dogs.

“Stop!” Drew called, pitching her voice at a shout. “Please! Everyone, if we could keep calm, and allow the birds to find somewhere to light. Please!”

There was no response. Not a single glance. She opened her mouth to try again.

“What about…” the man shouted to her, “the window?”

He pointed to a small, high window that looked out onto a stone wall.

He continued, still shouting, “Would you permit me to release them through the window?”

“Yes, that would be perfect,” Drew shouted back. “If you can manage it.”

The man wound his way through scrambling people and careening birds. The window was high but he reached it with little effort.

“It’s painted shut!” he called to Drew.

“There’s no help for it!” she called back, halfway to him.

A boy darted in front of her and she caught him up by the wrist. “You must stop running,” she pleaded. Another boy followed and she caught him with the other hand. The boys pulled and squirmed against her hold, trying to rejoin the fray.

He pushed at the window again but it wouldn’t budge. Meanwhile, a diving warbler swooped low and almost collided with his head. He swore and ducked. He was readjusting his hat when a second bird hit him, this time in the ear.

“Are you hurt?” Drew called, releasing the boys. He ignored her as he scanned the room. His gaze lit on the smokey fire, and he reached for the metal poker propped on the hearth. Before she fully comprehended his intent, he took up the poker, thrust it through the window, and thrashed it around, shattering glass and breaking panes.

The commotion cut through the din in the room, and for a long second, all the shouts, arm waving, and barking fell silent.

The man continued his task, tracing the poker along the outline of the sill, knocking it clean. Shards of glass and splintered wood rained down. When he retracted the poker, only the open square remained. They immediately felt the morning chill and smelled the murky River Thames.

Silence took up gradual residence in the room, all sound filtered out the window. Everyone gaped from the absent panes, to the man, to the shattered glass at his boots.

In less than a minute, the first warbler seized freedom. A dozen flock-mates immediately followed, launching themselves from the terror of the small room into the free world. Feathers wafted to the ground. A dog whimpered. A breeze swung the door on the birdcage with a creak.

They recovered their voices all at once.

“By what right do you have, sir? I ask you—”

“How dare you, them birds belonged to—”

“Oy! Did you see it?”

The callers were angry and confused. Every comment was punctuated by glass crunching underfoot. The dog chorus resumed.

The man ignored them all, removed his hat, and pulled a gray feather from his ear. He wound his way through angry people to the doors to the Throne Room. He glared at the thick oak as if he could open it with his mind. He replaced his hat.

Drew watched him in disbelief. She’d encountered many people in her life. Well-meaning people, compassionate people, hardworking and capable people, but she could never remember anyone doing anything quite so demonstrative or dashing as this.

Without realizing she’d moved, she came to stand beside him.

“Thank you,” she said.

“I did it for the birds,” he said.

She chuckled. Another joke.

One of the boys skidded to a stop beside him, brandishing the fireplace poker like a sword. He ignored him.

“Any notion of how long they usually make us wait?” the man asked Drew.

“No.” She shook her head. She forced herself to stare at the door and not at him. “Shattering windows cannot hurt. If we mean to move things along.”

Another boy appeared, and the first boy began to jab at him with the poker. Two nuns descended and hauled them away. Behind them, the argument about order of admission had resumed.

“What are you in for?” the man asked Drew.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Why are you calling on the prince?”

“Oh,” said Drew, and she paused, trying to think of the best way to explain.

Later she would realize that the true damage of the day hadn’t happened when the birds were released or the window was broken.

Later she could see that the real damage of the day would happen now.

Now was when things went horribly, irrevocably wrong.

She said, “I’ve come to make the acquaintance of a potential client. Princess Cynde is my stepsister, and she is to make the introduction.”

And here, she should have stopped. He’d not asked for more details. She knew only that he was handsome and clever and together they had saved the warblers.

Unfortunately this was all she required to continue talking. Drew was a spinster and rather good at it, but she wasn’t dead. She’d excelled at style, and cleverness, and even confidence, but when it came to speaking to men, she was out of her depth. So very far out.

“I am in the business of turning out debutantes,” she said. “Not in the manner of a finishing school, not yet, but I provide a similar service. For private clients.”

The man beside her said nothing, but he slowly turned his head in her direction.

