USA Today Bestselling Romance Author

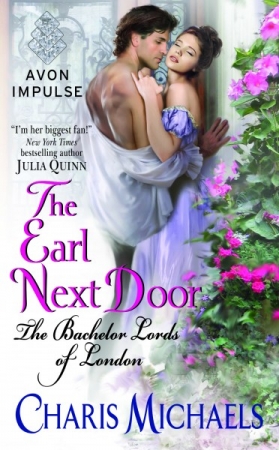

The Earl Next Door

Book 1 of the Bachelor Lords of London Series

American heiress Piety Grey is on the run. Suddenly in London and facing the renovation of a crumbling townhouse, she’s determined to make a new life for herself—anything is better than returning to New York City where a cruel mother and horrid betrothal await her. The last thing she needs is a dark, tempting earl inciting her at every turn…

Trevor Rheese, the Earl of Falcondale, isn’t interested in being a good neighbor. After fifteen years of familial obligation, he’s finally free. But when the disarmingly beautiful Piety bursts through his wall—and into his life—his newfound freedom is threatened…even as his curiosity is piqued.

Once Piety’s family arrives in London, Falcondale suddenly finds himself in the midst of a mock courtship to protect the seductive woman who’s turned his world upside down. It’s all for show—or at least it should be. But if Falcondale isn’t careful, he may find a very real happily ever after with the woman of his dreams…

Connected Books

The Earl Next Door

Book 1 of the Bachelor Lords of London Series

The full series reading order is as follows:

- Book 1: The Earl Next Door

- Book 2: The Virgin and the Viscount

- Book 3: One for the Rogue

Author's Notes

The Earl Next Door

Buy your copy →

Third Time’s the Charm

The Earl Next Door was the third manuscript I ever wrote, but my first published book. An early draft of the manuscript finalled in RWA’s Golden Heart contest in 2014. A perk of finalling is the opportunity to pitch to editors, and I sat down with Chelsey Emmellhainz from Avon to describe the story of an American heiress and her home-renovation project from hell. She asked to see the full manuscript and six weeks later, she offered me a contract.

And Then We Took an Unplanned Turn Towards Athens

The intrigue involving Joseph Straka in the final half of the book was added in revisions. My editor felt we needed an 11th-hour layer of conflict when Jocelyn’s love story was removed.

Trevor’s early life of crime in Greece was always a part of his character, so it was easy to flesh out the Greek mafioso who descends on London to menace Piety. Not so easy: figuring out how to get rid of Straka after he had been introduced. As my revision deadline loomed, “Adios’ing Straka” became a plotting quagmire from which I thought I might never get free. Finally, it was my mother who off-handedly said to me: “Why doesn’t he just go to jail?”

And the plan to trap Straka in his own game and send him to jail was born. Keep it simple, Sweets.

“I love this heroine, and I never say that!”

I have received this reader comment about Piety Grey more than once, and it is so gratifying. I, too, love Piety. I wish I had her courage and optimism and openness. Piety is the quintessential old-school heroine that feels like the loveliest version of aspirational me on my best day.

The character of Piety is loosely inspired by the character of Taylor Townsend in the TV show “The O.C.” I was a huge fan of the show and especially of the character of Taylor. Autumn Reeser, the actress who portrayed this character, was the image I used for Piety in my head as I wrote.

They’ve Still Got It

It was my great pleasure to revisit Piety and Trevor in my fifth book, All Dressed in White, in a lengthy scene that shows them happy and healthy and as mentors to the couple in that book. Writing the scene between an all-grown-up Joseph Chance and a middle-aged Falcondale was one of my favorites of all time.

Hyperbole, Thy Name is Limpett

Eli, Ennis, Everett, Emmett and Eddie Limpett, heirs to the New York City stocking empire. What can I say? If not in a romance novel, then where? If not to attack the heroine in a church and receive a beating from the hero, then for what other purpose? None, I tell you, none!

Book Extras

The Earl Next Door

Enjoy an Excerpt

The Earl Next Door

Buy your copy →

Read or write reviews on Goodreads →

. . . . . .

Chapter One

No 21 Henrietta Place

Mayfair, London, England

May 1811

Nothing of record ever happened in Henrietta Place.

Carriages did not collide. Servants did not quarrel in the mews. No one among the street’s jowly widowers remarried harlot second wives. No one tolerated stray dogs.

Families with spirited young boys boarded them in school at the earliest possible age.

A calm sort of orderliness prevailed on the street, gratifying residents and earning high praise from Londoners and country visitors alike. It was a domestic refuge. One of the last such sanctuaries in all of London.

Certainly, the stately townhome mansion at number twenty-one was a sanctuary to Lady Frances Stroud, Marchioness Frinfrock, who had been a proud and attentive resident since her marriage in 1768. With her own eyes, Lady Frinfrock had seen the degradation and disquiet that had become prevalent in so many London streets: noble-born men fraternizing with ballet dancers in The Strand; week-long ramblings in Pall Mall. And the spectacle that was Covent Garden? It wasn’t to be borne.

What a comfort, then, that Lady Frinfrock would always have Henrietta Place, where nothing of record ever happened. Where she could live out her final days in peace and tranquility.

“It looks to be fair for a second day, my lady,” said Miss Breedlowe, the marchioness’s nurse, crossing to the alcove window that overlooked the street.

“A fog will descend by luncheon,” said the marchioness, frowning.

“If it pleases you, we could take a short walk before then,” the nurse said. “To Cavendish Square and back? Spring weather is so unpredictable, we should take advantage of the sun before it disappears again for a month.”

“Cavendish Square is not to be tolerated,” said Lady Frinfrock.

Miss Breedlowe looked at her hands. “Only so far as the corner and back, then?”

“Not I,” said the marchioness, pained.

