USA Today Bestselling Romance Author

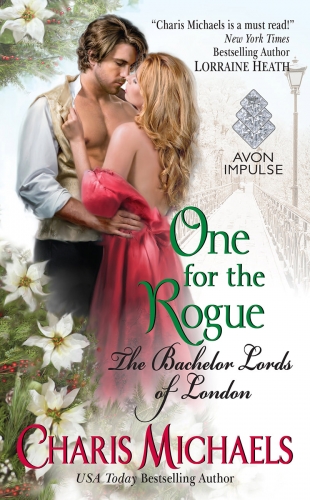

One for the Rogue

Book 3 of the Bachelor Lords of London Series

Beauregard “Beau” Courtland has no use for the whims of society and even less for aristocratic titles. As a younger son, he travels the world in search of adventure with no plans to settle down. Even when the title of Viscount Rainsleigh is suddenly forced upon him, he will not bend to duty or decorum. Not until an alluring young woman appears on the deck of his houseboat, determined to teach him propriety in all things and tempting him with every forbidden touch…

Lady Emmaline Crumbley has had a wretched year. Her elderly husband dropped dead without naming her in his will, and she’s been relegated to the life of dowager duchess at the age of 23. She has no wish to instruct a renegade viscount in respectability, but she is desperate to escape her greedy stepson, and Beau’s family makes her an offer she cannot refuse: teach the new lord to behave like a gentleman, and they’ll help her earn the new, self-sufficient life of her dreams. Emmaline agrees, only to discover that instructing the viscount is one thing, but resisting him is quite another. How can she teach manners to the rakish nobleman if he is determined to show her the thrill of scandal instead?

Connected Books

One for the Rogue

Book 3 of the Bachelor Lords of London Series

The full series reading order is as follows:

- Book 1: The Earl Next Door

- Book 2: The Virgin and the Viscount

- Book 3: One for the Rogue

Book Extras

One for the Rogue

Enjoy an Excerpt

One for the Rogue

Buy your copy →

Read or write reviews on Goodreads →

Prologue

This is the tale of two brothers.

No, allow me to go back. This is the tale of two half brothers, a distinction that does not affect the brothers as much as it creates a place for the story to begin.

They were born deep in Wiltshire’s Deverill Valley, less than a mile from the River Wylye, in a crumbling manor house called Rossmore Court.

Although the Rainsleigh title was ancient and the family lands entailed, the boys’ parents, Lord Franklin “Frankie” Courtland, the Viscount Rainsleigh, and his lady wife, Este, were not held in high esteem—not by their neighbors in Wiltshire nor by members of London’s haute ton. Instead, they were known mostly for their predilections: recklessness, coarseness, drunkenness, irresponsibility, and deep debt.

Their notoriety did not curtail their fun, however, and they carried on exactly as they pleased. In 1779, the viscountess became pregnant, and Lord and Lady Rainsleigh added “woefully unfit parents” to their list of indiscretions. Their firstborn was called Bryson—the future viscount, Lord Rainsleigh’s heir. Young Bryson was somber and curious, stormy and willful, but also inexplicably just and kind.

In 1785, Este and Frankie welcomed a second son, favored almost immediately by his mother for his sweet nature and easy manner, his angelic face and smiling blue eyes. The viscountess named him Beauregard, known as “Beau.”

On the whole, the boys’ childhood was not a happy one. Lord Rainsleigh was rarely at home, and when he was, he was rarely sober. He managed the boys with equal parts mockery and scorn. Lady Rainsleigh, in turn, was chronically unhappy, petulant, and needy, and she suffered an insatiable appetite for strapping young men, with a particular preference for broad-shouldered members of staff.

Money was scarce in those years, and schooling was catch-as-catch-can. The brothers relied on each other to get along.

Bryson’s hard work and good sense earned them money for new coats and boots each year, for books, and for an old horse that they shared.

Beau employed his good looks and charm to earn them credit in the village shops, to convince foremen to hire them young, and to persuade servants and tenants to stay on when there was no money for salaries or repairs.

And so it went, each of the boys contributing whatever he could to get by, until the summer of 1807, when the old viscount’s recklessness caught up with him, and he tripped on a root in a riverbed and died.

With Frankie’s death, Bryson, the new viscount, set out to right all the wrongs of his father and cancel the family’s debts. He moved to London, where he worked hard, built and sold a boat, and then another, and then another—and then five. And then fifteen. Eventually, he owned a shipyard and became wealthier than his wildest dreams.

Beau, on the other hand . . .

Well, Beau had no interest in righting wrongs or realizing moneyed dreams—he wasn’t the Rainsleigh heir, thank God. His only wish was to take his handsome face and winning charm and discover the delights of London and the world beyond.

For a time, he sailed the world as an officer of the Royal Navy. For another time, he imported exotic birds and fish. He spent more than a year with the East India Company, training native soldiers to protect British trade. His life was adventurous and rambling, sunny if he could manage it, and (perhaps most important) entirely on his own terms.

Until, that is, the day the Courtland brothers received, quite unexpectedly, a bit of shocking news that changed both of their lives.

The news, which they learned from a stranger, was this: the boys did not share the same father.