Now that she had his full attention, she felt compelled to add, “The potential client is a duke, actually. Lachlan, he’s called. A friend of the prince’s. He has twin girls that he wishes to bring out—that is, to launch into society for the next Season.”

The man narrowed his eyes. Was he intrigued? Fascinated? Her stomach flipped. She continued, “He is in need of help with the girls, and it is his business I’ve come to solicit. The duke’s. For his girls.”

Still, the man said nothing, but he was staring at her with intense interest. Drew was made a little dizzy by the attention.

She kept talking. “The duke in question was the cause of some scandal several years ago. His reputation was so damaged, he was forced to leave London.”

And now, Drew could actually hear herself saying too much, but she couldn’t seem to stop.

“It was a pity, really,” she went on, saying it all, saying things she didn’t even know to be true. “He’d shown great potential in the House of Lords. But he was responsible for an early Luddite riot. He incited the march and then betrayed his own tenants to the authorities. It was widely reported in the broadsheets. It ruined him really, which will make the debut of his girls very challenging, indeed. They’ll need to tread very carefully. But never fear, I specialize in these scenarios. It is my favorite sort of project.”

She had just said it, the words barely out of her mouth, when the doors to the Throne Room were thrust open. A liveried footman appeared.

“His Grace, the Duke of Lachlan,” the footman intoned, half question, half proclamation. A summons.

“Aye,” answered the man beside Drew. “Lachlan.”

To Drew’s great horror, the man beside her—the Duke of Lachlan—stepped around the footman, strode through the door, and disappeared into the Throne Room.

He did not look back. The doors slammed shut.

Drew stared in horror at the thick gray wood while her words revolved in her head like a swarm of Dartford warblers.

. . . . . .

Chapter Two

“Mystery solved,” muttered Ian Clayblack, the Duke of Lachlan, coming to a stop before Prince Adolphus. He affected a stiff bow.

“What was that, Lachlan?” called Prince Adolphus, sitting on a throne that looked very much like an upholstered wingback chair. Beside him on a matching wingback-like throne was a young woman in streaming pink ribbons and bouncing yellow curls.

“Good morning, Your Highness,” Ian corrected in a clipped voice.

To the woman he said, “How do you do, Princess. Felicitations on your nuptials.” The words were pleasant but his tone was not.

“What mystery?” demanded the prince.

“The mystery of why you summoned me.” He looked around. “Here.”

“I summoned you because you amuse me, Lachlan.”

“Yes, but typically I amuse you over a pint of lager at the Ferryman Public House in Cumberland Road. I wasn’t aware that Kew Palace had a Throne Room. Nor that you held court.”

The prince made a dismissive gesture. “It’s no small thing to share the royal family with fifteen siblings, Lachlan. I must fight for my stake in this family. This is Mama’s embroidery room, if you must know. She allows my wife and me to use it the second Monday of every month to entertain causes that interest us.”

“So I’m a cause?” asked Ian, frowning.

Ian and Adolphus had served together in the army. They’d slept in a field and eaten gruel and roots and spit-fired salamanders. Ian considered Dolph an ally and a friend, but it was possible to cause real offense here; he was a bloody prince. He should force himself to tread lightly.

“Of course you’re not a cause,” the prince was assuring him. “And we shall drink together at the Ferryman soon enough. But now that I’m properly married…” he reached for his princess’s small hand, “…I am endeavoring to take my royal duties more seriously. We’ve a friendly history, it’s true, but let us not forget our larger roles. My father is Sovereign; you are a duke. You have goals in parliament, and I want to help you achieve them.”

“Right,” said Ian, not believing it for a second. This meeting was not about Ian’s goals, it was about—

“Pray tell me,” ventured the prince, “how are Evelyn and Ava?”

And there it was. Ian swore in his head. “Who?” he asked, knowing the answer—hating the answer.

“Your nieces, Lachlan.”

“Oh,” said Ian. “Imogene and Ivy.”

“Right, forgive me,” corrected the prince. “How are the dear girls?”

“My nieces are well,” bit out Ian, not entirely a lie.

“You’re cross,” said the prince.

“I’m confused, Highness. You’ve a waiting room filled with loyal subjects who are about five minutes from coming to blows. Someone has broken a window. I would not wish to waylay your allotted Monday with your many adoring supplicants.”