A sigh of disappointment followed, as it always did. How unhappily accustomed Lady Frinfrock had become to her nurse’s chronic sighing. It was obvious that Miss Breedlowe endeavored to be patient, although, in her ladyship’s view, not nearly patient enough. In return, the marchioness rarely endeavored to be agreeable enough.

And why should a woman of her age and station be prodded through an inane schedule of someone else’s design? To be forced to engage in robust activities intended for no other purpose than to move her bowels? If her inept solicitors felt that her alleged infirmity warranted the nurse-maiding of sullen, sigh-ridden Miss Breedlowe, then so be it. They could cajole her to compensate and house the woman, but they could not force her to abide her. Or to walk to Cavendish Square when she hadn’t the slightest desire to do so.

Miss Breedlowe cleared her throat. “Perhaps tomorrow, then.”

Lady Frinfrock made a dismissive sound. “If you wish to walk to Cavendish Square, Miss Breedlowe, pray, do not let my disinterest detain you.”

The nurse turned from the window and studied her. “I had hoped to discover an activity that we might enjoy together.”

“A vain hope, I fear. I am a solitary soul, as the tyrants at Blinklowe, Dinkle, and Tuft, would comprehend if their service to my estate extended beyond calculating my worth in shillings and pounds and subtracting their yearly portion. Instead they have shackled me to you.”

To her credit, the nurse did not blanch, but she also did not reply. The marchioness looked away. If such frank language could not elicit some measure of honesty from the woman, perhaps it would scare her into not speaking at all. Either would be preferable to her current trickle of disingenuous small talk, not to mention the incessant sighing.

“I dare say your planters are the most beautiful for several blocks, my lady,” Miss Breedlowe said after a moment. “Do you direct your gardener in their care?”

“They are not the loveliest on their own accord, of that you can be sure.”

“How talented you are.”

The marchioness snorted. “You can but see what becomes of a garden when left unattended, even for a week. Just look at the deplorable state of Lord Falcondale’s flower boxes and borders, if you can bear it. Such an eyesore.”

“Oh, yes. The new earl. Which house is it?”

“Number twenty-four. There. Directly across the street. It’s been in his family for an age.” She gently tapped the window with her cane. “His late uncle, the previous Lord Falcondale, paid fastidious attention to the upkeep of those planters. Tulips and ivy mostly, this time of year. Simple flowers, really. No effort to maintain, but perfectly lovely if kept headed and weeded, which he did. Not to mention his staff swept the steps and stoop several times a day, even in the damp. But now his far-flung nephew has inherited, and I fear the entire property will fall into disrepair.”

“Hmmm,” said Miss Breedlowe. “That would be a great shame.”

“Doubtless it seems like a small thing to you, but this sort of irresponsibility can bring about the demise of order and calm in a quiet street like our Henrietta Place. It doesn’t help that number twenty-two,” she gestured again, “next door to Falcondale’s, has been unoccupied and for sale these last five years. The house agents keep it up, but there’s no substitute for the loving care of a devoted owner and staff.”

“Indeed.”

“To make matters worse, the new earl is completely unresponsive to neighborly suggestion. I dispatched Samuel to speak to his gardener, only to be told that the man has let him go, the careless sod.”

“Dismissed his gardener?”

“He sacked the whole lot. I’ve since learned that every servant has been turned out. Now I ask you, how is a house of that size to be maintained without staff?”

“I can only guess, my lady, but do take care. It would not warrant you to become overset.” She ventured small steps toward the marchioness.

“The demise of order and calm.” Lady Frinfrock tsked, waving her away. “The demise of order and calm.”

As if on cue, a carriage, buffed to a sun-sparkling sheen, whipped around the corner, thundering down the cobblestones from the direction of Welbeck Street.

“Who the devil could this be?” the marchioness whispered. She drew so near to the window, her breath fogged the glass. The carriage careened toward them at a breakneck pace, slowing slightly as it neared Lady Frinfrock’s front window. With eyes wide, the marchioness watched it jostle past her house and well beyond the weed-ridden planters of Falcondale’s front door. Only when it reached the unoccupied house at number twenty-two did it lurch to a stop, the coachman yanking the reins as if his life depended on it.

“Such traffic in the street today,” Miss Breedlowe said.

“Nonsense.” Lady Frinfrock pinned her gaze on the carriage. “There is no traffic in Henrietta Place. Not on this day or any day. Such recklessness? A conveyance of this size? It’s wholly irregular!”

“Indeed. Perhaps a neighbor is expecting out-of-town guests?”

“No relation to the occupants of this street could afford a vehicle so grand,” she said. “Except, of course, for me. And I have no relatives.”

“Not even the new earl, Lord Falcondale?”

The marchioness harrumphed. “He cannot afford even a gardener.”

The carriage door sprang open, and Lady Frinfrock leaned in.

“Oh, look,” said Miss Breedlowe, cheerful interest in her voice. “It’s a young woman. How beautiful she is. And her gown. And hat. Oh, she’s brought someone with her. A companion. Hmm. Perhaps a servant?” Her voice went a little off, and she crooked her head to the side, studying the two women collecting in the street.

“Is that an African?” Lady Frinfrock nearly shouted, planting both gloved palms on the spotless glass of the window.

“I do believe her companion is an aboriginal woman of some sort,” Miss Breedlowe said, her voice croaking, as she moved herself closer to the glass.

“But whatever business could they have in Henrietta Place?”

Miss Breedlowe reached out a hand to steady her. “Do take care, my lady. Perhaps we should return to the comfort of the chairs.”

“I shall not be comfortable in chairs,” said the marchioness, swatting her away. “But has the young woman come alone?” She tapped a bony finger on the glass. “Where is her family? Her husband or parents?”

“Perhaps the men who have accompanied her are her—”

“Servants, clearly,” interrupted the marchioness. “Look, Miss Breedlowe. Trunk after trunk. Crates and baskets. Oh, God. They are conveying it to Cecil Panhearst’s old house. It’s been sealed like a tomb since 1804.”