The horrible old viscount—the man who had beaten them and mocked them, who had driven them into debt and allowed their boyhood home to fall into ruin—was not, in fact, Bryson’s father after all. Bryson’s father was another man—a blacksmith’s son from the local village with whom their mother had had a heated affair.

Beau, as it turned out, was the only natural-born son of Franklin Courtland.

Beau was the heir.

And just like that, Beauregard Courtland became the Viscount Rainsleigh, the conservator and executor of all for which his brother had toiled over a great many years to restore and attain.

It made no difference that Beau had no desire to be viscount, that he was repelled by the notion, that the idea of becoming viscount made him a little ill.

In protest, Beau threatened to leave the country; he threatened to change his name; he threatened to commit a crime and endure prison to avoid the bloody title—all to no avail.

He was the rightful Viscount Rainsleigh, whether he liked it or not.

His brother, now simply Mr. Bryson Courtland, shipbuilder and merchant, set out on a new quest: to train, coach, and cajole Beau into becoming the responsible, noble, respected viscount that he himself would never be again.

To answer that, Beau seized his own quest: resist. He could not prevent his brother from dropping the bloody title in his lap, but he could refuse to dance to the tune the title played.

He would carry on, he vowed, exactly as he had always done—until . . . well . . .

“Until” is where this tale begins.

But perhaps this is not a tale of two brothers or even the tale of two half brothers.

Perhaps it is the story of one brother and how the past he could not change built a future that he, at long last, was willing to claim.

Chapter 1

December 1813

Paddington Lock, London

Emmaline Crumbley, the Dowager Duchess of Ticking, had agreed to a great many things in life that she later lived to regret.

She regretted leaving Liverpool to move to London.

She regretting marrying a decrepit duke, three times her age.

She regretted cutting her hair.

Most recently—that is, most immediately—she regretted striding down the wet shoreline of Paddington Lock at seven o’clock in the morning for the purpose of—

Well, she couldn’t precisely say what she had agreed to do.

Instruct a full-grown man on the finer points of eating with a fork and knife? On sitting upright? Teach him to smile and say, “How do you do?”

Teach him to dance?

“Good God,” she whispered, “I hope not.”

Her tacit agreement with Mr. Bryson Courtland, the new viscount’s brother, had not been a specific checklist so much as a vague wish to refine the new lord. A wistfulness. Mr. Courtland was wistful (really, there was no other word) about how perfectly suited Emmaline was to sort out his wayward brother. About how she might, in fact, be his only hope.

And there it was. The reason Emmaline had agreed to do it, despite her mounting regret. There was perhaps no stronger leverage than being anyone’s only hope.

And what Emmaline needed right now—more than she needed to stop agreeing to things or even to stop regretting them—was leverage. Leverage with the wealthy, shipbuilding Bryson Courtland, no less. If Mr. Courtland wished to see his brother trained in the finer arts of being a gentleman, well, she stood ready to serve.

The shifting gravel crunched loudly beneath her boots, and she walked faster, trying to outpace the sound. She spared another look over her shoulder. The canal was deserted at this hour, something she could not have guessed. Her plan had been to come early but not to find herself alone. In this, she was lucky for the fog. Visibility was no more than five feet. Just enough to make out the name on the last narrow boat in the row.

Trixie’s Trove.

A ridiculous name, painted on the hull in ridiculously overwrought script. Everything about the boat was, in fact, ridiculous, from the peeling purple paint to the viscount who lived aboard it.

Certainly the fact that she was broaching its wobbly stern for the third time this month was ridiculous.

Ah, but you agreed to this, she reminded herself. It is a very small means to a much larger end.

Squaring her shoulders, Emmaline contemplated the swaying gangplank, a rickety ribbon of loosely wired boards. She’d learned to navigate the moldering plank on her two previous calls to the houseboat and could easily step aboard without snagging the silk of her skirts (even while felt a small thrill each time the stiff black bombazine caught and tore).

Three more days, she reminded herself, and she could trade full mourning for half. In place of black, she would be permitted to wear . . . gray. Hardly an improvement, but at least she could get rid of the detestable, vision-blocking veil. And the black. Oh, how she detested the black.

Gulls squawked forebodingly in the distance, and she paused to scan the shoreline. The Duke of Ticking’s grooms had never trailed her this early in the morning, but their spying became more prevalent with each passing day. A quiet path was no guarantee of a safe one. At the moment, she saw only the misty shore, an empty bench, and the outline of the buildings lining New Road. Safe and clear. For the moment.

Drawing a resigned breath, she clasped the ropes on either side of the gangplank and teetered onboard.

The viscount’s houseboat was strewn with an indistinguishable jumble of provisions and rigging and dead chub. She knew to expect this from previous visits and now picked her way to the door. At one time, it had perhaps been painted red. Orange, maybe. Now it was a dusty, mud-smeared gray. Precisely the color, she hypothesized, of the viscount’s pickled liver. Thankful for her gloves, Emmaline took up her skirts to descend the steps that led to the door when—

Crash!

The door swung open and banged against the cabin wall. Emmaline skittered back, silently flailing, until she collided with an overturned barrel. She sat, swallowing a gasp and whipping around to gauge her distance to the side of the boat. Less than a foot, but she was steady, thank God, on the splintered planks of the barrel. She closed her eyes. Means to an end. A great favor for a great favor.