“Ever a selfless man of the people,” mused the prince sarcastically.

“Indeed,” said Ian, still trying to gauge his motives. When the prince said nothing, Ian took a deep breath and dove right in.

“Fine,” Ian said. “Since you’ve asked, I’ve urgent need of a recall to the export duties in Bournemouth. The livelihood of my tenants—of so many craftsman in Dorset—will cease if they cannot ship their goods beyond England without being taxed to the teeth.”

“Oh yes, yes, tenants and taxes,” mused the prince. “I will see what might be done. But let us return, for the moment, to the diverting topic of your nieces.” He gave his wife a wink.

Ian suppressed a growl. He reminded himself that he’d expected this. His old friend had summoned him, but Adolphus had almost no power. The export levy was an issue for parliament or the king.

As to Ian’s nieces…Ian marveled that Adolphus had remembered the girls. If Ian had ever mentioned them, he had no idea why. Furthermore—

“Pray keep your dagger glares and ground teeth in check, Lachlan,” snapped the prince. “We’re not in a barracks and you’re distressing my wife. She is endeavoring to do the lot of you a very great favor.”

“Pardon, ma’am,” Ian bit out, bowing stiffly. “What favor?”

“Your two nieces have accompanied you to London, have they not?” asked the prince.

“They have,” Ian said, but in his head, he thought, No, no, no, you must be joking—No.

But of course the die had been cast.

The flame-haired woman in the antechamber had made this abundantly clear. What a terrible, seemingly unavoidable surprise. And Ian hated surprises.

“And you intend to host them in a Season and launch them into society?” said the prince.

“Something of the sort. If I can manage it.”

“You’re a duke of some means, Lachlan. Of course you can manage it. If you’re worried about that scandal with the rioters, surely that’s nearly forgotten.”

Or, thought Ian, it’s been remembered vividly—as evidenced by the woman who recited a distorted version of it to me just five minutes ago.

He said, “Yes, Highness.”

“Tell me what challenges you face with the girls?”

Nothing that has anything to do with you, thought Ian, but it was clear by the look on the prince’s face that he would have an answer.

“Ah, my sister—their mother—is a bit…distractable,” ventured Ian. “And the girls are very…raw.”

“Quite,” soothed the prince, his voice sympathetic. “This is what we’d heard.”

“Heard from whom?” Ian ground out. Beyond sending staff ahead to open the London townhouse, he’d told no one he was returning to London. Even less had been said about the girls.

“Oh, we have our sources, don’t we, Minnow?” the prince was saying, grinning at his wife. The princess scooted as close to him as their separate chairs would allow. She leaned over to whisper something in his princely ear. She was a pretty little thing, if your taste ran to sugary and young and petite, which Adolphus’s always had. And good for him. It was difficult enough to be a duke. Ian was certain that seventh son to a king came with a great many more challenges. Dolph should have his doll-like wife, but he should have her without treading on Ian’s already complicated life.

“If you can conjure the appropriate amount of respect and courtesy for my wife,” said the prince, “she would like to extend an offer—to you, for your nieces. Regarding their advancement.”

Why couldn’t people, Ian wondered, leave well enough alone? His only wish for himself and his family was to live their lives without comment or interference except to eradicate the bloody export duties on the livelihood of his tenants.

“My wife is offering to sponsor the girls,” said the prince. “Next spring. In their presentation at court. To Mama.”

Ian blinked. Surely he’d misheard.

“Presentation to the Queen,” Dolph clarified. “Of England.”

Ian forgot to be rude or respectful or even angry. “She’s what?” He gaped at Princess Cynde.

“You’ve heard me,” sighed the prince, leaning back.

Ian looked from his old friend, fat and self-important; to his petite wife, yellow hair framing her sweet face like curtains around a brightly lit stage.

“Thank you?” Ian ventured.

“You’re welcome,” chirped the princess, her first words. She had a twee voice that matched her ribbons.

Ian ignored her and waded through this wholly improbable offer in his mind.

Truth: he’d brought Ivy and Imogene from Dorset to host them in a London Season.

Truth: he’d intended to see the thing done properly, in the manner befitting a duke and his family.

Truth: returning to London was the absolute last thing he’d wanted to do, and he wasn’t certain, even now, if it was best for the girls.