“So they are. Perhaps you’re to have a second new neighbor.”

“A lone young woman and an African?” She placed her hand on the window with no mind to the smudged glass.

“Highly likely, I’d say. It would appear they are . . . Yes, they are unpacking.”

“Well, that cannot be,” Lady Frinfrock declared, shaking her head at the street. “I won’t stand for it. Not without knowing who she may be or where she came from. And why she is accompanied by an African.”

“Oh, do not worry.” Miss Breedlowe said. “The servants will learn her story soon enough. If she has any staff at all, they will talk with the other servants on the street.”

For the first time since the carriage arrived, the marchioness lifted her eyes from the window and turned to stare at the nurse.

“Why, what an excellent idea, Miss Breedlowe.” She raised her cane and jabbed it in the direction of the startled younger woman. “How resourceful you are. The servants will talk.” She raised one eyebrow. “They will learn her story soon enough.”

As Miss Breedlowe stared in disbelief, the marchioness scrunched her face and then swung the tip of her cane in the direction of door.

“Oh, no, my lady,” said Miss Breedlowe, backing away. “You cannot mean me.”

“Oh, yes, ’tis exactly what I mean. Finally, a suitable application for your indeterminate hovering and resigned sighs. We shall devise a reason for you to approach her, and you will discover her business in my street. It is our duty as mindful, responsible residents to know.”

“But I was speaking of the maids, my lady. The kitchen boys.”

“The maids are unreliable. The kitchen boys are inarticulate. You, however, are ideal for this sort of thing. Steel yourself, Miss Breedlowe. We cannot know what manner of objectionable thing she may say or do. Better fetch your gloves. And your hat.”

. . . . . .

Chapter Two

No 24 Henrietta Place

Later that same morning

Bored, tired, and cagey, Trevor Rheese, Earl of Falcondale, hunched over the chessboard, ignoring the game, and wanted.

Wanted privacy, wanted freedom, wanted out.

It was a sin to want—scripture was very clear on it: Thou shall not covet—but Trevor had been only loosely adherent to scripture in his life, and generally when it aligned with whatever his first inclination might be.

At the moment, he was inclined to want.

It was not broad, his list of wants. He did not wish for wealth or possessions, fame or prestige. Honestly, he did not even care about bloody respect. No, the things he wanted were trifling, bordering on humble. A scant duo of circumstances, nothing more.

Firstly, he wanted to go. To leave. To depart the sodden, sullen, perpetual chill that hung over the islands of Britain like a shroud and to arrive anywhere else in the world. Anywhere except, he was careful to add, the scab-like string of baking rocks known as the Grecian Isles. Even more than he wished to depart England, he wished never to return to the crumbling shores of the Ottoman Empire’s island paradise, ever again. Leaving Athens had been only temporary fix; his enemies would search for him in England next. True freedom, he knew, lay anywhere else.

After Trevor left England, his second burning desire was to be left alone.

Utterly, entirely, completely alone.

He didn’t want to mingle with people of his own class. He didn’t want to mingle with people of his own country. He didn’t want to mingle with people of any country.

He did not want a mistress or a wife or an heir—or even a bloody house cat.

Truth was, he didn’t even want to be earl, but his uncle had succumbed to lung fever before ever taking a wife. It had been his mother’s dying wish that, if it fell to him, he would make some effort toward the estate.

How ironic, then, that when Uncle Peter cocked up his toes the old goat had been neck-deep in debt. Trevor spent his first month as earl selling his uncle’s assets—the last of which (assuming he could find a buyer) was the Henrietta Place townhouse.

Not much longer, he hoped. Two weeks. Perhaps a month.

Until then?

Until then, he would keep a close watch over his shoulder and pass the time playing chess.

“You are forcing me to think, Joseph.” Trevor gazed at the chessboard, scrutinizing his defense. “Ah, moved the knight? Clever. Remind me not to leave you alone to strategize for longer than five minutes.”

“Who was at the kitchen door?” Joseph asked, smiling. “Cook?”

Trevor shook his head. “No, it was a boy from the market. The cook, I’m assured, has finally come to terms with the fact that he needn’t return, ever again, regardless of any fresh rage that might rise to the surface of his wounded pride.”

“You look for vermin in the market crate?”

The earl sat back. “I did actually, not that it’s any of your concern. I didn’t see you leaping up to receive it.” He slid his queen’s rook across the board. “I think you’re the laziest manservant ever to survive a house-wide sacking.”

“Oh, I’m a manservant now? As in a paid valet?” He smiled again.

“Right. I’ve spoken too soon. A valet would require a pension, holidays, an afternoon off.”

The boy laughed. “I’d claim a proper salary before I bothered with that.”

“Ah, yes. Now I remember why I can’t get rid of you. I don’t pay you.” He advanced his king’s pawn, angling for a kingside castle.

He was just about to tell the boy that he would take the first turn in the kitchen, when a noise split the air. A loud noise. Shrill. The sound of wood scraping against stone.

“What the devil was that?” Trevor’s head snapped back.

“Sounds like something’s split in two,” said the boy, wide-eyed.

“It’s coming from upstairs. The third floor—no, the second.” Trevor stared at the ceiling. “The empty second floor. Where there’s nothing left to split.” He shoved from his chair and crossed to the stairway, looking up.

He’d grown accustomed to this during his years in Greece—sounds, scrapes, things that went bump in the night. Barely a week went by without the sleep-robbing sound of an argument, the shrieks and clatter of a raucous party, or, perhaps loudest of all, the clunk-clunk-clunk of something heavy and stolen being dragged up the stairs.

But they were in Mayfair now. Unexpected, jolting noises were out of place. Likely, it was nothing—a rodent or a bird flying against a window—but the hairs on the back of Trevor’s neck still bristled. He frowned at the ceiling, straining to hear.