Female laughter burst from the door, and she opened her eyes. Three women staggered onto the deck in a chain of wild hair and sagging silk and dragging petticoats. At their feet, a dog pranced and barked.

“Give my regard to Fannie,” a man’s voice called after them.

“Oh, we’ll tell ’er, lovey!” called one of the women. More laughter. The trio linked arms and tripped their way to the gangplank, working together to stay upright. The dog, meanwhile, had caught scent of Emmaline and padded over to sniff the hem of her dress. She watched the dog warily and gestured in a shooing motion to the bustle of women trailing onto the shore. The dog ignored them and plopped her shaggy front paws on Emmaline’s skirts.

“Next time, I’ll be expecting Fannie,” the man’s voice called cheerfully again from within.

The viscount, Emmaline guessed. On previous visits, she had not heard him speak. Well, perhaps she had heard him speak but not actual words. He had mumbled something unintelligible. He had snorted. There may have been the occasional gurgling sound. She had come early today in hopes of discovering him in full possession of his faculties, especially speech. In this, she seemed to have succeeded, but she would never have guessed he would not be alone.

Now she heard footsteps. Something fell over with a clatter. There was a muttered curse, more footsteps. Emmaline shoved off the barrel and stood, her eyes wide on the door. The dog dropped from her skirts but remained beside her, and she fought the impulse to sweep her up into her arms. Protection. Ransom. Courage with a wet nose and shaggy tail.

But the dog left her when the man who matched the voice emerged to fill the doorway. Tall, rumpled, untucked, he leaned against the outside wall of the cabin and stared into the mist.

Oh.

She forgot the dog and took a step closer.

Oh.

But he was far younger than she’d thought. Not a boy, of course, but not so much older than her own twenty-three years. Twenty-seven perhaps? Twenty-eight?

And he was so . . . fit. Well, fitter than she’d guessed he would be. Of course she’d never seen him standing upright. The doorway was small, and he was forced to angle his broad shoulders and stoop to see out. He hooked his large hands casually on the ledge above the door and rested his forehead on a thick bicep. Squinting lazily, he watched the women disappear into the fog.

One of them called back, an unintelligible jumble of hooting laughter and retort, and he huffed, a laugh that didn’t fully form.

Emmaline looked too, ever worried about the grooms, but the shoreline was a swirl of cottony mist.

When she swung her gaze back to viscount, he was no longer laughing or squinting. Now, he stared—but not at the shoreline.

The viscount was staring at her.

. . . . . .

Bloody, bleeding hell, the blackbird was back.

At the damnable crack of bloody dawn.

Beau Courtland thumbed through his mental guide to making oneself disappear. It was too late to hide or feign unconsciousness, but he could always plunge over the side and into the canal. Limited options, really, but he was highly motivated.

“Lord Rainsleigh?” the woman called, taking a step toward him.

Beau stared.

“Lord Rainsleigh?” she called again, louder this time. As if once hadn’t been terrible enough.

His eyes flicked to the side of the boat. The canal would be icy in December, but he was growing less and less particular.

“You have the wrong boat,” he called back, beckoning his dog with a snap of his finger. Peach trotted to his side.

“I am the Dowager Duchess of Ticking,” she went on, “How do you do?”

Buggered, he thought, and you?

And now they both had titles? Brilliant. This ruled out charity crusader, which had been his first guess. Or missionary, which had been his second. She wore enough black fabric to smother a horse and a stiff black veil, which obscured half her face. He couldn’t see her eyes.

“I’ve come at the request of your brother,” she continued.

Beau swore. The only thing more tedious than his title was his brother’s ambitions for it. His mood spiraled, and he dropped his hands from the door jamb and trudged up the steps to the deck. Useless move, because he still couldn’t see her face. Although . . . nice mouth, for all that. Pink and plump and pursed into a pout.

He knew from the lilt in her voice that she was young. And her posture. Upright and effortless. Her mouth was . . .

It occurred to him that he’d gotten close enough. In fact, he fought the urge to take a sudden step back.

“I’m here about the tutorials,” the veiled woman said.

“What tutorials?”

“Well, guidance—for you, really. As you assume your new role as viscount.” She closed the last steps between them and folded the veil back with black-gloved fingers. She turned up her face.

Now he did take a step back.

The face that blinked up at him seemed to burn away the morning fog. Large brown eyes, thick lashes, a dimple on one creamy cheek.

And that mouth.

“Comportment,” the mouth was saying, “manners, responsibilities, life at court. I am an acquaintance of your brother, Mr. Bryson Courtland. He has, er, asked me to help you settle in to the expectations of your new role as viscount.”

And just like that, their conversation was over. “Good-bye,” he said.

Later, he would look back and concede that his brother had played it very well. A shockingly pretty girl—a widow, no less, his favorite. Delicate. Large eyes like a baby owl. The dimple. The mouth.

Later, he would curse his decision not to leap over the side and swim for Blackwall.

Instead, he dismissed her. Firmly, with finality and conviction. At his feet, Peach barked once for dramatic effect.

And then he turned on his heel and strode across the deck, clipped down the steps to the door of cabin, and was gone.