Untrue: he’d expected Imogene or Ivy to be presented at court to the Queen of England.

It was a gross understatement to describe the girls as “raw.” They’d returned to Avenelle three months ago, and he’d yet to determine exactly what his sister had done to cultivate their strange combination of sheltered and wild. What was worse, he had no idea how to correct it. He’d brought them to London at significant personal toll; honestly, he’d been at his wit’s end. Wasn’t this what young women did when they turned sixteen? They embarked upon a proper London Season?

Ian’s vision for their Season had involved their making the acquaintance of other girls, fittings for new wardrobes, a handful of carefully chosen parties, and a modest debut ball. And nothing more.

The Lachlan title amounted to an inconsequential dukedom in Dorset. His own scandal had put a stain on the family name. The girls would not run into lofty circles or pursue life at court. If they were very lucky, they’d pick up one or two refinements in London and return to Dorset by summer.

The thought of Imogene or Ivy, God bless them, surviving a royal presentation without incident seemed impossible—as likely as him returning to parliament without inviting public scorn. At best, wildly aspirational; at worst, a disaster.

“I knew you would be ungrateful and difficult,” sighed the prince, selecting a sticky date from a bowl.

“Forgive me, Highness, I’m—”

“And that is why I intend to sweeten the deal,” continued the prince.

“The deal?”

“As part of the girls’ introduction to Mama, I will further facilitate a meeting between you and my brother George.”

“The prince regent?” Ian rasped. Surely he’d misheard.

“Of course the prince regent. That is your larger goal, is it not? To persuade George to release the export duties on your tenants’ lace? My brother, in turn, will pressure the Lords. George owes me a favor, and now you owe me one.”

“Highness,” said Ian, the only word he could manage.

If the regent could be convinced to support the eradication of export duties on textiles and lace, Ian wouldn’t have to return to the House of Lords. He wouldn’t have to navigate the gossip or endure public scorn and relive the riots in every paper in London. He could slink back to Dorset and never be heard from again.

But at what personal cost? Imogene and Ivy presented at court? God help them all.

Ian cleared his throat. “If I might venture an amendment. With regard to my nieces…”

“You may not,” cut in Dolph. “The offer remains exactly as I’ve said. Your nieces are important to my wife and therefore, they are important to me. I cannot guarantee an audience with my brother if we don’t combine it with your family’s introduction to the queen. I’m a prince, but I’m not a bloody miracle worker.”

“No,” conceded Ian. “I don’t suppose you are.” If nothing else, Dolph was honest.

“But why is Princess Cynde so very invested in my nieces?” Ian was honest, too, and this arrangement made no sense.

“Don’t trouble yourself with the details,” Dolph drawled. “Take the bargain, Lachlan. Trust me that you won’t regret it.”

Ian stared at him, trying to comprehend the choice he was being forced to make.

His relationship with the Avenelle tenants hinged on the eradication of this export duty and the prince regent could be instrumental in making that happen. Regardless, one did not turn down an audience with the future king. It simply wasn’t done.

Perhaps he could also use the audience to explain himself. Salvage some part of his reputation at the highest level—God only knew what the prince regent thought of him or the riots.

He’d called on the prince with the dim hope of making some progress on the export duties. An audience with his brother, the prince regent, was so far and away better than his wildest dreams. If his nieces were also somehow tied to the deal—so be it. In Ian’s experience, very few things in life came easily.

“The next appropriate response, Lachlan,” lectured the prince, “is to ask the princess how you might repay this great generosity. What you and the girls must do to make her so very proud—both throughout their Season and on the day they meet the queen.”

“Right,” rasped Lachlan, snapping to. Of course he already knew. His nieces were only one half of the arrangement. There was also the young woman in the antechamber, her cheeks likely as red as her hair.

“Ian, for God’s sake!” shouted the prince, clearly annoyed.

“Ah, sorry, Dolph—ah, Your Highness.”

Ian looked at the princess. “But what can I do to best facilitate this great generosity, Highness?”

“Well, actually…” began the princess in her high-pitched voice. She raised her tiny hand and snapped at the footman standing sentry by the double doors. “I should like to introduce you to my dear sister…”

~ End of Excerpt ~

Order your copy of A Duchess by Midnight

Digital:

Audio:

→ As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. I also may use affiliate links elsewhere in my site.