“Perhaps you missed one of the maids,” Joseph said, trailing him to the stairs. “When you sacked everyone.”

“We’ve been alone in this house for nearly a week, Joe. No one has been missed.”

An unsettling second sound screeched from above. Next, a bump.

“Bloody, bleeding bother,” Trevor said under his breath, climbing the stairs, while keeping his eyes on the landing. “What now?”

“I told you the house would be haunted,” Joseph said.

“Yes, and I told you I couldn’t think of a less likely dwelling for the supernatural. Ghosts, I’ve been told, seldom congregate in light-filled rooms, swept clean, and devoid of all furniture. Nowhere to hide.”

A new noise—this one, unmistakably human—wafted from above. A sigh. Followed by a whimper. And then laughter.

Brilliant. Someone was laughing on the second floor.

Someone female.

He paused and held out a hand. The boy stopped.

“Maybe this was the spirit’s home, before we stripped it,” Joseph whispered, “and now it’s cross because we carried away all its possessions.” He crept up another step.

“Yes, and how bitter it now sounds. Laughing in the . . . I believe it’s in the music room.” He shoved off the top step and walked lightly down the landing, poking his head into each room as he went.

The noises, now a clatter of footsteps and banging—Was someone opening a window?—were loud and most certainly coming from the music room. The fully enclosed music room. One of many rooms with no direct access to the outside. Because they were thirty bloody feet off the ground.

He swore, cursing this burden, the newest in the long line of burdens he’d encountered while settling his uncle’s estate. The sounds and ruckus had stopped, naturally, now that they had bothered to have a look, but he motioned for Joseph to stay behind him.

Moving deftly, he fell against the wall behind the door. He nudged his head around the jamb. He scanned the room.

Nothing.

Four walls. Dusty floorboards. No furniture, because they’d hauled it off to auction last week. Not even a footstool remained.

Slowly, he edged back. Had they imagined the entire thing?

A window was open, he saw, its drapes fluttering in the morning breeze. That was odd and suspicious.

He stepped toward it.

And collided squarely with a girl.

No, not a girl.

His scrambling fingers felt a fully formed woman, curved and supple. She stilled under his grip for half a second, feigning docility. He craned to get a look at her, and she darted to the right. He grunted and lunged, snatching her back.

They tangled—arms against elbows, her hair in his face, her hands swatting—until finally he clamped down. He jerked the two of them back behind the door, muzzled her mouth with his palm, and scanned the room again.

Still vacant.

She’d been standing behind this very door; it was why he hadn’t seen her before. He’d have lost his thumb for such carelessness in Greece.

“Joseph! It’s a woman. Doubtful she’s alone. Check every room in the house. Mind yourself.”

The boy appeared in the doorway, wide-eyed, and Trevor jerked his head. Joseph nodded and darted away.

Trevor checked the room again. It was empty and silent except for her muffled struggle and the drapes snapping in the breeze. Carefully, he loosened his hold to crane around and have a look at her.

Bad idea.

In one glance, the room blurred and blinked and then dissolved entirely away. His whole consciousness became a pair of alarmed green eyes staring back at him.

He stumbled backward a step, taking her with him, and bumped into the wall.

She had hair the color of honey. The struggle had pulled it from a complicated knot on the top of her head, and now it fanned over them both. He felt it against his cheek.

She was young, but how young? Twenty-four? Twenty-five? No older than that, certainly. Well cared for, too, with a creamy complexion and small nose, long lashes, smooth hands. She smelled like a florist’s cart. She looked him directly in the eye without a moment’s hesitation.

“If there are others,” he managed to say, “do not think of alerting them. Not. One. Word.”

She tried to speak, soft lips moving under his palm, but her words were muffled by his hand.

“A simple nod of the head will do,” he told her. “Are you alone?”

Instead of answering, she bit him. Not deeply, but hard enough to startle. His hand jerked, and she used the moment to yank her head to the side.

“If you please,” she said, breathing heavily, “you’re suffocating me. I’m not at all given to screaming. It is not necessary to—”

“Are. You. Alone?” he ground out, leaning over her.

“I’ve come with my maid,” she said to the wall.

What sort of intruder was accompanied by a maid?

“If you please,” she said, “you’re hurting my shoulder.”

“Where is she?” he demanded.

“Where is who?”

“The maid.”

“My maid is not dangerous. She’s barely five-feet tall and nearly sixty years old. And she is nowhere. She has gone back into my house.”

“Your house? How did she manage that? This is my house, or did you lose your way and break into the wrong one? Ow!”

Her boot made piercing contact with his instep. “Look,” she said, struggling, “clearly, there has been a misunderstanding, but you cannot possibly think that I can harm you; you’re twice my size. Please, sir!” She ground her sharp heel deeper into the side of his boot. “You really can let me go. When I am unrestrained, I absolutely can explain.”

Let her go? He looked down at his hands. His brain had been so preoccupied with her face that he had nearly forgotten about her body.

Nearly.

She felt warm and soft and alive. The fabric of her jacket was stiff, but he clearly felt contours. Firmness here, softness elsewhere. Dainty elbow, delicate wrists and fingers.

Reluctantly, he released her, his fingers skimming the expensive wool of her traveling suit as they took the long route to fall away.

“Thank you.” She gasped, stumbling out of his arms. She yanked down the hem of her jacket and whipped her hair over her shoulder.

“Who are you?” he demanded.

“I am Piety Grey,” she said, recovering enough to offer a dazzling smile. “Of New York City. Recently relocated to London. To Henrietta Place. I have bought the house next door.”

She stuck her hand out, like a man intending to shake.

He stared at it, not quite sure what to do. She quickly retracted it. “But perhaps you don’t shake hands upon first meeting in England.”

“Falcondale,” he replied, reaching out his hand. Her gloveless palm felt small and cool. It was, perhaps, the first time he acknowledged the quality of the palm of someone else’s hand. He shook.