Chapter 2

Emmaline stared at the wet spot on the deck where the viscount had been.

A crash sounded from inside the cabin, and she looked to the open door. She picked her way across the deck to the top step. “If you please, Lord Rainsleigh?” She peered into the dim interior. “We haven’t yet—”

“If the arrangement was with my brother,” he called from inside, “then I suggest you tutor him in manners and comportment and life at bloody court.”

“On the contrary,” Emmaline called down the steps, “your brother feels quite strongly that these are areas in which you—”

“How much is he paying you?” He popped his head out of the door.

Emmaline straightened. The sun was up now, and she could see his face more clearly. His eyes were blue. Terribly, piercingly blue, like the underpinning of a flame. “I beg your pardon?”

“My brother. How much has he paid you to hunt me down and train me to roll over and play dead?”

“Play dead?” she repeated.

“Whatever the sum, I’ll double it.”

“Sum?” She sounded like a parrot, repeating everything he said, but she hadn’t been prepared to tell him the terms of the arrangement with his brother. She hadn’t been prepared to tell him anything about herself at all.

Mr. Courtland had suggested that his brother would be “reluctant,” but she would pin this more like “opposed.” Aggressively opposed.

“I’ve never paid a woman to go away,” he said, looking her up and down, “but there’s a first time for everything.”

Emmaline felt herself blush. She also had not been prepared for him to provoke her. “Oh, but your brother has not paid me, my lord.” This was not precisely a lie. “I am a duchess.”

“Congratulations.” He disappeared inside again, and Emmaline was left staring down at his dog. She heard rustling, the sound of something heavy being slid, pots clanging together.

“I’ve agreed to help,” she called, “because your brother and sister-in-law have done me a great favor, and I am indebted to their kindness.” Another not-quite lie. In fact it was very true, indeed. There was more, far more, but surely this was enough to end the discussion of payment in as many words. Even before she was a duchess, Emmaline had never worked in her life.

“No money was exchanged, certainly,” she said, just to be perfectly clear. “And my assistance is meant to be quick and discreet. Only the fundamentals—an overview, really. Four sessions. Perhaps five. I’m certain if you would but hear what I propose—”

“Don’t care,” he called back. His dog padded inside and turned around to stare up at her through the door.

“I am a dowager duchess,” she went on, “in case you’re worried about . . . about . . .” She allowed the sentence to trail off, unable to name anything that might worry him. Of course he wouldn’t care that she was a duchess, widowed or not. She wasn’t prideful about the title, but her strategy had been to catch him off guard and use it to bully him. It wasn’t every day a dowager duchess showed up to one’s floating rubbish bin and offered to . . . to . . . bestow her wisdom, such as it was.

Emmaline closed her eyes. She’d assumed the viscount was too thick or awkward to grasp the manners of a gentleman, that it would be easy to gently guide his simpleton’s brain through basic etiquette. But that wasn’t the case at all. This person wasn’t stupid; this person simply did not care.

“You’ve no care at all,” she confirmed, “about your comportment?”

“None.”

“But . . . why?”

“What difference is it to you?” He poked his head out again. He was wearing a hat—a weathered, tanned-leather hat pulled rakishly low over his vividly blue eyes. “If he’s not paying you?”

“Well”—she hesitated only half a second—“he and his wife saved my brother’s life.”

“Hmm. They’re useful in that way.” He disappeared again. She heard the rattle of a chain or keys on a ring and the thunk of a trunk lid.

“Would you not, at the very least, tell me why you refuse the lessons?”

“No,” he called. “I won’t. Why not repay my brother himself? You couldn’t know this, but he adores balls, garden parties, seats at the opera. The more dukes and duchesses he knows, the better, in his view.”

Emmaline shook her head and hurried down another step. “Oh, but my husband is deceased, Lord Rainsleigh. As a dowager duchess, I am less privy to operas and balls and such. And anyway, your broth—”

“Dowager?” he said, appearing again, “as in, grandmother?” Now he wore a sweeping leather overcoat that whirled around his boots like a cape. His hands opened and closed as he fitted them with tight leather gloves. He fastened what appeared to be dagger into a sheath on his belt.

Emmaline blinked. He looked nothing like a viscount, but not for the reasons she had guessed. When she’d called before, she’d considered his slouched, unconscious form to be droopy or atrophied, lazy or faint. That was . . . inaccurate. He looked like a highwayman, nimble and wild and dangerous.

She stumbled back half a step.

“No, not a grandmother,” she said. “My husband has died, and his son from a previous marriage has inherited. The new duke’s wife is the duchess. I am the dowager duchess.”

The viscount frowned. “How old are you?”

“Of course a gentleman would never demand to know the age of a lady.”

For a moment, he seemed to consider this, but then he reached out and grabbed her arm. “Sorry to ruin your morning, sweetheart, but this conversation has run its course. And I’m expected in Newgate.” He gave her arm a tug, mounted the steps, and hustled her up to the deck.

. . . . . .

The dowager duchess gasped and stared at his hand on her arm. Beau ignored her and kept coming, handing her up, dragging her up. Peach leapt and barked at their feet.

“Here is the rub, Lady Tickle,” he said.

“I am the Dowager Duchess of Ticking,” she insisted, trying to yank her arm free.