“We do, actually, shake hands in England, although typically not . . . Well, I can’t really say. I’ve been away for quite some time, and even before I left, it was never my focus.”

“Falcondale?” she asked. “As in the earl? Lord Falcondale?” She flung her arms wide. “But I was led to believe you resided in your country home this time of year.”

“You were led to believe what?” His voice cracked.

“It was in the contract,” she said. “Surely you remember. The solicitors went back and forth in order to get the dates correct. My arrival in London was to be timed with your departure for the country.”

He stared at her blankly.

“It is me, your lordship,” she prompted. “The woman who will be renovating the house next door? What a pleasure to meet you! And on my very first day in London.”

While he struggled with that statement, she affected more smiling, solicitous head nodding, and hand clasping. All of it was a little too joyous and felicitous and delighting. Trevor took an uneasy step back.

“I suppose it is obvious that I have found the doors and the shared passage.” She gestured to the wall behind her. “I’m sorry I didn’t introduce myself first by way of your front door. I never would have stumbled to your side of the wall if I had realized what I had found. I thought it was a closet.”

“Closet?” he repeated.

“There,” she said, pointing again.

Trevor swiveled his gaze like a tourist, sightseeing in his own home. In a far corner, a small door stood ajar in the shadows. She crossed to the small door, explaining, “It appears exactly the same on my side. Like storage, no? I thought, how lucky for me, another closet. But it wasn’t. It was the passage.” She smiled at him. “Our passage.”

Our passage?

He gaped at her. “I’ve never seen that door before in my life.”

“Oh,” she said, and her smile went a little off. “Well, it’s inconsequential, really, compared to our larger agreement. By the time I vacate your house, it’ll be nailed up, tight as a tomb, and you may go on ignoring it.”

Trevor stared, trying to mince through confusion so deep, his ears had begun to ring.

“This little door,” she explained slowly, soothingly, “leads from your house,” she patted the plaster beside the door, “through a small, tunneled-out passageway to my new house. See? It goes back and forth, between the two homes. Of course the buildings share this wall, as most row houses do.”

He ran a hand through his hair, scrambling to keep up.

“The passage connects to a room in my new house. It’s an odd, unexplained sort of fluke in the masonry,” she continued. “Well, not a fluke, really, as someone, at some point, must have planned for it, and tunneled it out, and installed doors on both sides. But it’s hardly typical and largely unnecessary; however, in the case of my renovations—”

“Stop.” Trevor closed his eyes and pinched the bridge of his nose. “If you please, do stop. Miss . . . ?” He squinted at her. “What did you say you’re called?”

“Piety Grey.”

“Please, stop, Miss Grey. I grasp that there is a passage. This I can plainly see. However, the bit that bears repeating, if you please, was your mention of an ‘agreement.’ Or, ‘contract,’ was it?”

She opened her mouth to answer him and then closed it, eyeing him critically. He stared back, raising an eyebrow.

“The agreement,” she began pointedly, “stipulated in our—yours and mine—paid, binding contract.” She eyed him. “It grants me the right to temporarily board in your home while carpenters make crucial repairs next door.”

Oh, God.

Trevor said nothing—there was too much, perhaps, in that moment to say—and she finished, “I have paid you a fee to reside here in your house during the months you take up residence in your country estate.”

“A paid contract?” Trevor repeated hoarsely.

“But this was the most crucial piece, my lord. I cannot believe you have no memory of the fifty pounds I paid to let this house.”

Trevor gasped. “Fifty pounds? Surely you’re joking.”

“Surely you’re joking,” she laughed, but it was a strained, nervous sort of laugh, frantic and panicked. She began to pace.

“This . . . this was all finalized,” she said, “signed and sealed and notarized.” She gestured to the right and left. “My lawyers in New York, your solicitors here in London.” She stopped and turned to face him. “You cannot mean that you have no memory of it? The money? The payment’s been issued and gone for months. Even before I sailed from New York. I know we have only corresponded via solicitors until now.” Miss Grey pressed on. “But surely you cannot say that you don’t recall any of this. I have a document signed by your own hand . . .”

“Not by my hand.”

“But you agreed.”

“I agreed to nothing,” he said. “Even if it made sense, which it does not, I would never agree to lease out my home to a—” He ran his hand through his hair again. “To anyone. But especially not to—” He ended abruptly, overwhelmed suddenly by the urge to do as he had done in Greece and simply give the order, Get out. He walked to the small door instead and slammed it shut.

“Sorry,” he said, reaching for calm. “Let me begin again.” He looked at her. “Are you married, Miss Grey? Are we saying, Miss Grey, or Mrs. Grey?”

“It’s Miss.” She raised her chin.

“Of course,” he said. “Very well. What of your father, where is he?”

She blinked. After a long moment, she said, “My father is deceased.”

“Your guardian, then? Who looks after your affairs?”

“I, alone, have moved to London and purchased the house, sir. I am in control of my own affairs.”

Rather than grapple with that statement, Trevor found words for what he should have said from the very start. “Miss Grey,” he began, grabbing the back of his neck, “I am the new owner of this house. I have only just inherited it, the title, all of it. The previous earl, my uncle, has died. Some six weeks ago. Any arrangement you made would have been with him.”

Miss Piety Grey gasped. “Died? I’m so sorry for your loss, my lord.”

“Don’t be. Be sorry that you made a deal with a dead man.”

Another gasp. “I beg your pardon, I have a docume—”

“Look,” he interrupted, “I’m selling the house. As soon as possible. I’m not sure of the sum it will fetch, but, assuming my solicitor confirms the legality of your arrangement with the late earl, perhaps I can repay your family some part of it.”

“If I wanted to reverse the settlement,” she said, “which I do not, the money would go to me, not my family.”

“That makes no sense, but very well,” he said. “The repayment would go to you, but this house will be put up for sale next week. In the meantime, I live here. You cannot, you shall not, reside inside it. Legal, binding documents or no. It’s entirely out of the question.”

Miss Grey narrowed her eyes. “I see. Of course, I could not predict your uncle’s untimely death, but I do wonder why you were not informed of our arrangement when you inherited? The paperwork to finalize the settlement was, at least on my end, oppressive. Did your uncle leave you no will, no ledgers? Did he not speak of it?”

“We were not familiar,” Trevor said. “I am still sifting through his, er, ledgers. My first priority was to take stock and sell everything of value.”

Miss Piety Grey crossed her arms over her chest. “Sixty?” she said.

“I beg your pardon?”

“I am offering you ten pounds more. To honor the agreement I made with your uncle.”

“You’re mad,” he said. “Even if I could move out so that you could move in, which I have no intention of doing, you could enjoy an extended stay at one of London’s finest hotels for that sum. Why not book a proper suite of rooms in St. James and wait out the repairs?”

“No,” she said quickly—too quickly.

He studied her. “Why in God’s name not?”

She drew breath to answer but then looked away. She was revising, taking care with what she said. Everything else had come out in a veritable gush, but now, she edited. It was, perhaps, her most revealing tell. Revealing what, he couldn’t say, but he knew when someone was withholding. Or lying.

“If you please, Miss Grey?”

She glanced up and offered a grim smile. “A hotel would never do,” she said quietly, almost shakily. “My circumstances require that I set up house immediately. I must move in,” she said, ticking off the list of “musts” on her fingers, “hire a staff, buy furnishings, establish myself in the neighborhood.”

When she looked at him again, she was emphatic. “I cannot appear transient,” she said. “I am not transient.”

Before he could respond, Joseph trooped into the room. The boy glanced quickly at Trevor but stared at the young woman. “They’re empty,” the boy said, his voice cracking. “The other rooms.”

“Yes, Joe. She is alone,” Trevor said, turning to look out the window. “And, you’ll be relieved to learn she is neither ghost nor forgotten maid. She is . . .” He looked at her.

“Piety Grey,” she provided again, reviving her smile.

“This is my serving boy, Joseph.”

She nodded and turned her smile on defenseless, impressionable Joe. “But you must meet my maid,” she said, darting to the passage.

“Tiny!” She shouted the word through the doorway. “Do come and meet our new neighbors!”

No, we must not meet your maid, Trevor thought, even as the sound of frustrated effort rustled from the other side of the tiny half door.

From the mouth of the passage crawled a petite, middle-aged woman with brown skin. She was dressed in the plain uniform of a servant, except for the bright-orange turban securing her hair. Her expression registered somewhere between diligent retainer and perturbed relation. Before she spoke, she looked at Trevor squarely in the eye.

“Missy Pie,” she said, “all the house trunks are inside. They finished ten minutes ago and then invited themselves in, right through the front door. Wandering around like company. Swarmed the ground floor, looking for Lord-knows-what. If you don’t get them outside, they’ll break something or steal it. They’re thick as ants on your jewelry trunk right now.”

“Yes, of course,” said Piety Grey, looping her arm around Tiny’s and patting the top of her hand.

“Lord Falcondale,” she said, “this is my companion and maid, Tiny Baker. As you can see, I was not exaggerating about her harmlessness.”

To the maid, she said, “Tiny, the earl next door has died, and this is his nephew. The situation, I’m afraid, is not as we expected.”

The woman narrowed her eyes at the earl, studying him shrewdly, looking back and forth between him and her charge.

Miss Grey went on, “If you’ll excuse us, my lord, we hired hostlers in South Hampton, and they have agreed to help us with the unpacking. I’m afraid they are more accustomed to horses than people.”

She nodded to her maid and released her, and the woman ducked through the passage.

Piety went on, “Of course, we have yet to unload our personal trunks because we planned to reside here.” She looked around. “I traveled from New York with very few fixtures, but it appears what I brought might be useful here. Have you no furniture?”

“The house is empty by design,” he told her impatiently. “The furniture has been sold—and hopefully the house will soon follow. It is empty except the bare necessities for the boy and me.”

“Very well.” She scanned the room like someone of a mind to provision. He cleared his throat and stepped in front of her view.

Miss Grey snapped her gaze to his face and went on, “My English solicitor has been notified of my arrival, but I do not expect to meet him for a day or so. No one could venture a guess as to precisely how many weeks it would take us to reach London from New York.” She paused, rubbing two fingers back and forth over her brow. “In the meantime, please think over my offer of an additional ten pounds. I’d like to discuss it more.”

Before his next denial, she added, “In future, of course, I will apply to your front door. Please do forgive my intrusion here. You have been most kind.”

“Right.” Trevor mumbled the word even while he thought, No, no, no, and no.

Before he could say the words out loud, she smiled again, gave a small wave, and ducked into the passage to trundle through.

. . . . . .

Chapter Three

Piety Grey waited a full hour before she approached the earl with a revised offer.

It was, for Piety, an exercise in extreme restraint.

It was also time well spent. She dashed off letters to her solicitors, to the staffing agency that would supply maids and footmen and grooms, and to the builder she would hire to restore the house. All the while she allowed her brain to reorder the impression of the man next door, who would, it seemed, crush her dream.

No, she thought, not crush it. The man who would blockade her dream. It took considerable effort to suppress the surge of queasy anxiety that flooded her belly at the thought of falling weeks behind schedule, and she reverted to her original impression. He was a crusher of dreams.

Of course he was absolutely nothing like her lawyers in New York had led her to expect. He wasn’t old, for one, not even a little. Not old, not infirm, and most annoyingly, not absent.

He was strong enough to pounce on her and restrain her. If he wished, he could pick her up and carry her around, which certainly he did not wish. He wished to be rid of her; he made that perfectly clear. Rarely, in fact, had she met a man so steadfastly disinterested to the point of rudeness, and again, how lucky. Preoccupied men didn’t have time to make assumptions, correct or otherwise, about her unique circumstances, and better still, they didn’t have time to “improve” said circumstances by insinuating themselves into her affairs.