“Bloody hell, you’re a skinny little thing.” He said this to keep himself from not saying the half dozen other observances prompted by her sudden proximity. Her reflexes were quick and athletic; her breast against his wrist was small and pert—his preference. The smell of her was clean and bright and like nothing he’d encountered since he’d installed himself on the canal. The hair she tucked so severely beneath her awful hat was blonde—bright gold-streaked blonde, the color of sunshine on the sand.

“This is just the sort of unwelcome comment that I would advise against in my tutorial,” she gasped.

“ ‘Unwelcome,’ is it?” They reached the top step, and he began to weave her around the coils of rope and piles of rigging to the gangplank. “Allow me to illustrate the meaning of the word ‘unwelcome.’ My brother abdicated the title to me against my will. It was unwelcome.” He paused, kicking a buoy out of the way. “I deplore the bloody thing. You may tell my brother, not for the first time, that I will not wear a viscount’s costume, or live in a viscount’s house, or fill my days with viscount-like pursuits, whatever they are.”

“But . . . why?” she asked, scrambling to keep up.

Because I can find plenty of less important ways to fail, all on my own, he thought, and have a better time doing it.

“Because the very idea bores me to death,” he said. This was also true, of course. There were other reasons, but she would not be privy to them. Even his brother did not know these.

Why Bryson had insisted upon giving up the bloody title, when only five living souls knew his parentage was illegitimate, was a mystery he would never unravel. No one else needed to know he didn’t happen to be blood related to the viscount’s long line of aristocratic rotters.

Except Bryson claimed that he himself would know, and he had too much respect for the ancient-lineage rubbish to deceptively carry on when he had no real claim.

Bollocks.

There was such a thing as being honest to a bloody fault.

And to no good end.

And at the cost of someone else’s entire bloody life.

Not that the duchess needed to understand any of this. The duchess needn’t understand anything more than “sod off.”

They came to the little metal gate that blocked the gangplank, and he kicked it open with his boot. “Get out,” he said.

“Lord Rainsleigh,” she implored, tugging at her arm.

“Stop calling me that.”

She opened her mouth to object when the sound of footsteps rose from the pathway beside the water. She whipped her head around.

At their feet, Peach grew very, very still and sniffed the air, letting out a low, ominous growl.

The duchess cocked her head to the side, listening.

The footsteps continued. Closer now—louder. Peach barked once, twice.

Under his hold, her entire body went taut. He studied her face. She was holding her breath.

“What’s the matter?” he heard himself ask. He released her arm.

She held up a hand to quiet him, staring wildly at the shore.

The steps on the path trod closer. More than one person. Two sets of boots, maybe three. A stray cough. Peach leapt from the boat and ran down the shore in the direction of the sound, barking into the fog.

The duchess took two steps back. She looked right and left, paused to listen, and then looked again.

“What’s the matter?” he asked again. She’d taken on the look of someone who might, at any moment, whip over the side and swim away. She didn’t answer, didn’t even look at him. She raised her hands to her horrible hat and tugged the veil back over her eyes.

“This isn’t finished,” she said, gathering up her skirts.

Beau was ready with a retort, to inform her that it was, in fact, finished, but she scrambled around him to the gangplank. He sidestepped to let her pass, and she darted from the boat. In seconds, she was swallowed by the fog. She didn’t look back.

Beau watched the hazy spot where she had gone until the approaching footsteps grew loud enough to be shapes in the fog and then men. There were three of them. Liveried grooms. They shuffled along the path beside the water, looking around, mumbling among themselves. Peach trotted behind them importantly, as if she had herded them his way.

They glanced at him and then on down the canal, clearly unimpressed. He had that effect on people. And it was exactly the way he liked it.

Chapter 3

When Emmaline bustled to her carriage, the driver and two of the grooms were gone.

The lone remaining groom stammered an explanation—something about hearing the sound of a child’s scream. His colleagues, he claimed, had dashed away to render aid.

Emmaline murmured her concern and climbed into the carriage to wait.

And now there would be screaming children. How creative. She would add this to the list of previous excuses, including ladies robbed at knifepoint, fisticuffs, spooked horses, and overturned carts. Every manner of crisis seemed to follow her carriage and require the pressing attention of at least two of her grooms.

Bollycock.

The servants were away because they had been following her. The Duke of Ticking made certain of that. If she managed to give them the slip (as on this foggy morning), she returned to an unattended vehicle. More often than not, she beat them back.

She’d already endured eighteen months of mourning, long enough by far to venture outside the house. She was careful to only make church or charity calls (as far as anyone knew). And yet Ticking had her followed everywhere. What a pity his spies were not clever enough to determine how she evaded them. In the front door of any given church and out the back—that was how she did it. From the rear alley, she could go wherever she pleased. In Paddington Lock and beyond, if she was careful.

Oh, but she’d cut it very close today. She could not fathom the punishment for being discovered on a canal narrow boat with . . . well, with a viscount who looked more like a brigand than a gentleman. Ticking already tightened his restrictions on nearly a weekly basis. More spies more of the time. It had become increasingly difficult to weave together the many elaborate strings of her plan. She could not endure more surveillance. She must redouble her stealth. Accomplish more in less time with each precious trip outside the house. Most of all, she must pin down the viscount and make him agree.

When the absent grooms finally returned, they offered precious few details about the alleged child and his alleged screams, and Emmaline smiled serenely and pretended to read her Bible for the journey home. Better to bore them to death, she’d learned, than take care with what she said.

“Master Teddy is in the Green Room, Your Grace,” her butler, Dyson, informed her when she arrived at her tidy dower house in the rear garden of the new duke’s townhome mansion. “Only one visit this morning from His Grace,” he added.

“Thank you, Dyson,” she said, smiling a sad, knowing smile. The butler had relocated with her from Liverpool when she’d married the old duke. He’d suffered a demotion and wage cut to remain in her service, but he was loyal and grandfatherly, and Emmaline wasn’t quite sure how she would have survived the move—or the Duke of Ticking—without him. She’d made him butler as soon as the duke was dead.

The Green Room was so named for the color of the ceiling, but the towering floor-to-ceiling alcove window that looked out over the lush dower-house garden offered a view equally verdant. It was one of her brother’s favorite rooms, and she was gratified by every small thing that brought him joy. When their parents had set sail on their ill-fated Atlantic crossing, Teddy had come to live with her and the duke in the ducal townhome. He’d not wanted to be left behind, but then to learn of the shipwreck? He had been steeped in sadness, mourning in his own way, unsettled and afraid. The cold marble, dark wood, and stained glass of the four-hundred-year-old townhouse had not aided matters. There were days when it had been difficult to coax him from his room. But the dower house was small and snug, just two levels and a cellar, six bedrooms, a dining room, a parlor, and the Green Room. It was smaller than their childhood home by leagues, but it had a door that closed and a garden with a wall. Until Emmaline could enact her plan and escape the duke altogether, it was vastly preferred. It was home.

Now she paused at the door to the Green Room, listening for her brother. The voices inside were low and reasonable, not unpleasant. God help her, they almost sounded . . . happy.

“Have I missed breakfast?” she said brightly, walking in.

On a settee by the window, her brother, Teddy, hunched over a large colorful book spread across his lap. Miss Jocelyn Breedlowe, his new caretaker, sat beside him, pointing at what appeared to be an illustration of a tree filled with tropical birds.

Teddy looked up. “Malie,” he said, referring to her by the name he’d called her since boyhood. He’d been late to speak and later still to call anyone by name.

Her heart clenched when she saw him now—his handsome face sharpening into manhood more every day. On the outside, he looked every bit the young, handsome heir to their father’s great fortune. Nineteen years old. Tall, broad-shouldered, always smartly dressed by Mr. Broom, the valet he’d had all of his life.

Only his brain had been left behind—stunted, somehow, since birth. In his mind, he was forever aged four or five. He could memorize the Latin names of an aviary of birds in one afternoon but still struggled to make simple conversation or find his way to the park and back.

“And what do we have here?” Emmaline asked.

Miss Breedlowe looked up and smiled gently. “Parrots,” she said. “Teddy has memorized the scientific names of all of these lovely birds.”

“This I believe,” said Emmaline, coming to stop in front of the book. “Which is your favorite, Teddy?”

Without looking up, he pointed to the colorful illustration of a robust, spectral-hued bird. “Parrot,” he said. He rattled off a glossary of on-word facts about the habitat and feeding of a rainbow parrot. “Get one, Malie?”

“Take on a parrot? I’m not sure the animal you described would be comfortable in London, would he?”

Teddy appeared to think about this, staring at the illustration.

“But perhaps we can locate a few more books about him,” said Miss Breedlowe. “We might even try our hand at sketching him, you and I.”

Teddy did not answer, his attention still on the book, and Emmaline winked at Jocelyn.

“I had the maids build a second fire in the opposite grate,” Jocelyn said, stepping away. “He prefers this room above all others, but I worry about the chill that seeps through the glass.”

“Yes, please,” said Emmaline. “Do what you can to be comfortable. I’ve suggested to His Grace that the room would benefit from velvet curtains to stave off the cold, but I won’t hold my breath.”

They chatted a moment more about Teddy’s morning. Not since her parents perished on their voyage to America had Emmaline had a confidant with whom she could discuss her brother. In this way—in every way—meeting Jocelyn Breedlowe had been a godsend. Jocelyn was compassionate and measured with Teddy, not to mention helpful and inventive. Emmaline had wept with relief and gratitude after their first session.

Ironically, it was Emmaline’s own failure to her brother that brought Miss Breedlowe to them. Teddy had gone missing in October—two harrowing days and a sleepless night with no trace of him—until charity workers employed by a woman named Elisabeth Courtland had stumbled upon him and brought him in from the streets, thank God.

Along with the return of Teddy, Emmaline had gained two new friends—Elisabeth Courtland and one of her volunteers, Jocelyn Breedlowe. When Emmaline learned that Jocelyn was a professional caretaker, she hired her immediately to help Emmaline do better at looking after Teddy. Jocelyn was another set of hands and pair of eyes but also support and respite for Emmaline.

Most of all, Jocelyn allowed Emmaline to slip out of the house to pull together the intricate plan that would, she hoped, earn her and her brother’s freedom from the Duke of Ticking.