So what if he seemed a little unyielding? Piety could manage men who wanted nothing to do with her. It was men who wanted too much who became a problem.

And management is exactly what he would require. Luckily, she had planned for this. Well, if not exactly for this, she had forced herself to anticipate any manner of setbacks or false starts. She would discover some solution and make him see rather than accept defeat. God forbid, she turn back now.

It was in the spirit of this—not turning back—that she and Tiny clipped down her steps after one, long hour; strode to his front door; and knocked. Stridently.

“Hello again!” Her beaming smile greeted him when he opened the door.

The earl blinked. It was clear that he had not yet become accustomed to the sight of her.

“I was not sure if you lived alone,” she said tentatively, craning around him, “or if we would have the pleasure of meeting the countess?”

He narrowed his eyes. “There is no countess,” he said, stepping onto the stoop and slamming the door behind him. “Which is to say . . .”

And so it began. Piety watched him descend. Deny and descend.

She retreated to the first landing, giving him plenty of room. She smiled, she nodded, she forced herself to listen. He made valid points, strong points. He was sarcastic and ironic and wry.

“So let me be very clear,” he said, taking a step down to the landing, “in no way”—he stepped down again—“am I amenable to”—another step—“the so-called agreement that you had with my uncle, the previous earl.”

Clearly, he tried to crowd her, to intimidate. I’m a man. I’m tall, solid, broad-shouldered.

The aggressive display was unnecessary; she knew this much from being tackled by him. Now, he loomed. While the tackle had demonstrated his strength and agility, the looming invited her scrutiny of the little things.

His tan, for example. He as far too tan for a gentleman. His face and neck were as brown as the sailors on the ship that had conveyed her to England.

And his hair. It was thick and brown with hits of auburn. Lighter on top from the sun. Too short to be stylish, but long enough to curl. Long enough to flop.

He was not, she thought, unpleasant to look at. If not traditionally handsome, then certainly he was compelling in a weary-warrior-left-out-in-the-sun-too-long sort of way.

Piety wondered if he was a warrior.

Or if he was weary.

She wondered how he came to be so very tan.

He could be a reclusive, asthmatic father of eight for all she knew, but it appeared that he lived alone. It appeared there wasn’t even a staff. Only the boy, Joseph. If so, another stroke of good luck to counter all the bad.

“I have no plans to move out until the sale,” he said, oblivious to her scrutiny. He stepped down again. “You cannot move in. Not for an extra ten pounds. Not for any amount. Unless you intend to buy my house, too.”

Now he was one step above her, looking down.

She stared up, shading her eyes from the sun. “I’ve come with a new deal,” she said softly. He was so close. There was no need to shout.

“The answer will remain no.”

“But you haven’t even heard my offer.”

He sighed. “Make no mistake, Miss Grey. This house will be put up for sale next week. Prospective buyers will visit. House agents will tour. Creditors will appraise. None of this can happen, you understand, with you installed in a bedroom, or elsewhere—with you anywhere at all.”

She rose to the same step. “Forget the bit about me letting a room or moving in at all. Of course you are correct, it would be wildly inappropriate for me to share this house with you, and I understand how disinclined you are to accommodate me. Instead,” she stoked up her smile, “what I really want is use of the passage.”

“What?”

Piety worked to replenish her patience. “My house is rustic and out of date,” she explained, “but I can live there. I am not afraid of a little dust or damp.” Behind her, Tiny cleared her throat dramatically, making the sounds of strangled shock, but Piety ignored her.

“It’s not what I had planned,” she went on, “but it will do. What will not do, however, is the stairs.”

Trevor nodded. He swore. He turned away. She heard him mutter words to the wall: “I don’t want to know. I do not want to know.” He turned back. “What about the stairs?”

Piety shook her head with remorse. “Rotted through.” She gestured heavily. “Apparently, there was a leak, and the damage nearly crumbled the entire stairwell from the first floor to the next.”

“Why not use the servants’ stairs?”

“Fire,” she said simply. It was the truth. Unbelievable, but true. The situation required no embellishment.

“If there are no stairs,” he asked slowly, incredulously, “how did you find yourself on the second floor and able to make your way through the so-called passage and into my house?”

“Oh, there is scaffolding,” she said, waving a dismissive hand. “It will do for now, but it is tenuous at best.” She looked calmly down the street. “And it would never support the weight of carpenters.”

“Carpenters? What is your intention for carpenters?”

“What do you think? The will restore the house. They will access the upper floors by using your stairs, and our passage.”

“You intend to trail through my house with carpenters?”

“I cannot allow renovations on the upper floors to be postponed until a new staircase is put up. Workmen, supplies, furnishings, they all must be conveyed up. Every room must see improvement right away. Not to mention, I, myself, will be settling in. Unpacking. Bringing in tapestry, carpets, art. I’ll need access as well.”

He drew breath to tell her an obvious, No, but she rushed on. “My new offer is this: Lease me access to the passage and permission to slip in a back door of your house, up your stairs, and through the passage when I need to reach my upper floors. That is what I want.” She drew breath to finish. “It is a fraction of what I paid for, but essential to what I need.”

He hesitated only a fraction of a second. “No.”

Piety screamed internally but pressed on. “Did you hear the bit about the back door? We wouldn’t be traipsing through the main hall.”

“Absolutely no.”

She tried again. “You will find that I am perfectly willing to work around the business of your daily life. I’ll forestall access for the carpenters until any time you name. Myself as well. We’ll all stay away. An hour or two each day to get to the top, that’s all we’ll really need.”

“And what of my sale?” he said, leaning on the banister. “I’m advertising the house as vacant and available to buy. I ask you, Miss Grey, how will this arrangement appear? With your team of workmen trooping up and down the stairs? With you, dragging carpets through the kitchen door?