In the weeks that followed Teddy’s rescue, Jocelyn Breedlowe had become so much more than a caretaker; she’d become a new friend. Emmaline had no idea how badly she needed friends until she met Elisabeth and Jocelyn. Sometimes she felt Jocelyn was as essential to her own sanity as she was to Teddy’s care.

“Your errand went well, I hope,” Jocelyn said casually.

Went well? Emmaline repeated in her head, thinking of the viscount—of his obstinacy and his flippancy, of his immediate rejection for the harmless, mutually beneficial thing she had offered him.

Inexplicably, she also thought of his blue eyes, easily the least useful detail to remember.

She snapped her head up. “Quite well. There’s more work to be done still, but it was another step.”

The agreement she’d made with Bryson Courtland had been vague and casual at best, and Emmaline had not shared the specifics of it with anyone, not even Jocelyn. She’d told her only that she was making plans for her and Teddy’s financial independence, that it was terribly important business, and that Teddy’s inheritance was at stake. For now, that was enough. Until she’d managed to gain control of any one of the five or six spinning plates in her wild scheme, she would keep the specifics close.

Now, she told Jocelyn, “Dyson said the duke called while I was out.”

Her friend nodded into the dying fire. “He did, I’m afraid. Not thirty minutes after you’d gone.”

“Heavens, I left at dawn. His staff must watch us at all hours. What reason did he give?”

“Oh,” Jocelyn said with a sad chuckle, “the usual things. He wished to know when you were due to return, where’d you’d gone.”

“None too subtle, is he?” Emmaline let out a tired breath and raised her hands to her hair to fish for the nagging pins that held her hat in place. Before she was free of it, Dyson appeared in the doorway and cleared his throat.

“His Grace the Duke of Ticking to see you, Your Grace,” the butler said pointedly. Dyson was proficient at announcing the new duke and warning Emmaline in the same breath.

Emmaline made a face and worked more diligently on the hat. “Thank you, Dyson, I shall meet His Grace in the drawing room. Can you show him in—”

“Do not bother, Emma,” said the duke as he strode past the butler. He glanced around proprietarily, as if he had immediate designs on every corner of the room. He was a short, ruddy man, purposeful to the point of doggedness. His face was perpetually creased with a look of unspecified determination. I shall, it always seemed to say. He made the simple act of selecting a chair and taking a seat seem like a scheduled event. His schedule, of course, his event.

Emmaline snatched the hat from her head and smoothed her hair.

The Duke of Ticking went on. “I won’t linger. I just came to bid you good morning and make certain you returned safely home.”

“I am quite safe, Your Grace,” Emmaline said.

“One can never be too cautious—a young woman alone, especially so early . . .” The duke allowed the sentence to trail off. He raised his eyebrows at her, allowing his deep curiosity to show. “Where did you say you’d gone?”

“Oh, I’ll not bore you with my charity errands.”

“The church employs clergy, as I’m sure you’re aware, to carry out the Lord’s good work.”

She smiled vaguely and studied her hat. If he wished to explicitly restrict her movements, she would make him say it in as many words. She waited.

“I only mention this,” he went on, “because Marie, Bella, and Dora had a mind to call on the dressmaker’s later this morning, but I will need our family carriage. I thought to send them in yours, but I couldn’t say for certain when you would return.”

“Quite,” Emmaline said.

Marie, Bella, and Dora were three of the duke’s oldest children. Or three of his middle children. There were so many of them, she struggled to keep track. None of them rose before eleven o’clock in the morning—this she knew—and it was only now nine thirty.

“I should think you might enjoy a shopping trip with the girls,” Ticking mused, “considering your proximity in age. They quarrel with their mother, but you may have a calming influence on them, just as you did on their grandfather.”

The duke never failed to mention Emmaline’s age in relation to both his own young daughters and his dead father.

“Forgive me, Your Grace, but I was under the impression that the smaller, older carriage was mine to use exclusively, as dowager duchess,” Emmaline said. “When I assumed residency in the dower house, I was told the carriage came with it.”

“It is my preference that we share the vehicles in this family,” Ticking said, speaking to the ceiling as if conjuring up a high ideal.

“I see. If you’re in need of my carriage for your children, you need only tell me in advance. I can rearrange my schedule.”

He pivoted in a half circle. “Is it truly your carriage, Emma?”

Yes, it is, actually, she thought, anger and frustration simmering. The carriage is mine. The dower house is mine. Even your carriage and the grand townhouse in which you live are mine—salvaged from the auction block with the dowry my father paid to marry me to yours.

Instead, she said carefully, “I understand your concern about the carriages.” She’d overheard her father say this to business associates many times. I understand. When there was nothing more to be said, this statement neither agreed nor disagreed, but it got in a word.

And it wasn’t even a lie; she did understand all too well.

She understood that her husband had fallen from his horse and died before he’d bothered to include her in his will, binding her to the miserly new duke as dependent and tenant and hostage.

She understood that her parents’ ill-fated trip to America had taken their lives before they’d determined how to pass down their prosperous family business and tidy fortune to Teddy. As male heir, he was entitled to it, but his mental state meant he could not manage any of it.

Most of all, she understood that her own gender entitled her nothing—not her parents’ money and not even the dowager stipend, if the Duke of Ticking did not wish to dole it out.

She’d spent the last year and a half trying to challenge this understanding from every possible angle, freeing herself and Teddy from the legal trap and social prison that fate had so cruelly landed in their laps.

Across the room, the duke ran a hand over the smooth, pomaded surface of his hair. “Very good, then. Will you require use of the carriage tomorrow?”

She looked at him. This was none of his business, and he knew it. “I may send it to fetch Miss Breedlowe,” she said.

“Ah, yes. The new nurse. How are you getting along, Miss Breedlowe?” He squinted at Jocelyn.

“Very well, Your Grace,” Jocelyn said, “but I should not take credit for being a proper nurse. I am merely a companion to Teddy.”

“A companion, yes . . .” His voice always spiked when he spoke of Teddy—louder still when he spoke to the boy.

He ambled closer and bent at the waist, his face two feet from where Teddy sat with his book. “I say! Teddy? How do you like your new nurse?”

Teddy looked up at the duke and then to his sister, his eyes uncertain. Teddy was not accustomed to bellowing, and he’d never liked Ticking, but Emmaline had warned him repeatedly against rudeness to the duke. She held her breath and nodded slowly to him.

“That’s right, Teddy,” she urged. “Can you bid His Grace a good morning?”

Teddy’s gaze swung back to the duke.

“Are you sure he does not require a doctor’s care?” asked Ticking, studying him as he would an animal in a zoo.

“Quite sure,” Emmaline said in a clipped tone. Her simmering patience had rolled to an angry boil. “Say hello to His Grace, Teddy.”

Miss Breedlowe moved silently to the boy and slipped the book from his hands.

“Quite fond of that book of yours, Teddy?” said the duke.

“Parrots,” said Teddy.

“Parrots?” the duke repeated. “And what need might we have for parrots in England? Planning a journey to the tropics, are you?”

“Teddy is a student of the life sciences,” Emmaline said.

“I asked the boy,” snapped the duke.

“Parrots,” Teddy repeated. Emmaline felt his tenseness mounting like a string being pulled back from a bow. He couldn’t tolerate being hemmed in, especially by someone with a booming voice whose morbid expression was at odds with the interest he showed.

“Shall I take Teddy out to break the ice on the fountain, Your Grace?” asked Jocelyn, God bless her. She put a calming hand on the boy’s shoulder. “This is something he and I had planned to do for thirsty birds in want of a drink.”

“That sounds lovely, Miss Breedlowe. Thank you,” said Emmaline. “Off you go.”

Miss Breedlowe leaned to whisper something in Teddy’s ear and, miraculously, he nodded. Ticking watched their exit with a keen, calculating eye.

“If that will be all, Your Grace,” Emmaline said, “I hoped to join Teddy in the garden before Miss Breedlowe leaves.” She smoothed one of the feathers on her hat.

The duke lowered fleshy lids over pale eyes. “I would bid you not to fret, Emma, over the money you’ve spent to have your brother looked after. This expenditure does not trouble me.”

Not fret over the money? Emmaline had not used the modest allowance Ticking allotted her to pay for Miss Breedlowe’s service. Her parents left her money to care for Teddy when they set sail on their doomed journey. She paid Jocelyn from this account. But she dare not make specific remarks on any of Teddy’s finances to the duke. The less the duke knew about Teddy’s money—before their parents’ drowning and after—the better.

“I understand,” she said again.

“Now that you have such a capable caretaker for the boy,” he went on, “you may wish to spend more time in the company of my children. My father adored them, you know.”

Well, that was a lie. The late duke had been appalled that his son and daughter-in-law had willfully reproduced seventeen times (and counting), and he was never so annoyed as when his son brought any fraction of the wheedling grandchildren for what always proved to be a raucous and destructive visit.

But now Ticking would expect some general commitment. This was his way. He made disagreeable statements and waited, daring her to oppose him.

He watched her speculatively.

Emmaline cleared her throat. “My plan has been for Miss Breedlowe to allow me a few hours outside the house for charity pursuits. Otherwise, Teddy and I enjoy each other’s company. We always have.”

Ticking nodded with feeling. “You are a devoted sister,” he said, pity in his voice. In his mind, Teddy was a burden. Well, a burden or a bag of money.

“Thank you.”

“The duchess and I had hoped you would be a devoted grandmama too,” he went on. “Furthermore, the company of children is a perfect diversion for a lady in deep mourning. Far more acceptable, some might say, than charity work outside the house. Before sunrise.”

“Oh, but I’m only in full mourning for three more days, Your Grace. And I’m afraid I might find myself entirely out of my depth amid seventeen children.”

“Nonsense,” he said. “Your many years with Teddy will serve you well. Intelligent, capable children may prove a relief to you after looking after a boy who struggles so.”

Now, Emmaline could but stare.

“Think on it, Emma,” he instructed, turning on her to stride to the door. “Think about your background and what you bring to this family. Here is a way to contribute.”

And there it is, she thought. The real “burden” to the dukedom has always been me—the common merchant’s daughter whose dowry sustains them even while my breeding makes them look the other way.

~ End of Excerpt ~

Order your copy of One for the Rogue

→ As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. I also may use affiliate links elsewhere in my site.