“Unbelievable,” he answered for her. “And strange. And gossip-inducing. Not to mention, it would emphasize the fact that the second floor conceals a giant hole in the masonry and a phantom closet.”

“It’s a passage.”

“It’s yet another problem that I must solve.”

“Yes, I see your point. What if I forestall the workmen for a time, and I restrict the use of the passage to myself alone? In the evenings? So I may settle into the upstairs. So I may unpack.”

“You coming and going is worse than the workmen.”

Piety raised one eyebrow. “I’m sorry, my lord, that you find me so unpleasant.”

“It is merely your proposal that I find offensive,” he said, running his hand through his hair and looking at the sky.

“Not a proposal, a settlement. Paid in full. For a fraction of what I may actually receive.”

“Paid in folly,” he countered, “if the payment even exists.”

“But my money is gone, just the same. As you will see.” She took a shallow breath. Her composure was slipping; her smile was barely in place. “Your lordship, please. You are making this unpleasant when it does not have to be.”

He narrowed his eyes, studying her. She felt his slow perusal of her face. For better or for worse, she let her smile slip and allowed some of her weariness to show. But would he see her resolve? Her determination or desperation?

She opened her mouth to say more, but he cut in, his voice low and even. “Have your solicitor be in touch.” He backed toward the door. “Mine will review the documents. Some concession may be made. I cannot imagine what, because there is no circumstance wherein I will become involved in sharing a hidden trap door with you or with your workmen. If so much as an insect from your property scurries into my music room . . .”

She was about to simply tell him about her mother. And the money. About her need to insinuate herself into this house and this street. Instead, she was cut off by footsteps, padding up behind them. Piety bit her tongue and turned around.

It was a woman, thin and straight-backed, her steps careful and tentative. She admitted herself through the front gate as if stepping into a morgue.

The earl groaned. “Good God, what now?”

“Good morning, my lord,” the woman said nervously, her voice soft with humility. “I apologize for disturbing you. My name is Miss Jocelyn Breedlowe, and my employer, the Marchioness Frinfrock, is your neighbor directly across the street.” She gestured weakly to the towering mansion behind her.

The earl looked at the property and waited.

Piety did the opposite. She smiled broadly and descended the steps to extend a hand.

“So pleased to meet you, Miss Breedlowe. I am Piety Grey, and this is my maid, Tiny.” The woman shook Piety’s hand awkwardly and glanced to Falcondale, unsure.

Piety continued, “We are from America.”

The other woman smiled cautiously, nodding.

“From New York City,” Piety went on, “but we have relocated here. To Henrietta Place.” She gestured broadly, indicating the street. “And I’ve bought the house next to the earl. Number twenty-two.”

“How do you do?” the new woman managed. “Are you . . . will you . . . Has your family had the privilege of meeting the earl?”

Piety considered this a moment and defaulted to honesty. “I have moved to London alone, Miss Breedlowe. My father was lost to pneumonia in the autumn of last year. My mother has started a new life with a new husband. And this,” she indicated the street again, “this is my new life.”

Miss Breedlowe made a strangled sound.

The earl appeared beside Piety, suddenly animated. “Miss Grey,” he told the startled Miss Breedlowe, “was just explaining that she and I may be required to work together. To work closely together. To see repairs made to a wall shared by our two properties.”

The older woman blinked. She stared at Piety and back at the earl. She looked over her shoulder at the house of her employer. She coughed.

Piety shot the earl a disgusted look and weighed her choices. Well, she could hardly leave it at that. He was trying to scare them both away. He insinuated an impending scandal where there need not be. Not if they were mindful. Not if a handful of influential people could be made to see.

Miss Breedlowe clasped her hands before her, clearly trying to understand. She repeated the earl’s last words. “Work together?”

“Would you believe that the stairs in my new home are sorely damaged?” Piety raised her eyebrows.

“I hope you do not mean unsafe?”

“Gravely unsafe, I’m afraid.” Piety confirmed her words, following with a quick rendition of the stairs and scaffolding and the rot.

“You know, my intention was to become acquainted with all of the neighbors—it’s why I’ve called upon the earl—and I should like to meet your marchioness as well. My situation is unconventional, to say the least, but it is not wrong-minded.” Piety slid a glance at the earl. “It is not bad.

“Do you think,” she continued, “that I might call on her ladyship and explain?”

“Well . . .” Miss Breedlowe seemed at a loss for words.

Piety forged on. “I haven’t had the time to order cards, so may I impose on you to implore her? I can call whenever it suits her, including, well, including right now.”

The other woman nodded and cleared her throat. “Might I suggest you wait for an invitation from her ladyship? Likely, she will wish to summon you.”

“Lovely, but this is even better.” Piety clapped her hands together. “I’ll wait for her summons. Thank you, Miss Breedlowe.”

The woman’s face turned red, and she nodded but then looked at the earl. “I beg your pardon, Lord Falcondale?” she asked.

“Yes?” he answered, although his tone said, please—no.

“Forgive me,” she continued, “but the purpose of my . . . that is, the reason I approached you and the young lady was to—” She cleared her throat. “Lady Frinfrock wishes to extend one or two neighborly suggestions regarding the care of your flower boxes.” The woman cringed. “If you would be so obliged.”

“My what?” He grabbed the back of his neck. “No. Wait. Do not answer that.”

“I never wished to intrude on your business with the young lady,” she said.

“I have absolutely no business with the young lady.” He glared at Piety. “But you may tell the marchioness that the flowers should be the least of her worries. Oh, and the planters are only going to get worse.”

With that, he turned and climbed the steps, entered the house, and slammed the heavy door behind him.

~ End of Excerpt ~

Order your copy of The Earl Next Door

→ As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. I also may use affiliate links elsewhere in my site.